"A good many tents are to be seen on Kiawah Island � The enemy are burning up the

woods to the North � There are 2 gunboats, 3 small steamers, 9 schooners � in the Stono River�

J.C. Hill, Capt." Thus read an 1864 intelligence report, submitted by Captain,

later Major, James Christian Hill. Before the War, Hill was a successful businessman of

Scottsville; during the War, a caring and effective leader of its men in uniform; and after the

War, an honored editor and citizen.

This future major was born May 29, 1831, in Charles City Co., VA. As a young man, Hill worked in a Richmond

mercantile business before moving to Scottsville in the late 1850's. There he operated a packet boat

business with John Owen Lewis of Cliffside, hauling freight on the James River and Kanawha Canal.

He quickly added a lumber business, and as his Scottsville business ventures prospered, so did

his personal life. He married Harriet Newell Ragland, and soon they had four children: Allan

C., Nancy Massie, John Parke, and James Christian Hill, Jr.

Eventually duty called. Shortly after Virginia seceded from the Union on April 15, 1861,

the Scottsville home guard mustered and departed for Manassas in early May. Great public

outpouring of grief accompanied the guard's departure. Still Brigadier-General Henry A. Wise

needed additional troops to save western Virginia for the Confederacy. Once again,

Scottsville rose to its duty and formed the "Scottsville Grays" with James C. Hill elected

as its captain. After three weeks of drilling and equipping, the Grays boarded a train to

Lewisburg, VA, where they joined up with Wise's 46th Virginia Regiment as its Company E.

Wise's campaign fared poorly in western Virginia, an area that had voted three-to-one

against secession. Local support to his troops fell far short of expectations, and recruitment

was disappointing. Ordered to Richmond, the 46th saw little action. In April 1862, Wise posted

the 46th to Chaffin's Bluff, overlooking the James River south of Richmond. The regiment's

mission was to guard the batteries there and stop any Yankee invasion of Richmond via the James

River. During their sixteen months at Chaffin's Bluff, the 46th drilled twice a day to

maintain military efficiency and discipline and responded to several false alarms along the

James. But it was starvation and disease, not bullets and shells that injured this regiment.

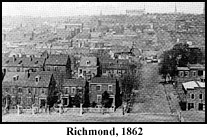

Soldiers and civilians jammed Richmond, and the city's population soared to 100,000,

outstripping its ability to provide food, shelter, and supplies. Inflation and small

pox raged unchecked. Documents in his Confederate Service Record show Hill's

constant efforts to obtain food and clothing for his men, who were not only his soldiers

but also his Scottsville neighbors. In a Jan. 9, 1863, letter to Col. Richard W.

Duke, commander of the 46th, Capt. Hill reported that his company was entirely without meat

rations. In his war memoirs, Hill described an incident that winter, involving

Sergeant Graham of Scottsville and several men from Co. E., posted at Gill's Shop in

Charles City Co. Supplied with rations for four days, Graham's detail, however,

was accidentally kept at this post for ten days. After exhausting his rations,

Graham purchased food for a day or two until his money ran out. He told Judas Gill,

the shop owner, that his men faced starvation and offered to buy Gill's hog on credit until

his commissary could pay for it. Gill refused, and faced with starvation, Graham

stole the hog. Furious, Gill reported the theft directly to General Wise, who ordered

a formal felony indictment prepared against Graham. At the Sergeant's court-martial,

Capt. Hill testified to his good character and that Graham shorted himself by sending all

of his money home to his poor, aged mother. General Wise was touched and turned to

Graham. "Sergeant, you did not steal Gill's hog. A soldier, who will husband

his pittance to give his mother, will not steal. The charge is dismissed�you are a

gentleman." Wise then turned his wrath on Gill, telling him that he would be shot

if ever found inside his lines.

Soldiers and civilians jammed Richmond, and the city's population soared to 100,000,

outstripping its ability to provide food, shelter, and supplies. Inflation and small

pox raged unchecked. Documents in his Confederate Service Record show Hill's

constant efforts to obtain food and clothing for his men, who were not only his soldiers

but also his Scottsville neighbors. In a Jan. 9, 1863, letter to Col. Richard W.

Duke, commander of the 46th, Capt. Hill reported that his company was entirely without meat

rations. In his war memoirs, Hill described an incident that winter, involving

Sergeant Graham of Scottsville and several men from Co. E., posted at Gill's Shop in

Charles City Co. Supplied with rations for four days, Graham's detail, however,

was accidentally kept at this post for ten days. After exhausting his rations,

Graham purchased food for a day or two until his money ran out. He told Judas Gill,

the shop owner, that his men faced starvation and offered to buy Gill's hog on credit until

his commissary could pay for it. Gill refused, and faced with starvation, Graham

stole the hog. Furious, Gill reported the theft directly to General Wise, who ordered

a formal felony indictment prepared against Graham. At the Sergeant's court-martial,

Capt. Hill testified to his good character and that Graham shorted himself by sending all

of his money home to his poor, aged mother. General Wise was touched and turned to

Graham. "Sergeant, you did not steal Gill's hog. A soldier, who will husband

his pittance to give his mother, will not steal. The charge is dismissed�you are a

gentleman." Wise then turned his wrath on Gill, telling him that he would be shot

if ever found inside his lines.

In early April 1863, Capt. Hill learned his wife, Harriet, was seriously ill and had been

transferred from Scottsville to a Richmond hospital. Hill requested urgent leave to be

at her side, but Colonel Duke declined, stating Hill was needed for the impending capture of

Williamsburg. Hill petitioned General Wise directly. Although sympathetic, Wise

explained that all of his officers were needed for the upcoming battle. Hill told the

General he was going to Richmond anyway, with or without permission. The General warned that

such action would mean desertion, capture, and court-martial. To this Hill responded,

"Hell yes, I know. But I'm going anyway!" Hill was on his horse ready to go when

the General's order came through, giving him permission to visit Richmond thirty-six hours

weekly during April. However, Harriet's condition worsened, and she died. On

April 25th, General Wise granted Hill ten-days leave to accompany her remains to Scottsville

and to make arrangements for his children's care.

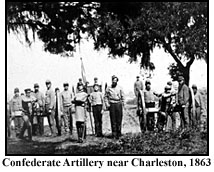

In September 1863, Richmond's safety seemed more assured with the renewed proximity of

Lee's army, and Wise's Brigade was ordered to report to General Beauregard in Charleston, SC.

Promised battle action after long months of post life, the 46th set off on a surprisingly

pleasant five-day journey from Chaffin's Bluff to Charleston on September 14th. They were

serenaded by bands and given fine dinners by ladies in towns through which they passed.

However, as they stepped off the train in Charleston, heavy guns boomed in the harbor.

Charleston was one of the Confederacy's most important ports and especially despised by

Northerners, whose constant presence posed a real threat to Charleston. Hill's men

spent long arduous weeks on guard duty, in constructing fortifications, reporting Union troop

movements, and defending the batteries along the Wappoo River.

In September 1863, Richmond's safety seemed more assured with the renewed proximity of

Lee's army, and Wise's Brigade was ordered to report to General Beauregard in Charleston, SC.

Promised battle action after long months of post life, the 46th set off on a surprisingly

pleasant five-day journey from Chaffin's Bluff to Charleston on September 14th. They were

serenaded by bands and given fine dinners by ladies in towns through which they passed.

However, as they stepped off the train in Charleston, heavy guns boomed in the harbor.

Charleston was one of the Confederacy's most important ports and especially despised by

Northerners, whose constant presence posed a real threat to Charleston. Hill's men

spent long arduous weeks on guard duty, in constructing fortifications, reporting Union troop

movements, and defending the batteries along the Wappoo River.

At Camp Duke on the Wappoo, Capt. Hill received word that his lumber business had been

totally destroyed by fire in mid-November 1863, creating a large financial loss.

On Nov. 23rd, he was granted twenty-days leave to attend to his confused affairs in

Scottsville. Always thinking of his family and soldiers, Hill stated in his leave

request that he also planned to make arrangements "for the care of my three infant children

plus to secure socks, shoes, and other clothing which my men very much need."

Upon his return to Charleston, Capt. Hill resumed command of Co. E and spent much of early

1864, guarding batteries on Johns Island and reporting the movement of Yankee troops, gunboats,

and other ships along the Stono, Folly, and North Edisto Rivers. Hill was promoted to

Major of Co. E on March 28, 1864.

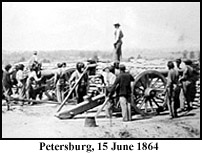

In early May 1864, Wise's Brigade received urgent new orders from Virginia-General Lee

needed every available man to defend Petersburg and Richmond. The 46th boarded a troop train

to Virginia on May 5th. At last they were returning home after endless months of guard duty,

camp life, and being held in reserve. But their homecoming would be violent.

Arriving at the North Carolina-Virginia border on May 7th, the 46th left their baggage

behind and began the arduous trip to Petersburg. The bridges and much of the track had been

destroyed, and they rode the rails when possible and marched when necessary. They finally

arrived in Petersburg on May 9th, exhausted. On May 15th, Wise's Brigade was ordered

to "march in the direction of the heaviest firing and attack the enemy in flank and rear" at

Port Walthall Junction.

All the months of drilling paid off. Wise's Brigade advanced with parade-day precision,

winning their first skirmish handily. The next eighteen days saw the 46th entrenched a

few miles east of Petersburg under heavy firing. Then a large Federal force moved

towards Petersburg with orders to seize the town and burn bridges north of it. All that

stood between the Federals and the key rear defenses of Richmond were the 500 men of the 46th,

a Georgia battalion, and various home guards. The Federals were repelled on June 9th,

and for the moment, the danger to Petersburg was over.

On June 12th, the greatest challenge to Petersburg began. Grant moved across the

James River with massive Federal columns and the fall of Petersburg as his strategic objective.

Until Lee's Army of Northern Virginia arrived, Beauregard could only shift his men along the

lines to meet the threats as they arrived. The fighting was fierce as 10,000

Confederates tried to hold off nearly 90,000 Federal soldiers. The 46th lost two

commanders in two days of heavy fighting, and Major Hill took over command on June 16, 1864.

Hill's regiment moved to a new position on June 17th next to the 23rd South Carolina

behind Harrison's Creek. No breastworks existed there, and Hill's men dug in

frantically while under fire from Federal batteries and sharpshooters. When the South

Carolinians panicked and abandoned their post, Hill ordered his regiment to fall back to

woods' edge where he rallied them and counter-charged the works they had just abandoned.

Taken by surprise, a Yankee officer called out, "What regiment is this?" Jumping up on

a traverse, Major Hill shouted, "The 46th Virginia!" The Yankee yelled back, "Give it

to them boys!" and a volley struck down Major Hill and several others. The regiment

again fell back to the woods, and the day's fight was finally over.

The first bullets reportedly struck the cap from Major Hill's head and knocked the sword

from his hand. Other bullets hit his arm, severely damaging it and effectively ending

his military career. Two Scottsville privates carried Hill from the battlefield to

shelter; Hill was later admitted to Petersburg General Hospital before officially being

transferred to private quarters in Scottsville. Hill would convalesce until early 1865

at Chester, the home of his mother-in-law, Mrs. Ragland.

The first bullets reportedly struck the cap from Major Hill's head and knocked the sword

from his hand. Other bullets hit his arm, severely damaging it and effectively ending

his military career. Two Scottsville privates carried Hill from the battlefield to

shelter; Hill was later admitted to Petersburg General Hospital before officially being

transferred to private quarters in Scottsville. Hill would convalesce until early 1865

at Chester, the home of his mother-in-law, Mrs. Ragland.

On March 6, 1865, General Sheridan rode into Scottsville at the head of a troop of

Federal soldiers intent on destroying the James River and Kanawha Canal locks. As his

troops looted the town, Sheridan chose Cliffside as his temporary headquarters. Just

down the street, the invalid James Hill feared for the safety of his children, Mrs. Ragland,

and their servants. Knowing he most likely would be arrested and carried away, Hill

wrote General Sheridan, explaining the family's situation, and asked for a guard to protect

the house. He sent the note to Sheridan via his son, Allan, who was stopped at

Cliffside's gate by a sentry. Breaking away from the sentry, Allan ran for the door,

ducked between another sentry's legs, and dashed into the house to deliver the note directly

to Sheridan. Sheridan read the note, patted Allan on the head, told him he was a brave

little boy, and gave him an apple. He also gave Allan a note, saying a guard would be

posted at the Hill house. The next day, two Federal soldiers came to find out the

extent of Hill's wounds. One said to the other, "No use taking him, we don't want dead

Rebs."

After the Federals left Scottsville, James Hill moved his family in with the Lewis family

at Cliffside. When the war ended, Hill married Mary Emory Lamb on May 3, 1866, in Charles

City Co., VA, the sister of his longtime friend, Capt. John Lamb. This second marriage

added five more children to the Hill family: William, Susan, Anne Elizabeth, Emory, and

Frank. Initially, Hill supported his family with income from his partnership in Hill,

Lewis, and Co. and also operated the Scottsville Courier as its editor. Much esteemed

as Scottsville's highest-ranking officer, he was frequently asked to speak about the war and

his experiences. Hill's arm never healed and in 1874 required amputation, garnering

him almost heroic status among townspeople for his War sacrifices.

By 1878, Hill's boat business failed, as it could no longer compete with the railroad for

freight and passengers. He eked a modest living from the publication of his newspaper,

using persuasion and humor to inspire the town as it struggled to rebuild. In 1885,

Major Hill served as sergeant-at-arms of the Virginia House of Delegates and worked tirelessly

to rebuild Virginia's transportation system as a Railroad Commissioner from 1887-1900.

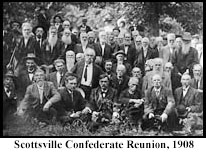

Shortly before his death in 1906, Scottsville honored Hill with a grand celebration.

A torchlight parade, which included nine prominent members of the Virginia Legislature, streamed

up Harrison Street to Hill's house near the Baptist Church. As Hill stood on his front

porch, the parade folks sang "Let all the Hills rejoice," a song specially composed for the

occasion. When Hill died, the two Scottsville privates, who carried him to shelter at

Petersburg 40 years before, were guards of honor. They fired a volley over his grave at

Scottsville Baptist Cemetery as taps were sounded by one of his old soldiers.

Shortly before his death in 1906, Scottsville honored Hill with a grand celebration.

A torchlight parade, which included nine prominent members of the Virginia Legislature, streamed

up Harrison Street to Hill's house near the Baptist Church. As Hill stood on his front

porch, the parade folks sang "Let all the Hills rejoice," a song specially composed for the

occasion. When Hill died, the two Scottsville privates, who carried him to shelter at

Petersburg 40 years before, were guards of honor. They fired a volley over his grave at

Scottsville Baptist Cemetery as taps were sounded by one of his old soldiers.

General Hill is Dead - Distinguished Confederate Veteran Answers Last Call

Daily Press, Vol 11, Number 225, p. 4

22 September 1906

Scottsville, Sept. 21 - General James C. Hill died at his home here at three o'clock this morning. The burial will take place at 4:30 Saturday

afternoon.

General James Christian Hill was born nearly seventy-six years ago in the county of Charles City. He made that county his home for several

years, engaging in various pursuits - farming, merchandising, and such general business as presented itself. He was educated in Virginia schools

and by private tutors.

When war was declared, he enlisted as a private and served till he was wounded in defence of the city of Petersburg in 1864, when he lost an arm.

After the war, General Hill removed to Albemarle County, his home being at Scottsville He was elected a member of the general assembly

and was also at one time the sergeant-at-arms of that body. About twenty-four years ago, he was named for the position of railroad

commissioner, a position which he held till the constitutional convention provided for a commission consisting of three men. In that position,

he gave satisfaction to the State and to the railroads.

General Hill was twice married. His last wife, sister of Congressman John Lamb, survived him, with several children, all of whom are

grown as follows: Allen C. Hill, of Baltimore; Frank T. Hill of Mexico; Miss Nannie and Bessie Hill, of Scottsville; Mrs. M.I. Dunn,

of Kentucky, and Emory Hill, of Albemarle, and one sister, Mrs. Josephine Trevillian.