|

|

| ||||||

by Captain Bruce R. Boynton, USN | ||||||

"They had for us all the glamour of Robin Hood and his merry men, all the courage and bravery of the ancient crusaders, the unexpectedness of benevolent pirates and the stealth of Indians." Thus wrote Sam Moore, a young man from Berryville, of the fascination held by the people of western Virginia for Confederate Colonel John S. Mosby's Partisan Rangers (43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry). With such a reputation, it is no wonder that Mosby found it easy to attract recruits. The life of a Ranger, the changing scenes, the danger, and wild adventure lured many men to the battalion. Officers in other units gave up their commissions to enlist as privates. Old soldiers and those who had been discharged as unfit for further service also joined. Some recruits to the unit were too young to enlist in the regular Army, while others had been foreign soldiers of fortune. Among the Battalion's youngest members was a 16-year-old Scottsville boy named Henry G. Harris.  Henry's parents, Miletus and Frances Harris, had moved to Scottsville from Louisa County about 1837.

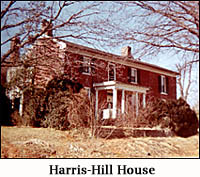

Frances was a milliner and opened a shop in town while Miletus ran a general store. The young

family moved into a two-story brick house on Harrison Street, next to the Baptist Church. The

house, since torn down, stood where the church parking lot is now. The front of the house had a

medium sized porch supported by four large columns. A door on the upper floor opened directly

onto the porch roof. Henry was born on July 2, 1847, the fourth of five children. His older brother, John, was a Major in the Confederate Army, and his sister, Mollie, had married a Lieutenant in the Scottsville Grays (Co. E, 46th VA Infantry). Naturally, Henry was anxious to do his part for the cause, but his mother was adamantly opposed. Being underage, he could not enlist without her permission. However, Henry was undeterred. One night in the spring of 1864, while the rest of his family was asleep, he climbed out upon the porch roof, slid down one of the columns, and escaped. He made his way north, probably to Fauquier County, where he enlisted as a Private in the 43rd Battalion, Virginia Cavalry.

By the spring of 1864, the Battalion had grown to such an extent that a fourth Company, Company D, was organized at Paris, Virginia, on March 28. It was into this Company that Henry Harris enlisted. Company D became known as Company "Darling." This unwarlike nickname had its origin in the extreme youthfulness of its members and the observation that the Rangers made just as deep an impression on female admirers as they did on the enemy. Henry was neither the only teenager in Company D or the only Ranger from Scottsville. A survey of the Company's roster shows that there were many other teens in Company D, though none younger than Henry. Teens were welcome in the Rangers; indeed, Mosby preferred them. "They are the best soldiers I have. They haven't sense enough to know danger when they see it, and will fight anything I tell them to." Four other Scottsville boys served in Company D: Zach F. Jones, John T. Beal, and two Moon brothers, Jacob and James H., known as the "Daredevil Moons." Life in the Rangers was very different from that in other Confederate cavalry units. There were no camps, uniforms or drill. Mosby's men did not remain together between engagements. Mosby commented that if his men had set up a camp they would have all been captured. After a raid, the Rangers dispersed to individual homes where they boarded or else bivouacked in the woods. Over 80 per cent of the Rangers were from Virginia and consequently, the Battalion enjoyed overwhelming popular support. As a Federal cavalryman noted, "Every farmhouse in this section was a refuge for guerrillas, and every farmer was an ally of Mosby, and every farmer's son was with him, or in the Confederate Army." In return, the men shared the loot they captured with their civilian supporters. After a wagon train raid at Berryville in August 1864, the Battalion gave half of the captured cattle to the families that fed and boarded them.

Uniform, to Mosby's men, meant something gray. Otherwise the men might dress as they pleased. Many Rangers used their share of any captured money to outfit themselves with gold braid, gilt buttons and ostrich plumes in their hats. As one Ranger commented, "There were meek and lowly privates among us, of whom it might truly be said that Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed as one of these." This sartorial splendor was most prevalent in Company "Darling." One Ranger commented that the company seemed to contain nothing but dandies who, in order to maintain their prestige, were obliged to fight all the harder. Capt Montjoy, the company's commanding officer and a sharp dresser himself, was exceedingly proud of his company of fighting dandies. The Battalion did not carry sabers or carbines, the traditional cavalry weapons. Mosby found that carbines, while useful for sniping, were ineffective in the close-quarters fighting he preferred. His men found sabers more useful for whacking recalcitrant mules than for fighting. The weapon of choice was the forty-four caliber Colt revolver, with which the men practiced constantly to perfect their marksmanship. The Rangers were as unconventional in their tactics as they were in their dress and weaponry. One Ranger noted that the Battalion had no knowledge of drill or bugle calls and practiced nothing required of a soldier. A Confederate Army inspector complained that the Battalion didn't seem to keep any paperwork. There were no rolls, files or descriptive books required by regulations. Although the Rangers appeared disorganized by ordinary standards, their success was the result of careful scouting, meticulous planning, and daring raids. Mosby used fear as a force multiplier. The Federals never knew where he might strike next and so tied-up large numbers of troops protecting their flanks and rear. Throughout the spring and summer of 1864, the Rangers attacked Union camps and wagon trains. On July 4, Mosby attacked a Union supply depot at Point of Rocks, Maryland, in the famous "Crinoline Raid." The Rangers came under fire as they crossed the Potomac River into Maryland but soon drove the Federals away. Union troops retreated across the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and removed the flooring from the only bridge across the waterway. The Battalion promptly tore down an adjacent wooden office building and proceeded to repair the bridge under fire. The enemy continued to fall back, and Mosby cut the telegraph lines and burned the camp. Four village stores were relieved of their surplus calico, boots, shoes, and tin ware. One of the participants later wrote that the large number of hoops, ladies skirts, and bonnets carried away by the raiders showed that they had not forgotten the "girls they left behind them."

Although Mosby's tactic of dispersing his men after a raid preserved the Battalion from destruction, it increased the risk of capture for individual Rangers. A review of compiled muster rolls shows that 360 Rangers were captured during the war. However, capture could have fatal consequences. On August 16, General Grant had ordered General Sheridan to hang any Ranger he caught without trial. On September 23, six Rangers from Company D were captured during an attack on Union cavalry reserves near Chester Gap. The men were taken to Front Royal and summarily executed. As might be expected, this action enraged the Rangers and led to the execution of a like number of Union prisoners.

Because the prison was not separated from the rest of the city, it was possible for a prisoner to signal passers-by on the street outside. Prison guards took special pains to prevent this and threatened to shoot prisoners who approached the windows and arrest citizens who acknowledged them by waving. There were several escape attempts. Ranger John Munson, who was a prisoner in Old Capitol during the time Henry was there, successfully escaped by disguising himself as a hospital orderly and walking out the door in full view of the guards. Although the living conditions in Old Capitol Prison do not appear to have been particularly severe, the prisoners did complain about the food, especially when they found they were eating beef and pork from barrels that were stamped "I.C.", meaning "inspected and condemned." On February 6,1865, Henry and 85 other Rangers were transferred from Old Capitol to Fort Warren in Boston harbor. The men were handcuffed in pairs and marched to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad depot under the watchful eyes of a Lieutenant and 28 armed guards. Ranger Hugh McIlhany, a fellow prisoner, described the scene. "A more enraged set of men were never seen than these, when standing on Capitol street, handcuffed together. When Clark, the superintendent of the Old Capitol Prison was asked for a reason for such treatment, he said it was a shame, but believed the officer was afraid and unwilling to start on the journey unless they were handcuffed.

3d Reunion of 43rd Battalion, VA Cavalry, Mosby's Men

Photo on Capitol Steps, Richmond, VA, July 1, 1896 Henry Harris' head and shoulders are outlined in the white box in the photo above. In total, 99 of Mosby's Men are shown in this photo and identified on the original photo by number. The complete list is included below:

|

|

|

Bibliography: Photo Credits: Henry G. Harris; Williamson, James J. Mosby's Rangers. New York: Ralph B. Kenyon, 1896. Reprint, Time-Life Books Inc., 1982; p. 461.(JJW02cdJJW01) |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

||||