|

|

| |

by Richard L. Nicholas | |

|

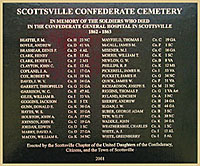

A central granite obelisk in the cemetery has inscriptions on three sides. Colonel Henry Gantt and Major James Christian Hill were prominent citizens in Scottsville's history. Gantt, a native of Scottsville and a graduate of V.M.I., was the commander of the 19th Virginia Infantry Regiment, the vast majority of which hailed from Albemarle and Charlottesville. Hill, also a resident of Scottsville and later a legislator, was a Major in the 46th Virginia. But there has always been an enigma concerning the names of the unknown soldiers represented by the headstones. Although the Scottsville Chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy has faithfully maintained the site since 1908, little was known about the history of the cemetery or the hospitals, and none of the soldiers buried there had ever been identified. The persevering ladies never gave up hope, however, and with their encouragement a diligent effort was made to find some answers to these questions. At the beginning of the Civil War, the Confederacy established a number of hospitals in Richmond and other larger and more accessible urban areas such as Lynchburg and Charlottesville. But as the war progressed and casualties mounted, the need for more hospitals escalated, and numerous smaller medical facilities were dispersed throughout Virginia in more remote communities like Scottsville, Palmyra, and Farmville. The selection of Scottsville as a site for a hospital was influenced by the availability of the James River and Kanawha Canal for transportation of the sick and wounded from Richmond, a plentiful water supply in what was considered a healthy environment, and the fact that several buildings existed which could be converted into hospital use. So in June of 1862, over a year after the beginning of the war, the General Hospital at Scottsville opened.

Previous descriptions of the Scottsville Confederate Hospital have all referred to the singular Baptist Church building located on Harrison Street on the hill overlooking Valley Street. Note, however, that the monument inscription refers to the plural Hospitals. In reality the hospital consisted of three existing buildings in town that had been converted to hospital use, as well as a fourth building which was erected just outside of town.

The third building in town which served as a hospital was the Scottsville Baptist Church on Harrison Street. In 1863 it was described as a 40' by 40' brick building which was converted into one large ward with a second floor gallery. The building was impressed from the congregation at a rent of either $12 or $35 per month. It had room for only 20 patients. A fourth hospital structure was built by local citizens on a hill about a half mile from town. It was a small frame house which accommodated 24 men and was used exclusively for smallpox patients. The site of this building has not been found. The Surgeon in charge of the Scottsville Hospital was Dr. James M. Jefferies, who was paid the princely sum of $160 per month. Jefferies lived in the large brick house on Harrison Street that was subsequently acquired by the Bruce family in 1919, and now owned by Jeffrey D. Plank. Other doctors assigned to the hospital at various times included Powhatan Bledsoe, James Fife Hughes, and Edward C. Mayo. Interestingly, all four physicians associated with the hospital attended the University of Virginia. Although the hospital was open from June 1862 through September 1863, records are available for only 10 months of that period. Information for the other five months of operation are missing. During those 10 months a total of 746 men were admitted and 2236 men were treated in the hospital. Unfortunately for historians, the only names listed are the 41 men who died during that time, and another four who were identified as being wounded, and were subsequently discharged from the Army. During the first summer of operation, July through September 1862 proved to be the period of peak activity for the hospital. During that three-month interval, 773 men were treated in Scottsville. In an amazing feat of endurance, Dr. Jefferies somehow managed to survive these three months as the facility's only physician. Fortunately for Jefferies' health, other doctors soon arrived to take some of the load off his shoulders. By that winter, the number of monthly admissions to the hospital dropped off dramatically from a peak of 220 in September to only 30 in January 1863. However, the hospital remained a busy place as the number of men treated declined much more slowly from 344 in September 1862 to 121 a year later. With the opening of the hospital, so inevitably came deaths. Within a month after admitting the first patient, 12 men had died from a variety of causes. In all, a total of 41 men are named in the 10 monthly records as having died in the Scottsville hospitals. The dead men came from seven states of the Confederacy: Georgia 13, North Carolina and Virginia 7 each, Alabama 6, South Carolina 5, Mississippi 2, and Texas 1. The deaths naturally caused the community to search for an appropriate burial site. Mary Elizabeth Moore, the owner of the factory building which was being used as a hospital, also owned extensive nearby property. She apparently solved the burial site problem by contributing a plot of ground for a cemetery a few hundred feet up the hill from the factory building. There, at the north end of Moon Street, the dead soldiers were laid to rest in graves which were unmarked and neglected for the next 45 years. Finally, in 1908 the local chapter of the United Confederate Veterans called attention to the neglect of the graveyard, and attempted to solicit funds to restore and mark the graves, and erect a suitable monument. About the same time, Miss Hannah Moore, the daughter of Mary Elizabeth Moore, informally donated the property to the United Daughters of the Confederacy. Dr. L.R. Stinson eventually acquired ownership of the cemetery and in 1929 legally conveyed "Moore's Hill Confederate Cemetery" to the Scottsville Chapter of the U.D.C. The aging and dwindling Confederate Veterans were unable to raise funds to erect a monument or to restore the cemetery, and so the entire project was turned over to the U.D.C. They put up an iron fence in 1909, and dedicated the monument in 1914. There is no record of the origin of the 40 individual headstones, but in all likelihood they were also erected at the same time as the monument. In addition to the questions about the identity of men buried in the cemetery, there is also controversy about the number. The discrepancy between the 40 headstones and the total of 41 deaths recorded in the hospitals can be accounted for by the fact that the body of a Georgia soldier is known to have been sent home for burial. But what about possible deaths in the five months for which records are missing? Surely men died during those months, and if so, then where are they buried? Some older residents in the vicinity of the cemetery allege that bones and/or skeletons were dug up at a site of a modern house within 25 feet of the south side of the present cemetery. If true, might these have been the remains of the possible "missing" soldiers?

Short of an archaeological excavation, we will probably never know the answers to these questions. My best guess is that the people who restored the cemetery during the 1908-1914 time period had access to the same hospital records that we are using today. The evidence strongly suggests that the headstones were intended to represent the graves of the 40 men who died in the Scottsville hospitals during 10 months of 1862-1863 (but not 1861-1865 as stated on the monument) and who are buried there. To view the soldier names on this monument, visit Monument.The isolated location, poor transportation, and inadequate facilities caused the Confederate Medical Department to abandon the Scottsville Hospital at the end of September 1863. However, the legacy of the hospital would forever remain in Moore's Hill Cemetery marked by the 40 unnamed headstones. For further details about the history of the hospital and cemetery, including the names of all the dead, please click on the following link to see Richard Nicholas' article entitled Confederate General Hospital and United Daughters of the Confederacy in Scottsville. (1999 issue, Volume 57, The Magazine of Albemarle County History published by the Albemarle County Historical Society.) |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

||||