|

|

|

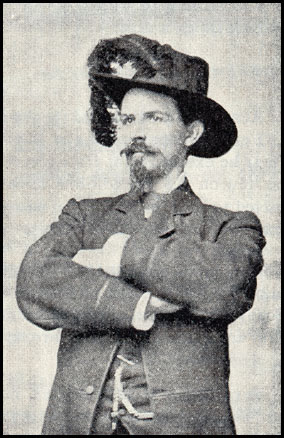

Name: Zachariah Fleming Jones, Mosby's Ranger Date: ca. 1864 Image Number: JJW01cdJJW01 Comments: Zachariah Fleming Jones enlisted in Company D, 43rd Battalion Virginia Cavalry, Mosby's Command in 1864 at the age of seventeen. He was a dashing figure in his Confederate uniform, and in later years, Zack often spoke of the daring exploits and narrow escapes of Mosby and his men. Mosby's Rangers included some of the best horsemen in the country, who frequently traveled by night on raids about the countryside. Again and again, Zack's horses were wounded under him. During a March 1865 battle at Tyson's Corner, Virginia, Jones narrowly escaped death when his horse reared up and took the bullet intended for his rider. Zachary Jones was paroled at Columbia, Virginia, at war's end and spent the rest of his life in Scottsville. In her 1908 application to the United Daughters of the Confederacy, Mary Virginia Jones, Zack's oldest daughter, described several of her father's exploits with Mosby's Rangers:

"In a fight near Ball's Bluff (near Leesburg, Virginia), where our men attacked 22 of the enemy, Mr. Zack Jones narrowly escaped death. A Yankee attacked him and as he fired, the horse reared up receiving in its shoulders the shots intended for Mr. Jones." James J. Williamson, Company A, Mosby's Command, described the above March 12, 1865, skirmish in his book entitled, Mosby's Rangers: A Record of the Operations of the Forty-Third Battalion Virginia Cavalry (1896): "Sunday, March 12: A detachment of between 40 and 50 men, under Captain Glascock, from the command quartered in Loudoun, was sent to Fairfax to attack a cavalry patrol." "Arriving at a point on the road near Lewinsville, where it was expected the patrol would pass (a little hollow in the pines), Captain Glascock, Bush. Underwood and Thomas Moss went to the edge of the pines to watch the road. The patrol, numbering 22 men from the Thirteenth New York Cavalry, soon came along. Moss was sent back with orders to bring forward 10 men, who were put in charge of Bush. Underwood with instructions that, as soon as the enemy passed to cross over in their rear, in order to pick up any who might escape Captain Glascock, who would attack in front." "The Federals, seeing us, halted, but mistaking us for some of their own men, again moved on. Glascock, thinking they were about to retreat, ordered a charge, and the fight which ensued being in a narrow road, at close quarters, was very destructive to the enemy, 12 of whom, dead or wounded, lay on the ground at the close, together with 6 horses killed. Nine prisoners were taken. Our loss was one man, Francis Marion Yates, of Rappahannock, who was accidentally killed by our own men in the charge." "Ed. O'Brien was wounded in the leg, and Thomas Moss was injured by his horse falling with him. Zach. F. Jones had his horse badly wounded." Zack Jones had his horse shot out from under him on numerous occasions. Once his horse was so badly wounded that Zack could not make it go. His comrade and fellow Scottsville citizen, Luther Moon, stayed back with Zack and forced the horse along. Zack recalled years later that had it not been for Luther's actions, he probably would have been captured or killed by the Yankees in that skirmish.

"Soldiers: I have summoned you together for the last time. The visions we have cherished of a free and independent country have vanished, and that country is now the spoil of a conqueror. I disband your organization in preference to surrendering it to our enemies. I am now no longer your commander. After an association of more than two eventful years, I part from you with a just pride in the fame of your achievements, and a grateful recollection of your generous kindness to myself. And now, at this moment of bidding you a final adieu, accept the assurance of my unchanging confidence and regard. Farewell! John Singleton Mosby" When Mosby's farewell was read, a profound silence ensued. His men gave Mosby three hearty cheers, and the order was given to disband. Hardly a dry eye could be seen. Mosby stood beside a fence and shook hands with all of the men who gathered around him. Later in the day, Mosby's men rode off to various Virginia locations to accept their paroles, and Zack Jones was paroled at Columbia, Virginia. Zack Jones and his fellow Rangers remained committed to their old comrades and to Col. Mosby for life.  Zack returned home to Scottsville to help his father, Benjamin Haden Jones, on the family farm two miles

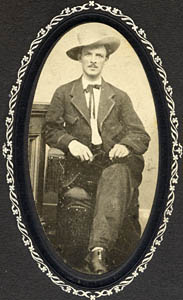

north of town. He remained a dashing figure throughout his life, as can be seen in this 1867 photo of Zack

with his neat moustache and hat cocked at a jaunty angle. By 1880, Zack worked as a drummer, who traveled

about the countryside to sell various farm products. Perhaps it was during his drummer years that Zack's entrepreneurial

spirit was awakened; by 1895, Zack had a fistfull of U.S. Patents for his inventions that included a nut-lock, a plow protector,

and new wagon bodies. He also met Cornelia Ann Crew, his future wife; they were married on March 2, 1881 By 1893,

Zack and Cornelia Jones were the parents of four children: Mary Virginia, Benjamin Crew,

Robert Dameron, and Annie Warren Jones. In 1897, Zack Jones purchased a three-acre lot with a

frame house called 'Breezewood' on the western outskirts of Scottsville and moved his family to town. In 2005,

Breezewood sits on the west side of Scottsville Library in town. In his spare time, Zack kept in touch with his Confederate colleagues by frequent visits to Billy Beal's Palace on Valley Street where old soldiers sat around on the front porch and talked of their war experiences. He was also attended Confederate reunions and is shown in the photograph below of the Third Reunion of Mosby's Command on the Capitol Steps in Richmond, VA, on July 1, 1896; Zack's head and shoulders are outlined in the white box in the photo below.  When rumors of an impending Spanish-American war reached Scottsville in 1898, Zack Jones and Luther Moon wrote a letter to John S. Mosby, who then lived in San Francisco. Although 52 years of age at the time, the two men informed Mosby that they would gladly serve under his command as the U.S. government went to war. On March 25, 1898, John Singleton Mosby provided the following response: San Francisco, Cal. Mr. Zach. F. Jones -- Dear Jones: Your Sincere Friend,

Last week you published a war-time illustration and under it was the legend, "Charge of the Nineteenth Infantry." Doubtless there were other regiments present at Gettysburg in 1863, but there was only one Nineteenth in the eyes of a Virginian --- that commanded by Colonel Henry Gantt, and of which the "Scottsville Guard" was a part, known as Company C. So I looked at that picture and tried to imagine just what part of the line was held by the boys from the old home town. Last Saturday, the adjutant of Henry Gantt Camp, No. 47, U.C.V., wrote me as follows: "If you want to see what's left of the old boys, some of them from your father's Company, meet us at Union Station." Was I on the job? You can bet your sweet life I was, and I wouldn't have missed it for a year's salary --- God bless their dear old souls? This, then, and seeing that picture last week, is responsible for my taking up a little of your space to tell about what I saw of the reunion. Imagine, if you can, every man, woman, and child in Scottsville assembled on the old Fair grounds with a few from Fluvanna and Buckingham thrown in for good measure; and then imagine every one in the crowd to be as old as Bill Londeree (and he is the youngest old man I ever saw); then count'em up and multiply of what this reunion of old fellows looked like. Fifty-five thousand men whose average age is 72 years! Think of it! After all, I'm not going to talk of Gettysburg, but about "the boys." Well, here are the ones I saw: George W. Patteson, commander of your camp; George Wash, and Buckingham can't boast of a finer fellow; and the adjutant, Uncle Henry Harris, if I may put it in that personal way; W.P. Londeree and John W. Moon, of the 19th; Vincent A. Cobbs, of the 46th; Captain H. C. Bragg, of the 47th; J. Eli Hughes of the 44th; J.R. Maupin of the 56th; Zack Jones, of Mosby's Command; J.M. Ramsey, in the artillery branch of the service; James S. Harris, of the quartermaster's department; and then Charles Steger, Edmund Banton, the Buckingham troops. George and John Nicholas, the former in Pickett's Brigade; James P. Moon, a sharpshooter of the 46th; and Tom Childress of the 15th Cavalry, got through town without my seeing them, as also did Pres Collins of the 10th Cavalry, and Walker Gilmer, of the 19th Regiment. You folks back home who see these men from day to day, individuals, members of your own community, probably do not appreciate what the sight of them as a company, dressed in the old gray uniform, meant to me. Most of them, as a youngster, I knew. If the tear-ducts had not been in good working order, I think the lump in my throat would have choked me to death. There were some faces I expected to see that did not show up: Jonathan Pitts, of the 19th; Miles Heath, of the 44th; Charlie Staton, of the hospital staff; and Nick Graham, Tom Harris, Sam Thompson, and John T. Noel, all of the 46th, my father's regiment. I have often wondered why it was that father, who started in the war as first sergeant, should have served four full years and never received a promotion. I found out this week, and here's the answer in the old soldier's own words: "Allen Hill was such a d----d good orderly sergeant, the best in the army, that we wouldn't let him be promoted, we would not vote for his advancement. When Watts was made captain, it was his job, but we wanted him for our orderly." So you see, I might have been the son of a general, or a captain anyhow, if it hadn't been for Vinc Cobbs, Nick Graham, Sam Thompson, and a bunch of those other dare devils in Company E, 46th Virginia. But the thing worked both ways. On a certain occasion, one of the old boys told me, Major Hill, who was a strict disciplinarian, reduced his first sergeant to the company to elect a new one. They told the Major, diplomatically of course, that they wouldn't vote for any one else--and they didn't." Dear old boys, I couldn't help thinking of those others who have preceded these survivors and now rest, please God, with Stonewall "under the trees." Among them were: John Page and Phil Darneille, lieutenants in the "Scottsville Grays," which went out under command of Captain Jim Hill, and became Company E of the 46th, Captain Hill afterwards becoming its major; Ned Blair, Elias Mahoney, Charles Irving, John Blair, George Napier, Virginius Jefferies, D. Scruggs, Tom Griffin, Jerry Cleveland, and William M. Wade. Mr. Wade, father of Dr. Willie and Dick, was a volunteer aide on General Magruder's staff, and the first Scottsville boy, so I am told, to lay his life a sacrifice on his country's altar. Scottsville furnished thirteen young men to the 43d Battalion Virginia Cavalry, known as "Mosby's Men." They were: John Llewellyn, Felix Ware, John Beal, Phil Darneille, Jim Moon, Luther Moon, Buck Staton, Billy Gibbs, Lorenzo Sanders, John A. Alexander, Joe Beal, Zack Jones, and Henry Harris. The last three are all that are left of that brave little company, and of these Comrades, Jones and Harris bivouacked on the Gettysburg field last week. Captain Bragg, of Howardsville, was one of the oldest in our party, but was as lively as a cricket. He was reminiscent of the old freight-boat days, and we talked of Billy Burgess, Buck Staton, and some of the younger ones who helped to make up the life in canal times. The Captain got lost in Gettysburg, and the other boys didn't find him for two days. The Scottsville contingent got into camp late Monday night, and arrangements had not been made to take care of them. By some means, more by accident than design, the Captain was given sleeping quarters in the hospital, and he liked it so well, he stayed there. But the others were scared up over his absence till they saw him on the third day, riding around in some Yankee's automobile. Speaking of Yankee, every Yank in camp tried to shake hands with every Johnny Reb, and the Johnnies, apparently, tried to go them one better, with the result that our fellows toward the wind-up felt like they had rheumatism, neuritis, pen paralysis, and every other similar kind of ailment. This may explain why it was that when a big individual with brass buttons down the front, and G.A.R. on his cap, extended his hand in fraternal greeting to Henry Harris, Adjutant Harris failed to see it -- in fact, he hasn't seen it yet. Of the Scottsville boys at the reunion, four at least were in Pickett's charge: Captain Bragg, Walker Gilmer, J.R. Maupin, and Charles Steger, and all, I think, were in different regiments, though I am not certain about Steger. The gallant Henry Gantt led the 19th and was shot in the face. He carried the scar as a disfigurement down to the grave. Walker Gilmer, of the same regiment, also stopped a minie ball on the heights of Gettysburg, it lodging just back of the eye, where he carried it for over thirty years. George Nicholas, on the first day at camp, started out from Spangler's woods, where Pickett's Brigade formed for the charge, studying the markers, which have been placed by the government to show the position of the two armies. Several of the boys were with him, and as he got the lay of the land, he began to let fall such remarks as, "We formed just about here." "At this point the order was given us to double-quick." "Here's about where we paused to close our ranks before making the final dash," etc. Finally one of his comrades who knew the facts, said: "George, you know d--n well you were in the hospital during the Gettysburg campaign. Why in h--l don't you change the pronoun?" Nothing could be more natural than a member of Pickett's Division, that storming force which had been called "a veritable Tenth Legion," should refer to the charge as "ours," and the good-natured banter was just in fun. The man who made it knew George Nicholas, if he had been able, would have been right there facing the deadly greeting of grape, canister, and minies, and his wounds would have been in front, as were Gantt's and Gilmer's. Another Scottsville boy who missed the charge was Bill Londeree, also of the 19th, and he told me that the only thing that kept him out of Heaven on July 3d, 1863, was a mess of onions. A few days before that, on the march, Bill passed an onion patch. Filling his haversack, he lugged them along until a halt was made for the night. Then he cooked them and ate a square meal---nothing but onions. Next morning, he had to be sent back to the hospital, and the battle of Gettysburg had gone into history before he answered another roll-call. W.P. says he knows he would have "got his" if he had been in the fight, because out of the eighty men in his company who went in, only ten came back. The odds certainly would have been against him. But think of that casualty list! Eighty-seven and a half per cent! No wonder it took four years and all the world's resources to lick Lee's army---composed of men who could retire in good order under such terrific punishment. And did they really lick us? I heard an old fellow from Georgia say this to a Yankee vet the other day: "Whip us! Well, Yank, you didn't! We wore ourselves out licking you." Both of them laughed over the pleasantry, but isn't there a world of truth in it? I prefer to think that of men who could make a charge like Pickett's, of which it has been said by an English historian: "The charge of the Light Brigade was less desperate and its trial far less prolonged. The bravest among the victors of Inkerman or Albuera, of Worth and Gravelotte, might envy the glory of Pickett's defeat." War is a terrible thing, and was especially hard on the South where the cradle and the grave were robbed, as the years went by, to fill the ranks. And some never came back, or coming were maimed for life. Take one Buckingham family for example: John, Lee, David, Rice, and Augustus Patteson all went into the war full of hope, inspired by the righteousness of their cause. Three never came back, and the other two were badly wounded. Well, thank God, there can never be another like it, in this country at least. The reunion at Gettysburg removed the last doubt, if indeed any remained, of the loyalty of all our people to the Stars and Stripes. The Bonny Blue Flag and the Stars and Bars are now just a precious memory, but they will always stand for unfaltering devotion to a principle--an inspiration to our Southern youth so long as love of country is esteemed a virtue. At Gettysburg, where a party of Northern veterans was paying a friendly visit to the Confederate camp, one of them said to a Louisiana Tiger, "Johnny, can't you fellows give us the rebel yell once more just for luck?" "No, sir-ree, Yank," responded the Louisianian, "I don't want to break up this picnic--am having too good a time. If we gave the rebel yell, you fellows would run like h--l just through force of habit." To which the Yank replied: "Johnny, the drink's on me, let's go to it!" Twenty-five years ago, that kind of talk would have brought on a bum argument. Today--well, they are all brothers, those old fellows of the Blue and the Gray, and take pride in admitting the courage and valor of their opponents. Yes, fifty years has been sufficiently long to wipe out the sting of defeat; yea, and to take away the vain glory and boastings of victory. Gettysburg in 1913 presented the calm of a Methodist love-feast, and it was a beautiful thing, and not without its pathetic touch to see a soldier who fought on Round Top with his arms around a gray-clad veteran, who charged up the heights with Pickett, and both of them crying like children. And there were hundreds of cases like this. Here's one: A Confederate, wandering through Devil's Den, remarked to a comrade that it was just about here that he was badly wounded and captured. Just at this moment, a party of G.A.R. men passed them, and one was saying, "Right along here, about the close of the battle, a Confederate fell, wounded, right in my arms, and I carried him back to the rear." The Confederate soldier heard him, and walked over to the group. "I was that rebel, Yank," he said, "and I remember you." The recognition was mutual, and they were in each other's arms instantly, the tears streaming down their cheeks. This was not an unusual instance at the reunion; there were others, but it will take too much time to tell of them. And when the Southern boys passed through the town on their way to the station, almost every

one with his arms linked through that of a Union veteran, it was like the passing of a

victorious army with banners. Every porch, every window was filled with women, from

all parts of the country, waving flags and handkerchiefs, throwing kisses to the gallant old

Confederates, and bidding them God-speed on the homeward journey. As the train pulled out,

the last words one heard were: "Good-bye, Yank!" "God bless you, Johnny!"

Allen Hill's Son

NOTE: Where I have used Christian names in this article, it has been with the idea of giving personal color for the "old boys" themselves. Those of us born during reconstruction times have too much love for the men and the cause to speak disrespectfully or irreverently of either. The top photo of Zack Jones and the photo of the Mosby Scout on horseback comes from Mosby's Rangers by James J. Williamson (New York: Ralph B. Kenyon, 1896; p. 87). The 1867 photo of Zack Jones is part of the Robert Ash collection. Robert is the great grandson of Zachariah Fleming Jones; he resides in Rock, West Virginia. The 1898 letter from Col. John S. Mosby to Zach. F. Jones and the 1913 photo of Zach Jones at Gettysburg are part of the Raymon Thacker collection. Raymon resides in Scottsville, Virginia. The July 1913 article above, written by John C. Hill, is part of the Meta Hill Erb collection. She believes the article was written by her uncle for The Roanoke Times where he had been a cub reporter as a young man. Mrs. Erb is the niece of John C. Hill and granddaughter of Richard Allan Hill; she resides in Roanoke, Virginia. References:

1) 43rd Battalion Cavalry - Mosby's Command by Hugh C. Keen and Horace Mewbom (Lynchburg,

VA: H.E. Howard, Inc., 1993). Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

||||