|

|

|

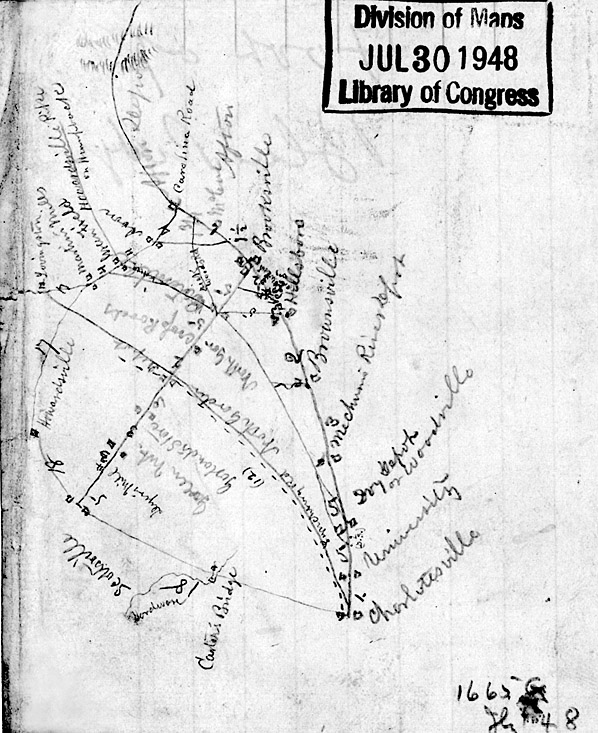

Name: The Yankees Ride Into Scottsville by Ruth Klippstein Date: March 6-10, 1865 Image Number: Burgess Photos 3_RollTwoNeg22A Comments: One fact both Northerners and Southerners could agree upon in early March 1865 was that "the roads were awful, and the weather exceedingly bad," as Judy Egberd of Charlottesville wrote to her daughter in Greensboro. With "no railroad communication now in any direction, and no mails from anywhere," she said she was sending this undated letter by a friend to Lynchburg for mailing (Mary Rawlings, "Sheridan's Raid Through Albemarle," Magazine of Albemarle County History, 1954). Her news was not about troop numbers, the campaign in Waynesboro, or other matters military. She reported what she was seeing in Charlottesville as Sheridan's Army of the Shenandoah spread out "in various places--this writer invited a colonel to stay in her house [on Park Street] and use the stables." After receiving a polite acceptance and "an elegant [visiting] card," she gratifyingly found that no other soldiers disturbed her. She wrote that public property had been stolen, "but no buildings were burnt in town; even the Depot was spared, because its destruction by fire would have endangered private property." (While the university buildings and military hospitals were passed over, damage was in fact done to warehouses and factories, a tannery, and several railroad bridges. Dr. Orianna Moon of Viewmont, who would later open a hospital with her husband in Scottsville, was a surgeon at Charlottesville's General Hospital.) Sheridan quartered himself at 522 Park Street, where "Miss Betsy Coles of the Enniscorthy family" was living; Merritt at 303 East High; Custer at The Farm, in the c. 1825 house there, in the southeast section of Charlottesville. The soldiers were scattered in the surrounding countryside, which consequently fared less well; "our country friends have suffered dreadfully. Corn meal, flour, hay, horses, and negroes were all in great demand." The Union came March 3rd; on Monday, the 6th, they marched south in three columns. In between these dates came mud, rain, and the raid in Scottsville. Sheridan divided his 3rd Cavalry into two large divisions, sending Major General Wesley Merritt and Brigadier General Thomas Devin directly south toward Scottsville, and Brevet General Custer with three divisions, Sheridan accompanying, southwest along the railroad and through North and South Garden almost to Amherst Court House. He sent a smaller troop toward Palmyra. The forces were to reunite after damaging as much useful infrastructure as possible March 8th at New Market (now Norwood) on the James River in nearby Nelson County. Devin and Merritt, aged 43 and 31 respectively ("the war at this stage was mostly a young man's effort," with Sheridan and Custer aged 34 and 26 respectively, according to Trices of Virginia by Robert H. Trice, quoting Nicholas) went south along the unsurfaced road, generally paralleling what we know as Route 20. There is still not major development along this road linking Albemarle County's past and current courthouse towns. In places, except for power lines and machine-rolled hay, the land might look as it did through the pouring rain that early spring. Scouts had given reports to Sheridan in Charlottesville; a map was not necessary. The shorter marches of this period of the campaign were in that way different from much of the war, when the absence of maps--North and South, commercial as well as military maps-led, as Richard Stephenson writes in Virginia in Maps, Four Centuries of Settlement, Growth, and Development, 2000, "to the spectacle of Northern--and Southern-generals fighting in their own country and not knowing where they were going or how to get there." Jedediah Hotchkiss, the Confederate's best topographical engineer and cartographer, a self-taught Staunton schoolteacher, produced his maps usually after drawing from horseback. Hotchkiss sketched the informal map, pictured here, in July 1865, emphasizing the relative ease of getting from Charlottesville to Scottsville and the James. "The Yankees marched in good order in spite of the heavy spring rains," writes Ervin L. Jordan, Jr. in Charlottesville and the University of Virginia in the Civil War, 1988.

The Hotchkiss map. Jedediah Hotchkiss, the Confederate's best topological

engineer and cartographer produced his maps after usually drawing from horseback. He shows the relative ease of getting from Charlottesville to

Scottsville and the James River. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress. Authoritative firsthand accounts of the following days in Scottsville are limited to U.S.--Northern--official records and reports, though family memories remain. We are fortunate that Richard L. Nicholas, who grew up "on a bluff looking at the James River in Buckingham"--directly across the river from Lock 22, where his ancestors at The Hermitage might have watched the marching and the burning in Scottsville unfold, and who went to Scottsville High School, has written the well-researched and useful Sheridan's James River Campaign of 1865 Through Central Virginia, 2012. Using the 1875 Green Peyton map of Albemarle, Nicholas shows a few properties on the way from Charlottesville to Scottsville: Hartman's Mill on Moore's Creek, a few places just under Southwest Mountain, and then T. Wingfield at Bellair, off to the right (or west) of the road. A large 1834 mill in that vicinity, Eolus, was not burned, due either to the heavy rain or to the successful intervention of a devoted miller. The men were moving toward the James River and Kanawha Canal, where there would be sufficient work to do. (K. Edward Lay, in Architecture of Jefferson County, 2000, notes that Union troops did burn the mill complex owned by William D. Meriwether at Moore's Creek near the Three Notch'd Road.) Four miles north of Scottsville, at George W. Dillard's c. 1810 Glendower--Dillard also owned the 1847 Chester, at 243 James River Road in Scottsville, which soon became a Union encampment--the soldiers took two horses, according to Dillard, after having been given the contents of his smokehouse and mill. At the close of the war, Dillard tried to get reparations as a Union sympathizer, to no avail. The Union troops arrived in Scottsville "the first time�from mid afternoon on Monday, March 6." They would leave March 7th and return the 9th and 10th. The official reports, Nicholas says, give "very limited information on Scottsville�. In fact, none of the reports specifically state that they spent a night in town." But the troops, bent on destruction, caused damage that Nicholas follows in the Land Tax assessments of Albemarle County for 1866; eleven lots in town had assessments lowered because of "injury by fire"--"a clear reference to destruction resulting from Sheridan's raid," Nicholas notes. The chief engineer of the James River Canal Co., Edward Lorraine, reported that besides two canal bridges, the company's shop, equipment, and stores such as beef and corn were all damaged; he says 26 houses were burned. Can we not assume that the initial wave of Sheridan's men, under Devin and Merritt, marching down Valley Street, would first have seen the still imposing three-story brick mill and later tobacco warehouse and 20th century braid factory, now the James River Brewery (571 Valley St.), built around 1836? It would have been spared destruction for its use as a Confederate hospital, thereby leaving one of Scottsville's notable structures untouched for its future development. Just north of that building was (and is) the 1800 brick two-and-a-half story building with a wood frame structure, a summer kitchen and slave quarters in its rear, near Mink Creek, possibly from 1790, according to the National Register of Historic Places registration form for Scottsville's Historic District. Since the mill wasn't burned, neither was this large house. What else still exists in Scottsville that the invading soldiers would have seen and evaluated? Across and south on Route 20, the two-story brick townhouse (now 510 Valley St.) from about 1832--to become Scottsville's apothecary in 1876 and much later the Sesame Seed natural food store--must have looked much as it does now. The Harris Building (474-476 Valley St.), c. 1840, housed Martha Harris's millinery and dry goods store and now Ward Realty. In the next block south, the Beal building (380-398 Valley Street), constructed from 1841 to 1850 as the Beal family's hardware and general merchandise store, showed both its stepped-back parapets, the south one now gone. The Griffin building (358-370 Valley Street), c. 1840, which "may have served as an inn during Scottsville's canal days," according to the 2010 Scottsville Museum's pamphlet entitled "Scottsville On the James, Town Guide and Walking Tour" (available at Baine's and at the Museum), still has its upper windows in their original locations, while the treatment of the facade now suggests the presence of two buildings rather than one. West, up at 145 Bird Street, the 1832 Presbyterian Church, with an exterior staircase to its slave gallery, was in place, though the Episcopal Church further west (410 Harrison St.) wasn't constructed until 1875. Some of our important commercial buildings date from the turn of the 20th century, after what Virginia Moore calls "the agony of Reconstruction." Many of those from the heyday of the Scottsville economic boom, however, Moore's "Golden Era," were there then, as now: c. 1840 Eagle Hotel--later the Carlton House (300 Valley St.) on the northwest corner of Valley and Main, long known as Bruce's Drug Store, now Balance Studio, was part of the Confederate hospital; an 1833 version of the Scottsville Methodist Church at 158 Main St., burned down in 1976; the 1846 Disciples of Christ Church (290 Main St.), now the Scottsville Museum, and the next door Barclay House (300 Main St.) from 1800-1838. Further down Main Street, on the north side, the Doll family house (380 Main St.) was probably constructed in the first decade of the 19th century, according to the "Town Guide and Walking Tour." The Tavern had greeted visitors and business people since around 1840. Across the street, one of the town's earliest structures, often called the Colonial Cottage and now called the Fore House (345 Main St.), was built around 1780, architectural expert K. Edward Lay concludes. Next to it, the Herndon House (347 Main St.) from the early 19th century would have also witnessed the passage of the troops. It is believed that Devin found quarters on March 9th up Old Drivers Hill to the north. Small domestic buildings such as these cottages and the Tompkins House, possibly constructed in 1780 at 180 Jackson Street, with its four corner chimneys, were not of interest to the Union soldiers unless they contained food. Near to them, however, the Canal Warehouse (225 South Street) and canal turning basin must have been. Again, by good fortune, the warehouse was not damaged-until the next flood--and instead left to await its rebirth as Scottsville continued to develop. Canal boats, as Nicholas writes, and their stores were destroyed. The foodstuffs they had been loaded with were hunted down in private homes, and Elias Mahoney's houseboat was burned. Returning to Harrison Street, the 1830 house we know as Old Hall (354 Harrison St.) was commandeered by General Merritt on the Union's return to Scottsville, on their way to Columbia. Custer housed himself at the 1835 house called Cliffside (300 Warren St.) with soldiers camped all over the lawns; that story was a centerpiece of the original Scottsville 1908 UDC women's narratives of their Civil War connections. Shadows (470 Harrison St.) "the only frame Greek Revival structure" in the downtown area, notes the "Scottsville Town Guide and Walking Tour." Built around 1825, it might well have housed a Union general but was spared. Homes further along were also marched past and not molested: 521 Harrison, built in the early 19th century and identified later as Dr. Reuben Lindsay's house; the Jefferies-Bruce House (540 Harrison St.), c. 1838, owned after the war by a Confederate army sergeant, a doctor-druggist, whose family later sold the house to Thomas Ellison Bruce, of Bruce's Drug Store. The 1842-1844 Tipton House, further along Harrison, is also on a high English basement, in Greek Revival style. There was next another fine brick house, later razed by the Scottsville Baptist Church (690 Harrison St.), and the church itself, first constructed in 1840. Finally, the Lewis House (240 Warren St.), now called Wynnewood, which was built in 1850 on the massive Lewis property; lower-ranking Union officers stayed there. While much of the spring of 1865 was rainy and foggy, with the rivers too high to cross and the citizens in "despair and misery" (Jordan), some of the March days the Union were in Scottsville were, at least as recorded by Jedediah Hotchkiss in his journal, "fine" while frosty, or raining only at night. The day the 3,000 Union troops moved out of Scottsville toward Richmond, left us the legend of Sheridan's cufflinks, given to the little girl on the street, who pointed, when asked by the General, in the correct direction--and, as the Scottsville Museum's web site says, leaving economic destruction that would take forty years to recover from--that day, March 10th, was, according to Hotchkiss, "a fine day."

First Image is Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, Burgess Roll Three; Photo by William Burgess |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum |

||||