|

|

|

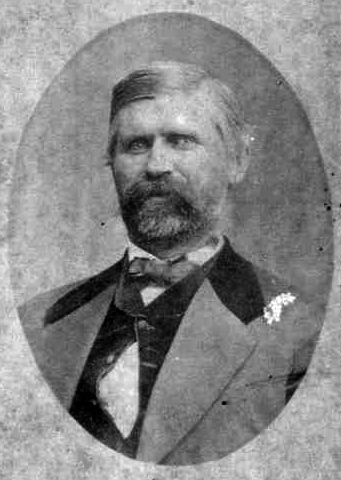

Name: Captain John B. Anderson, Company C, 60th Virginia Infantry Date: ca. 1862 Image Number: JPW001 Comments: John B. Anderson was born on December 1, 1819, in Louisa County, Virginia, and was the son of John Anderson (1782-1862) and Nancy (Lasley) Anderson (1787-1854). On May 16, 1843, John married his first wife, Mary Elizabeth Morris (1823-1893), of Scottsville, Virginia.  Mary Elizabeth (Morris) Anderson, ca. 1875 John B. and Mary Elizabeth Anderson were the parents of ten children:  John B. Anderson's Civil War sword, which hung over the mantle at the home of his son, D. Wiley Anderson at Albevanna Springs near Scottsville. John's sword is now on display at Scottsville Museum, thanks to its 2019 donation by Jean Williamson. Thank you, Jean!  Above is a closeup of the clip on John B. Anderson's sword which hooked over his belt. After the Civil War, John B. Anderson returned to his family and his 1000-acre farm near Scottsville. Like most Southerners after the War, the Anderson family had to start over as the plantation system was extinct. After the war, the Anderson family tradition reports that a number of former slaves and their descendants continued to live and work on or near John B. Anderson's farm well into the twentieth century. As Virginians had little money after the War, farmers like John shared, traded, or made what they needed to run their households. According to the recollections of John's granddaughter, Nettie Troth, John taught his 9 children and the hired help the skills of barrel-, broom-, and furniture-making, and the Anderson children probably worked in the field alongside the hired help at times. The Anderson family developed an enduring work ethic and learned how to survive in hard times. John B. Anderson and his wife, acquired lands near Scottsville amounting to about a 2,000 acre plantation at its height, spreading from Blenheim Road east north of Scottsville. John B. Anderson became an accomplished carpenter and parlayed this talent into a reputable building business. Four houses built in Fluvanna County circa 1880 (Rivanna Farm, The Homestead, Oak Grove, and Old Gold Mine Farm) are attributed to him. John also used his buiding skills to erect several churches (including St. John's Episcopal Church in Scottsville) and an old covered bridge over the Hardware River at "Temperance Wayside." John's son, D. Wiley Anderson, worked with his father on building projects from his teens until at least his mid-twenties and garnered a valuable background in the craft of building. This practical building experience later enhanced D. Wiley's practice as a Virginia architect. John's wife, Mary Elizabeth (Morris) Anderson, passed away on July 31, 1893, at the Anderson farm. John's second wife was Nancy Kidd (1841-1934), whom he married on July 24, 1894. John B. Anderson passed away on October 17, 1911, near Scottsville, and he is buried at the Anderson cemetery at Albevanna east of the Anderson home. Keith Anderson Van Allen, great grandson of John B. Anderson, believes this monument was erected by D. Wiley Anderson and that John B. Anderson is buried with other family members in this small fenced-in enclosure which is likely overgrown at this point (2022). Keith said that he last saw this cemetery as a boy. Directly behind these graves was the Slave Cemetery of the Anderson slaves, unmarked, but they were for many years discernable. To learn more about John B. Anderson, read this excerpt on him from "Memories of Bygone Days" by Thomas Cleveland Sadler (self-published in 1971). Sadler married 1) Mary Willie Anderson (1891-1918), and 2) Fannie Lee Anderson (1894-1980). Both of his wives were daughters of Philip Leland Anderson (1855-1922) and granddaughters of John B Anderson. In his opening comments in the book, Sadler dedicated it to his dear wife, Fannie, on their 50th wedding anniversary.

Captain John B. Anderson Captain John B. Anderson was the grandfather of both of my wives. He died when I was a young man so almost all that I can write about him is what they, their father, my father, and others told me. But I did know Captain Anderson long enough and well enough to wish that I had known him better. He was very rough spoken and might scare you to death if you did not know him, but he was one of the most tender-hearted men that I have ever known. He was a devoted member of Wesley's Chapel Methodist Church for many years. He would drive his horse and buggy about six miles every Sunday to be there. He loved music, and they had no organ at church, and so he bought a little one that you put sheet music in, I think, and turned by hand. I attended Antioch Church which was on the road Captain Anderson had to go to his church. I would see him go by with the organ tied on the back of his buggy. He would grind out some music at church, and then he and his wife both would help with the singing. Now some of the many stories told about Captain John B. Anderson: FIRST HIS COURTSHIP Captain John Anderson's first wife died when he was about seventy-five years old. About a year later, I suppose he realized that he needed someone to help take care of him in his old age, and so he decided to go courting. There were two old maids whom he had known for a long time, who were members of the same church to which he belonged. So he decided to see them first, although I have heard that he had a third one in mind if he should not have any luck with the first two. So one morning he hitched his horse to the buggy and started out. His first stop was at Miss Sarah Jane Naphia's house. He did not get out of the buggy but called her out to the yard gate and asked her if she "had a mind to marry." She said that she did not, and so he drove about a mile further down the road to Miss Nannie Kidd's house. He called her out to the buggy just as he had done with Miss Sarah but must not have been quite as abrupt as it seemed to pay off. He said to her, "Nannie, I have got to go to Shores. I will be back by here about three o'clock. If you have a mind to marry, you be sitting on the porch at that time, and I will stop." She was sitting out there knitting when he came, and so he stopped. I suppose that they made all plans then as they were married a few days later. I tried to tease her about the courtship after he died. She said it wasn't exactly like what I have just written but mighty close to it. He lived about seventeen years after that, and I have never known a more devoted couple young or old. If he wanted something, he would holler for her like he was going to knock her head off, and in a few minutes, he would be petting her up. And she was devoted to him, and no one could have made him a better wife. She certainly looked after his good in his old age. Captain Anderson was a carpenter and a good one in his day. Many old houses in and around Fork Union are still standing that he built. One is the old C.G. Snead house on Route 6 just before you cross the creek as you enter Fork Union from the north. He was up on a house one day and called to one of his workmen on ground and said to him, "Measure that piece of timber down there and measure it correctly." The men did so and said to him, "It is four feet six inches and a half and a quarter and one eighth and another durned little dot. I don't know what that is." Mr. Anderson said, "That will do. Send it up here." JAKE MOON AND THE RAILS Captain Anderson had a large farm. He had a neighbor, Jake Moon, who was a bachelor and lived in a log cabin on a little place adjoining Anderson's farm. Jake worked for him quite a lot on the Anderson farm. All the fences at that time were made out of wooden rails as wire fencing was unknown. Captain Anderson wanted some rails split, and as the timber he wanted them made out of was near Jake's property, he made a bargain with Jake to split him some rails. Jake was to keep count and would be paid accordingly. The price was forty cents per hundred, which was the regular price then. Jake was a good worker and honest but lacking a little upstairs. Jake would get together what little money he could every Saturday morning and go to Scottsville to get his groceries and whatever else he had to have. He usually had a basket of eggs and maybe an old hen or two. On this particular Saturday morning before daybreak, someone knocked on Mr. Anderson's door and awakened him. He asked who it was. "Jake," was the reply. "What do you want at this time of night, Jake?" "I want a settlement for splitting rails." Captain Anderson was always ready to pay his bills and so he got up, lit the lamp, and put on some clothes. Then he asked Jake how may rails he had split. His reply was, "Twenty-eight." "Do what?" "I split twenty-eight." By that time, Captain Anderson had lost his temper, and he said to Jake, "You clear out from here, sir, and don't ever come back," which he did not mean, and Jake knew it. He looked after Jake and saw that he did not suffer for anything for as long as he lived. When Jake died, Captain Anderson made his coffin, and he was buried in the Anderson cemetery. Jake thought the sun rose and set in Captain Anderson's son, D. Wiley Anderson (1864-1940). But D. Wiley Anderson used to tease Jake and ask him how much was the total cost of twenty-eight rails at 40 cents per hundred. Jake's answer was, "Oh, God, that is hard to figure." D. Wiley was living in Richmond at that time and would bring Jake a lot of old clothes. Jake was so proud of those clothes from D. Wiley! HIS WORD Captain Anderson, as everyone called him, at one time endorsed a note for his brother-in-law and had to pay it. He never signed another note. A great saying of his was, "By gum, my word is my bond, sir. Take it or leave it." That was exactly what he meant, and he lived up to it always. THE BRIDGE A public road, which was supposed to be kept up by the county, went through Captain Anderson's farm for about a mile. It also crossed Hardware River on his farm. When I was a boy, there was no bridge at his place. To get to Scottsville, which was the nearest store or post office, you either had to ford the river or go several miles further to cross on a bridge. The only way they had then to get any mail or to send any mail was to go to the Scottsville post office regardless of distance. Captain Anderson tried for many years to get the county to build a bridge but had no success, and so in his old age, he took his son, Phillip, who lived on the farm, and his farm hands and built a bridge. The Fluvanna County Board of Supervisors met at Palmyra once a month on Monday. Captain Anderson's wife had a nephew, who lived near Palmyra, named Elijah Tillman. One Sunday afternoon after he had finished the bridge, Captain Anderson hitched his horse to the buggy, and he and his grandson (Jack) went down to Mr. Tillman's and spent the night. The next morning, they went on to Palmyra to report to the Board what he had done. Mr. Tillman went with him. His son-in-law and Jack have both told me the same story about what took place at that meeting. Captain Anderson said, "Gentleman, I have been trying to get you to build a bridge at my place for a long time, but you would not do it, so I have built one. It will not do me much good as I am getting too old to use it much longer, but my children and grandchildren and all those other people up that way do need it, and I know that it will be a great help to them. It cost so many dollars and cents. Here is a statement of what it cost. If you feel like helping me out with some of it, I would be glad, but it is paid for. 'Lijah, get your hat." The Chairman of the Board said, "Wait, Mr. Anderson, and let's talk this over." Captain Anderson said, "I've had my say-so, Sir. You all know where I live. 'Lijah, get your hat and let's go." His son, Phil, told me that they sent him a check for what he actually paid out but nothing for their labor. The bridge has been rebuilt several times, but the one that he built lasted longer than any up to the present one. There is a very good bridge there now, and it was one of a very few that withstood the great flood of 1969 which will long be remembered. THE OIL LAMP I don't remember the time when they did not have oil lamps, but they did come into use not long before my time. The only light they had before then was from candles or what they got from the fireplace. My father-in-law (Philip Anderson) told me this about his father (John B. Anderson). He had a close neighbor and a very dear friend, Captain Jim Hughes. Once Capt. Hughes bought two lamps at a sale. He stopped by to show them to his friend. When Captain Anderson saw him coming towards the house with them, he called to him and said, "You stop right where you are, Jim. You know that you are welcome to my house any time that you want to come, but you are not going to bring those things into my house and burn up everything that I've got." I am sure that just as soon as he found out that, if handled properly, they did not burn up everything you had, and he had them. When I knew him, he was always ready for anything that meant progress. He had the second wire fence around here. He was driving along the road one day and saw Ed Tillman putting up a wire fence for somebody. Captain Anderson stopped to look at the wire fence and decided that it was a good thing. So he made a bargain with Ed right then to put up one for him just as soon as he could get the wire and Phil could get the posts. Captain Anderson had one of the first grain binders around here. He saw one working somewhere and saw at once that it was a great labor saver, and so he bought one at once. DR. STINSON AND THE AUTOMOBILE Dr. Stinson bought the first automobile anywhere close around here. It was a little red Maxwell. It made about as much noise as a threshing machine and made all of about twelve miles per hour. Maybe fifteen miles per hour on a good road, which we did not have in those days. Old man, Pleasant (Pleas) Harding had a horse that really could move. The horse was named Wray. Pleas lived about four or five miles or more from Scottsville. One day Pleas left Scottsville driving Wray hitched to a buggy. Dr. Stinson left right behind him in his car going down the same road. Wray heard that noise behind him, and I suppose that he decided that the road was all his and so he took off. Doc Stinson said that he never got close enough to him in that four miles to even try to pass. Something like that on the road was something horses just could not understand, and almost all the horses were scared half to death of them. Believe it or not, but there was a law passed about that time which said that if you were driving a car and met a team, you must stop, and if the team seemed scared, you must get out and lead it by the car. Doc drove by Captain Anderson's place one day and ran over one of his lambs and killed it. The first time that they met after that incident, Capt. Anderson said to the doctor, "Stinson, by gum, sir, you can come to my place whenever you please so long as you drive a horse, but don't you ever bring that automobile out there again. I am not going to let you scare all of my stock to death and kill all of my sheep." They met in Scottsville soon after that, and Doc asked him to take a ride with him in his car. Capt. Anderson hesitated for awhile but finally consented. When they got back, he said, "Stinson, you bring this thing out to my place any time that you want to. By gum, sir, if I was a bit younger, I would get myself one!" He always pronounced automobile just as it is spelled, putting a lot of emphasis on the "I". MAKING THE WAGON Fannie (Fannie Anderson Sadler) wants me to write about something that happened between her and her two brothers, Jack and Morris, and their grandpa. I am going to write it as near like Fannie told it to me as possible, and since Fannie was in this family memory and also was the oldest child and probably the ringleader, I am sure that is just like it happened. Captain Anderson had a workshop near the house, and in it he had a very large box with a top on it in which he kept his carpenter's table. He also kept some lumber in the shop, and he would go there and work whenever he felt like it. At this time, he had some tobacco hanging up in the loft curing out. The children had found four small iron wheels somewhere and so they decided to go into Grandpa's shop and make a wagon. The shop door was always kept locked, but the shop had no floor, and so the lock did not worry them one bit. They just scratched a hole under the door and crawled in and went to work. I am sure that Grandpa heard them knocking and went in to see what was going on. Anyway, one of them saw him coming but too late for them all to escape. As Morris was the smallest, the others put him in the toolbox and shut the lid. Jack hid up in the loft. Fannie could not find a place to hide and so she had to face the music. Or that is, face Grandpa. He came in, and the following conversation took place between them: "What are you doing in here!" "Helping Jack and Morris make a wagon." "How did you get in here?" "Crawled under the door." "Where is Jack?" "Up in the loft behind the tobacco." "You come down from up there, sir. Where is Morris? "He is in the toolbox." Grandpa raised the lid and said to him, "You come out from there, sir." After Grandpa Anderson had given them all a good scolding and told them to clear out and never come back to his shop, he got out his tools and some lumber and made them a good wagon. But before they had gotten far from the shop, he called them back and let them help him make it. THE FLY FAN When I was young, the doctors all said that if we did not have plenty of flies around to take away the filth, we would all die, and so there was no such thing as a fly screen. When we got ready to eat, most people would send someone to get a bush, and someone would shake it over the table to keep the flies away while the others ate. Some people had fly fans. That was a light wooden frame on which was pasted paper and hung a few inches below the frame. This was hinged up to the ceiling over the dining table. It then had a string tied to it and as someone pulled the string, the fan would swing back and forth to scare the flies away. Captain Anderson had such a fan, and it was supposed to be Fannie's job to pull the string. The following is her story, but it sounds so much like her that I am willing to bet that it is true: Fannie soon learned that if she gave the string a hard pull at the right time when Grandpa was saying grace, the paper at the bottom of the fan would slap him in the face. Then Grandpa would say, "Fannie, give me that string." Grandpa knew all the time what it was all about, and he would just smile. I don't blame Fannie one bit. They would always make some of us young ones do it, and we would have to stand at one end of the table and pull that string back and forth all the time that the others were eating and wonder if they would ever finish or if they were going to leave us any food at all. THE ACCORDION My mother-in-law had a brother named Edd Sadler, who was a carpenter and considered working for Captain Anderson a good deal. Edd also loved music and had one of the best bass voices I have ever heard. Mrs. Anderson had an accordion which she could play well. Captain Anderson thought that he could play it, but I am not sure that anyone else agreed with him about that. One afternoon after they had stopped work for the day, he got out the accordion and started to play for Edd. He stopped in a little while, and the following conversation took place: "Edd, do you know what that was?" "Yes, sir." "What was it?" "That was 'Nellie Grey'." "That is not so, sir. It was 'How Firm a Foundation.'" PRAYER Captain Anderson loved to read the Bible. Fannie has one now that he got from my father when he was a colporteur. It has the largest print of any that I ever saw so Captain Anderson could read it as he was an old man. Passage after passage in it are marked in his own handwriting. He always had family worship and could pray a good prayer at home or in public and was always ready and willing to do so when called upon�with one exception. Elijah Tillman, who I have mentioned before, told this on him. They were members of the same church. One time, the preacher called on Brother Anderson to lead in prayer. He did not like the preacher and probably had not slept well the night before, and so he came out with this: "Pray yourself, sir. You are paid to do so." THE FERTILIZER BILL When I was young, there was very little fertilizer used compared to what is used today. Today most of it is sowed on the land broadcast. The rest is put up in eighty-pound bags. Then it was all sold in two hundred-pound sacks. You could not go to the store and buy what you needed as you can today. The fertilizer companies had agents over the country, who could see the farmers and take orders for what they needed until they got enough orders to make a carload, which was from thirty to forty tons. When the car came, the farmers would unload it and haul it home in their wagons. There were no trucks then. My father, William Sadler, was such an agent for awhile and sold Captain Anderson some fertilizer. He knew well that the money was good, and so he did not go to collect it at once. Philip Anderson met Father one day and said to him, "Willie, I am sure that Pa can't last much longer, and I know that he owes you for some fertilizer. Of course, you know that you will get your money, but if he should die first, it might take some time so I advise you to see him and get it settled now." Father had to go to Scottsville the next day, I think, and since it was not much out of his way, he went by Captain Anderson's place. Just as soon as he had gone in, and they had greeted each other, Captain Anderson said to his wife, "Nannie, get my check book. I owe Willie so many dollars and so many cents for fertilizer, and I want to pay him." He knew exactly how much it was. Father talked to him for awhile and then went on to Scottsville and attended to some business. Before he got back home, he heard that Captain Anderson had died. HIS BURIAL Captain Anderson's burial was the first Masonic burial I ever attended, and it made quite an impression on me. He had a Masonic charm made from a ten-dollar gold piece which his son, D. Wiley Anderson, had given him. He always wore it on his watch chain. I never saw him without it. Captain Anderson gave it with the watch and chain to his son, Phillip, who was my father-in-law, but was not a Mason. Several years later, Phillip gave them to me. "This charm was one of my father's most prized possessions. He loved it, and he loved Masonry. I am very sorry that I did not follow in his footsteps, but I am not a Mason and so I cannot wear it. So I am giving them to you with the hope that you make use of it." I put in my application to the Masons a few days later and was accepted. So directly I was persuaded to become a Mason by a man, who was not a Mason. Indirectly it was through the influence of Captain John B. Anderson. He not only loved Masonry, but he lived Masonry and practiced it all of his dealings with his fellow man: "By gum, sir, my word is my bond. Take it or leave it." Captain John B. Anderson was born on December 1, 1819. Died October 17, 1911. Nearly 93. All four of Phillip's sons became Masons and many more of Captain John B. Anderson's grandsons also became Masons.

1) "Family Record of Nathan B. Anderson As Found in the Bible of His Eldest son, John B. Anderson", (Images # JPW007-JPW010, Jean Williamson Collection, Scottsville Museum Digital Archives. 2) Sadler, Thomas Cleveland, "Memories Of Bygone Days", privately published, 1971. (Images #JPW029-JPW055, Jean Williamson Collection, Scottsville Museum Digital Archives). 3) Frazer, Susan Hume, "D. Wiley Anderson, Virginia Architect (1864-1940)"; Disertation submitted for partial fulfillment of Doctor of Philosophy degree for Hume at Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU), 1982; Chaper 2, pp 10-17; UMI Microfilm 3023400, Ann Arbor, MI. 4) Van Allen, Keith, "Captain John B. Anderson, A Short Biography and Summary Regarding His Civil War Sword." (Images #JPW001-JPW004, Jean Williamson Collection, Scottsville Museum Digital Archives). 5) Photographs of John B. Anderson's Civil War Sword, (Image # CG005cdCG2019 and CG008cdCG2019, Scottsville Museum Digital Archives). 6) John B. Anderson and Mary E. Morris Marriage Record, 16 May 1843, Albemarle Co., VA; Ancestry.com, Virginia, Compiled Marriages 1740-1850. 7) 1850 U.S Census, Fluvanna County, Virginia, 29 July 1850; Ancestry.com, Virginia; Roll: M432_944, Page: 8A; Image: 21. 8) 1860 U.S. Census, St. Annes Parish, Albemarle County, Virginia; Archive Collection No. T1132; Roll: 5; Page 93; Line 21; Enumeration Date: 09 Jun. 1960. 9) 1900 U.S. Census, Cunningham, Fluvanna County, Virginia, John B. Anderson; Page: 9; Enumeration District: 0073; Ancestry.com.

Copyright © 2022 by Scottsville Museum |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

||||