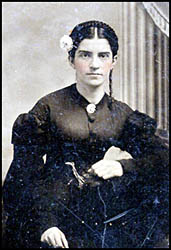

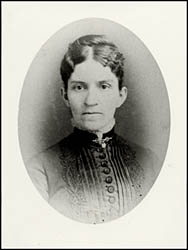

This is the story of a woman who lived in Scottsville 150 years ago. By modern standards she was quite provincial.

She was not beautiful, accomplished, or well traveled, but her life was anything but ordinary. She

lived in a time of national crisis, and she and her family were caught up in the tragedy that rent

the nation. She watched her husband and brothers march off to war and at war's end found

herself a widow with three small children. Further misfortunes were to follow. Tragedy

is so common in the simple annals of the poor that this story would scarcely merit our attention

were it not for the character of Mollie Harris, herself. She possessed unusual resilience and met

adversity with a courage and fortitude that enabled her and her family not only to survive the

hardships of their lives but also to triumph over them.

This is the story of a woman who lived in Scottsville 150 years ago. By modern standards she was quite provincial.

She was not beautiful, accomplished, or well traveled, but her life was anything but ordinary. She

lived in a time of national crisis, and she and her family were caught up in the tragedy that rent

the nation. She watched her husband and brothers march off to war and at war's end found

herself a widow with three small children. Further misfortunes were to follow. Tragedy

is so common in the simple annals of the poor that this story would scarcely merit our attention

were it not for the character of Mollie Harris, herself. She possessed unusual resilience and met

adversity with a courage and fortitude that enabled her and her family not only to survive the

hardships of their lives but also to triumph over them.

We know a great deal about Mollie and her family through a rich collection of primary sources.

Three of her children wrote reminiscences of their life in Scottsville between 1860 and 1888.

Furthermore, Mollie preserved 14 letters her husband wrote from the trenches during the siege of

Petersburg. These letters paint a vivid picture of life in the Confederate Army toward the end

of the war and give us a glimpse into the couple's relationship. These documents, along with

additional letters from family and friends, are displayed in the Museum as part of the "Whispers

from the Past" exhibit.

Mollie moved to Scottsville in 1837 when her father, Miletus B. Harris, decided to sell the family

farm in Louisa County and seek his fortune in Ohio. Accompanying him in the covered wagon were

his young wife Caroline, 4-year-old Tommy, 6-month-old Mary Susan (Mollie) and two servants who were

probably slaves, Edmund Hedgeman and Lavinia, better known to the children in later years as "Uncle

Ned" and "Aunt Binney."

One October evening the family drove into Scottsville and stopped on Main Street at Mr. Newman's store,

which had accommodations for travelers as well as goods for sale. The Harrises liked what they

saw and decided to settle in Scottsville. Miletus bought the store from Newman and established

the Harris Merchandise Company, which was to continue in business for over 70 years. The building

still stands, and fragments of the painted words, "Harris Mdse," are still visible on the brick walls.

The family prospered. In a few years they had accumulated enough money to buy a comfortable

brick house on Harrison Street. Miletus became a pillar of the local church and Superintendent

of the Sunday school. Three more boys were born to the family, John, Henry and Charles, all

named for Methodist ministers.

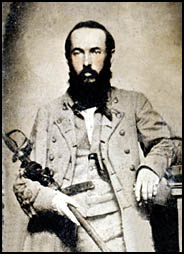

As his business grew, Miletus hired young men to clerk in his store, and they sometimes lodged

with the family. One young clerk, David Patteson of nearby Buckingham County, caught the eye

of 20-year-old Mollie and romance ensued, a development that must have caused Miletus to question

the wisdom of lodging young clerks under the same roof as unmarried daughters. In 1857, the

couple married and moved in with Miletus and Caroline. Their first child, Frances Evalina

(Fannie), was born in May of 1860.

These were turbulent times in Virginia. Factional politics threatened to split the nation,

and shortly after Lincoln's election in the autumn of 1860, South Carolina seceded, quickly followed

by six more states. In April 1861 Virginia followed suit and Richmond was named the Confederate

capitol.

The country was at war and Scottsville was quick to answer the call to arms. A company of

volunteers calling themselves "The Scottsville Guard," was soon raised, and after drilling for a

few weeks marched off to Manassas amid an outpouring of grief. After the Guard left, an effort

was made to raise another company, and James C. Hill, a local businessman, organized the Scottsville

Grays in early May and was elected its Captain. David Patteson enlisted in the company as a

private. After drilling three weeks the Grays marched away to catch the train for Lewisburg.

Although the departure of the Guard had accustomed the town to the idea of war and family separation,

Mollie, holding her one year old daughter in her arms and pregnant with her second child, must have

watched her husband's departure with a mixture of pride and apprehension.

The country was at war and Scottsville was quick to answer the call to arms. A company of

volunteers calling themselves "The Scottsville Guard," was soon raised, and after drilling for a

few weeks marched off to Manassas amid an outpouring of grief. After the Guard left, an effort

was made to raise another company, and James C. Hill, a local businessman, organized the Scottsville

Grays in early May and was elected its Captain. David Patteson enlisted in the company as a

private. After drilling three weeks the Grays marched away to catch the train for Lewisburg.

Although the departure of the Guard had accustomed the town to the idea of war and family separation,

Mollie, holding her one year old daughter in her arms and pregnant with her second child, must have

watched her husband's departure with a mixture of pride and apprehension.

The Confederacy was at a considerable disadvantage. The South had less population than the

North and little industry. The export of cotton, the primary cash crop, was reduced to nil by

the Union blockade. But none of this mattered to the men of the Scottsville Grays, the Border

Guards, the Jackson Avengers and the Pigg River Invincibles who made up the 46th Virginia Infantry.

Everyone knew that a Southerner was worth a dozen Yankees, and the war would be over in a few weeks.

As the weeks lengthened into months and the months into years, the 46th Virginia, now part of the

Wise Legion, languished in obscurity. While Lee fought epic battles and the Army of Northern

Virginia covered itself in glory, Wise's Brigade marked time for two years, first on the Virginia

peninsula and then in Charleston, SC. With little action and few casualties the 46th Virginia

became known as "The Life Insurance Company." All that was about to change. In May 1864,

the brigade received urgent orders to return to Virginia. The Union Army had landed fifteen

miles from Richmond and General Lee needed every available man to defend the capitol.

With most of its young men in the army, Scottsville's thoughts must have centered on the war.

Three of Mollie's brothers had joined the army as had David's. Mollie and the children saw David

infrequently, but when his father died, he received a 25-day furlough from South Carolina to visit

his widowed mother in nearby Buckingham County. David proved a good soldier. In the

volunteer forces of the time company officers were elected rather than appointed, and in July 1862

David was elected 3rd lieutenant, making him the junior officer of the Grays.

David's collected letters to Mollie begin on March 28, 1864, a month before the Grays were ordered

to Petersburg and continue until March 24, 1865, five days before he was mortally wounded in the

opening battle of the Appomattox Campaign. They make interesting reading. Much of the

content is predictable: the misery of life in the trenches, concern about the welfare of his

family in Scottsville, the names of casualties and deserters and the petty details of everyday life.

However, other themes develop over the course of the year: David's growing realization that the

Confederacy is disintegrating, his resolve in the midst of adversity, and his steadfast devotion to

Mollie.

The winter of 1864-65 was unusually severe, and life in the trenches was wretched. A soldier

from a North Carolina regiment summed up his unit's experience in Petersburg this way: "It lived in

the ground, walked in wet ditches, ate its cold rations in ditches, slept in dirt covered pits."

On December 18, David sent Mollie the following poem as a Christmas present:

| I think of thee at twilight dear, |

| When blessed day is gone. |

| I think of thee at midnight dear; |

| I think of thee at dawn. |

| |

| I think of thee in rainy weather, |

| Although it does me drenches. |

| I think of thee in rifle pits, |

| And also in the trenches. |

| |

| I think of Fannie, 'dearest girl,' |

| I think of Willie's squall; |

| I think of Maggie and the babe, |

| I think, I think of all. |

| |

| I think of home and all its sweets, |

| Would like to be there, too; |

| But while the foe doth me confront, |

| I know that will not do. |

| |

| So be content and let us wait |

| A few more years at best; |

| Until we whip old Grant, old Meade, |

| And old Butler, the "Beast." |

| |

| And in conclusion, let me say, |

| I have eat up all my meal; |

| So by the boat, when Captain comes, |

| Send on that Christmas veal. |

As the siege of Petersburg wore on, things turned increasingly grim. On Dec 27, David wrote,

"I hope you are having a nice Xmas, I don't say merry, because I don't think this is a time for

merriment. The clouds that hang around us at present are dark and threatening. Hood's

great defeat in Tennessee & Sherman's advance into Georgia, taken into consideration with other

things . . . has caused a gloom to come over me that I find hard to discard." Desertions

from the company increased and David often included news about local boys who had run off only to

be caught and returned to the unit. In one such case, Richard Beasley, after deserting the

Grays in 1863 and voluntarily returning in 1865, was sentenced by Court-martial to seven months in

the trenches. As everyone else in the Grays was in the trenches already, it would seem that

the court, in this case, was lenient indeed.

In March 1865, the war came to Scottsville when General Sheridan led 10,000 Union troops into

town to destroy the canal locks. In addition to destroying the locks, they burned homes and

businesses and stole from private citizens. When the Columbian Hotel on Main Street caught

fire it spread to the entire lower end of town, and Miletus came close to losing the store.

As neighboring buildings blazed around them, he and Charles struggled to beat back the flames.

At this critical moment Sheridan, himself rode by and ordered the marauding troops to leave the

old man and boy alone.

The siege of Petersburg had lasted nine months. Having failed to break through the

Confederate lines, Grant now attempted to out flank them. His first objective was

destruction of the South Side Railroad, one of Lee's lines of communication with North Carolina.

To block this thrust Lee sent Johnson's Division, including the 46th Virginia, from its position in

the trenches of Petersburg, to the Boydton Plank Road at Hatcher's Run, ten miles southwest of the

city. David's last letter to Mollie is written from this location.

The letter is a disconcerting one, made more poignant by our knowledge that its author has only

a short time to live. David jumps from subject to subject, and his accompanying changes in

mood, moving from despair to resignation, bespeak his troubled mind. His mother is dying, and

he has failed to obtain a furlough. The Army has begun to unravel. ". . . our men are fast

deserting, even the regiments are mere skeletons . . ." However, David's resolve is

undiminished. " . . . I have dedicated myself to the cause long ago - believing religiously

that it was my duty to do so, so 'sink or swim' I am with it; it is a great deprivation to be away

from you and the children, am afraid too that you will tire under so long and protracted a struggle

as this has been, . . . and being surrounded by financial, mental, and bodily battles, give way

under the weight."

On March 29th, General Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain attacked Wise's Brigade at the Lewis Farm

where they were guarding the Boydton Plank Road. Chamberlain forced the Virginians back

about a mile, but when he halted so supporting troops could catch up, Wise unleashed a fierce

counterattack. Just as he was about to destroy Chamberlain's force, a Union battery of

four cannons, quickly maneuvered into position beside the Lewis farmhouse, opened up upon the

Confederates with canister, a lethal scattershot projectile that acted like a very large sawed-off

shotgun. With artillery support and the infusion of fresh reinforcements, Chamberlain was

able to stall the Confederate advance, and he and Wise both retired from the field.

During this battle a projectile, probably a minie ball, struck David in the left hip, breaking

his femur. He was captured and sent to a field hospital near Grant's headquarters at City

Point, now known as Hopewell. From there he was sent to Armory Square Hospital on the

Washington Mall, where the National Air and Space Museum stands today.

Constructed in 1862, the 1,000-bed Armory Square Hospital complex spread across the mall and

included twelve well-ventilated pavilions, service facilities and a chapel, making it one of the

largest Civil War hospitals in the area. The care was excellent. Most of the nurses were

men - Walt Whitman being a famous example - but in 1862 women joined to nurse the sick and wounded.

Amputation was the most common procedure performed by Civil War surgeons. Projectiles like the

minie ball were heavy and slow moving and often shattered bone. With the high rate of infection

and primitive orthopedic procedures available, amputation offered the best chance of survival.

If done within the first 24 hours of wounding the survival rate was 75%; after 24 hours it fell to 50%.

David's surgery, described only as a critical but rarely successful operation, must have been a high

above the knee amputation. Weakened by blood loss, infection, a long journey and a delay of

more than a week, David was a poor candidate for surgery, and during the procedure he hemorrhaged and

died on April 7th. He was 31.

Amputation was the most common procedure performed by Civil War surgeons. Projectiles like the

minie ball were heavy and slow moving and often shattered bone. With the high rate of infection

and primitive orthopedic procedures available, amputation offered the best chance of survival.

If done within the first 24 hours of wounding the survival rate was 75%; after 24 hours it fell to 50%.

David's surgery, described only as a critical but rarely successful operation, must have been a high

above the knee amputation. Weakened by blood loss, infection, a long journey and a delay of

more than a week, David was a poor candidate for surgery, and during the procedure he hemorrhaged and

died on April 7th. He was 31.

News of David's death was delayed, and soon after he disappeared from the battlefield Mollie went to

look for him, a journey that must have required unusual courage in those chaotic times. A

dispatch about his death had been sent from Washington on April 7th, but was misrouted and lost.

Mollie traveled to Grant's headquarters at City Point and went straight to the General's tent where

she was received with the greatest courtesy. Grant said he would do everything in his power to

get information about her wounded husband. A few days later she received word that he was a

patient in Armory Square Hospital. Mollie returned home to Scottsville in early May, still

ignorant of David's death, and wrote the following letter to her brother Henry, then a prisoner of

war in Boston harbor. "Mr. Patteson is wounded and a prisoner at Washington. I have just

returned from City Point where I have been in search of him. I have reason to hope his wound is

not too severe. I put in an application for his parole which General Ord forwarded approved

consequently hope soon to have him at home." At the end of May the family received a letter

from Petersburg relaying news of David's death and giving the details of the lost dispatch.

News of David's death was delayed, and soon after he disappeared from the battlefield Mollie went to

look for him, a journey that must have required unusual courage in those chaotic times. A

dispatch about his death had been sent from Washington on April 7th, but was misrouted and lost.

Mollie traveled to Grant's headquarters at City Point and went straight to the General's tent where

she was received with the greatest courtesy. Grant said he would do everything in his power to

get information about her wounded husband. A few days later she received word that he was a

patient in Armory Square Hospital. Mollie returned home to Scottsville in early May, still

ignorant of David's death, and wrote the following letter to her brother Henry, then a prisoner of

war in Boston harbor. "Mr. Patteson is wounded and a prisoner at Washington. I have just

returned from City Point where I have been in search of him. I have reason to hope his wound is

not too severe. I put in an application for his parole which General Ord forwarded approved

consequently hope soon to have him at home." At the end of May the family received a letter

from Petersburg relaying news of David's death and giving the details of the lost dispatch.

Although the war was over reconstruction was a dark time for Scottsville. The canal lay in

ruins and much of the town was burned. Stagnant business and inflation impoverished the citizens.

The Confederate money David had sent in his letters was now worthless, and Mollie had to teach school

to make ends meet. Fortunately, neither the house nor the store was destroyed, and Mollie and

the children were able to move in with Miletus and Caroline. Many freed slaves left town, but

Aunt Binnie and Uncle Ned chose to remain in their little cabin at the edge of the Harris property,

and helped raise the little Pattesons just as they had the young Harrises.

Mollie was neither beautiful nor wealthy, and with three small children, she seems an unlikely

target for young men with romantic designs. However, she was intelligent and vivacious and did

not lack for suitors. George Whitehead, a young man who proposed to Mollie and was turned down,

wrote her several letters expressing bitter disappointment at his rejection. The Victorian Age

was more given to hyperbole than our own, but even in that flowery age the chronicle of George's

"blasted hopes and destroyed happiness" must have broken new ground. His letters abound in

passages such as the following: "Oh Pattie, the road that destiny requires me to travel is

overgrown with 'thorns and thistles' and is overshadowed with a deeper and darker gloom than the

blackness of darkness. I travel this gloomy pathway alone." Happily, George did not die

of a broken heart as he had feared, but recovered to become a Virginia state senator.

The suit of Richard Allen Hill, Major Hill's younger brother, proved more successful. Allen

fought at 1st Manassas and Seven Pines in the Scottsville Guard, and in 1862 enlisted in the Grays.

He was elected First Sergeant of the company, making him its senior noncommissioned officer.

Like his older brother, Allen was an amputee, having lost his left hand to a sniper who had caught

him scratching his head. In December 1869, Mollie married Allen in the Methodist Church, and

after a brief honeymoon, the family moved into rooms on the second floor of Miletus' store.

These rooms were the site of the family's next adventure.

In 1870, Scottsville experienced a flood of unprecedented violence. Boats were smashed,

livestock drowned and 20 houses washed away. By the time the crest of the flood reached

Scottsville, around midnight of September 30, water had begun to trickle into Mollie's second floor

bedroom where she lay in labor with the couple's first child. Dr. Reuben Lindsay, the family's

physician, was in attendance, having made his rounds by rowboat instead of on horseback. As the

water rose higher in the room, he turned to Mollie's anxious husband saying, "Allen, dog-gone

it, we've got to get Mollie out of here, quick!" John Hill, the unborn child in question, wrote

a delightful account of what happened next: " . . . Father took Dr. Lindsay's rowboat and

hunted up Alex Napier, the ferryman. Fortunately, one of his flatboats, used for ferrying

teams across the river, had been saved and was tied to the shore not far from our house. Napier

poled his boat right up the middle of Main Street, in about ten or twelve feet of water, and tied up

just under the window of Mother's room. It was a simple matter to remove the window sashes,

and take her out, mattress and all, along with the doctor and nurse. Alex Napier, with Father's

help, poled the boat across to dry ground, landing. . . at the rear of the Methodist Church.

And now, as the boat touched the shore, the stage being properly set for something out of the ordinary,

I was born!" Because of the circumstances of his birth, John Hill was thereafter known as "Noah"

to the people of the town.

Allen had no profession, and having lost his left hand, found it hard to make a living.

He worked at a number of jobs including packet boat captain, town sergeant and print shop assistant.

He and Mollie even tried running the Carleton House, a small hotel on Valley Street. Although

they were not well to do, they managed to get by, but now their luck changed and tragedy struck the

family again.

Childhood mortality was much higher at the end of the 19th century than it is at present, and it

was not uncommon for a family to lose one or more children. In 1872 Allen and Mollie had a

second child, a little girl whom they named Mary Allen Hill. Mary lived only four days and was

buried in Maryland where the family was living temporarily. In 1875 a third child was born to

the couple and named Charles, after Mollie's brother Charles B. Harris. Charles was strong and

healthy, but when he was two years old he fell from the arms of his nurse, Bob Lewis, and died a

short time afterwards, probably from intracranial hemorrhage. Allen and Mollie must have been

devastated.

A final child was born in 1880 and named Henry Harris, after another of Mollie's brothers.

After the death of Mary and Charles, Mollie found great joy in her new baby and must have considered

him a special child. Happily, he did survive, though not without incident. We are

indebted to his brother John ("Noah") for the following anecdote: "For a while, it looked like

Harry was safely launched on 'the straight and narrow way,' but one day I found him standing on the

old horse-block in front of Harris Bros. Store, surrounded by a group of laughing boys, and cussin'

like a sailor. I think I have never heard more artistic swearing, not even . . . in the West

where cussing has been reduced to a science. Investigating, I found out that (some of the boys)

had been deliberately teaching him to cuss, and Harry had proved an apt scholar." An even more

embarrassing episode occurred during Harry's christening. When sprinkled by Pastor Crider he

blurted out, "Damn you, stop pouring water on my head!" Mollie was mortified and, taking

definitive action, she washed out his mouth with soap, a remedy that must have been effective,

because Harry never uttered another curse word and later became an elder in the Presbyterian Church.

Scottsville's economy was tied to the canal, and when the railroad came to town in 1881, canal use

plummeted and the town suffered economic decline. Allen found he had to go further afield to

get work and there were few job opportunities for the older children. In 1888, the family sold

the old house and moved to the Roanoke-Vinton area. Will started a newspaper in Vinton and

John and Fannie both got jobs. Harry, the apt scholar of cursing, proved equally adept in the

classroom, and after graduating from VPI became a professor of Chemistry. Shortly after the

family moved to Roanoke Mollie received a telegram saying that Aunt Binney was dying and wanted to

see her. She took the midnight train and arrived in Scottsville the next morning. John

wrote, "Going straight to her cabin, Mother knelt down by the bed and took the dear old soul in her

arms. Aunt Binney, with hardly enough strength left to speak above a whisper, said: 'Miss

Mollie, I just couldn't die till I'd seen you!' and those were her last words. She died,

literally in my Mother's arms."

Allen died of a stroke in 1902, while visiting relatives in New Kent County, but Mollie lived

quietly in Roanoke until 1909 when she died of pneumonia at age 72. Following the custom of

the time, Mollie's obituaries dealt at length with her Christian virtues, but failed to capture the

essence of her character or her influence on those who knew her. Without the letters she

carefully preserved and the written accounts of her children, we would know nothing more of Mollie's

rich and eventful life than the newspaper's empty summary: "She was a widow lady, but had been twice

married." Miss Willie Hickcock, a stern schoolteacher and one of Scottsville's most colorful

characters, gave a more fitting tribute. In a letter to John she wrote, "Your mother was my

first friend; I loved her better, far better, than I have loved any other friend, the few kin I have

not excepted."