|

|

|

| |

A hogshead replica, built by Jeff Falls for Scottsville's Canal Basin Square in Summer 2018.

|

|

Name: Let's Roll a Hogshead! Date: 2018 Image Number: CG01cdCG2019 A picturesque phase of tobacco marketing in the Colonial and Early National period in Virginia was the practice

of rolling the hogshead of tobacco from the plantation to the place of inspection and sale. Transportation of tobacco in this

manner was considered by William Tatham as "peculiar to the Virginia era" in a book he authored in 1800 entitled, "An Historical and

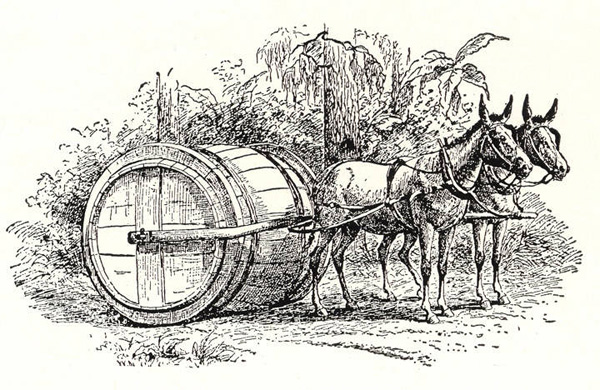

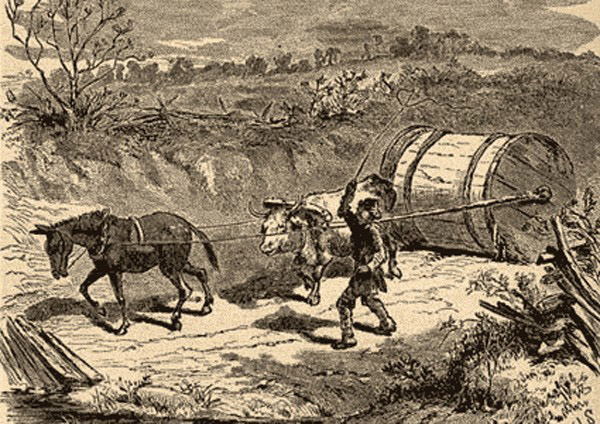

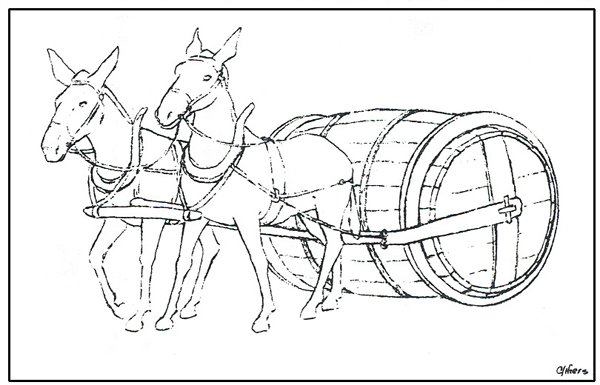

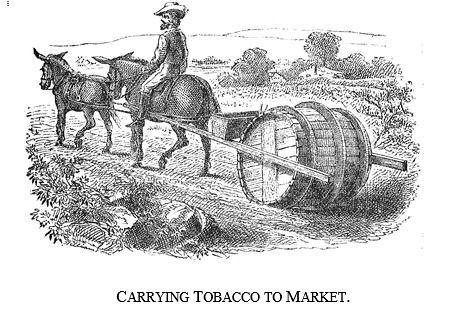

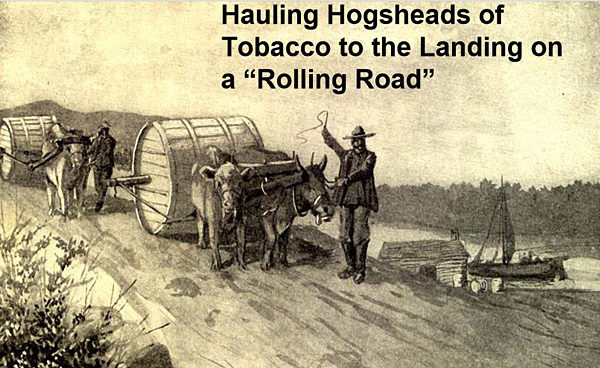

Practical Essay on the Culture and Commerce of Tobacco."  T1: Two horses in series with the drover using a whip and riding the second horse.(Tatham, p.55) Much of Virginia's history is the history of hogsheads. These were large barrels about 4 feet high and 4 feet in diameter and weighed about 1000 pounds, half a ton, when packed with tobacco. Shown above is a hogshead replica with a rig for rolling it as created by Jeff Falls and on display at Scottsville's Canal Basin Square. Dictionaries are not sure why they were called hogsheads, but it may come from European "oxhead" barrels which were branded with an ox head. (See "Tobacco Barrels: Hogsheads" on NCpedia). By 1700, tobacco was King in Virginia and North Carolina, and it was the money crop. The tobacco growers' receipts at the inspection warehouses were used as money, and goods were valued in pounds of tobacco. Even today, the Tobacco Era is still not entirely over. The major tobacco growing district in Virginia and North Carolina into the 1860's was the Piedmont, between the Blue Ridge Mountains on the west and the fall line on the east. (See map in Robert, p. 16; Giese, p. 5). From north to south, the rivers in this district were the Rappahannock, James, Appomattox, Staunton, and Dan, flowing east to the fall line market towns of Fredericksburg, Richmond, Petersburg, and Weldon. Eventually, all of these rivers were "improved" for boats carrying tobacco hogsheads down to these towns, but it took a while. Kulikoff, in Tobacco and Slaves, says that it was not until the 1720's and 1730's that the more prosperous planters in the Chesapeake region enjoyed the luxury of knives and forks (Kulikoff, p. 180). It took a little longer than that for the technology of transportation to reach what was to become Virginia's tobacco district. There was no point in growing tobacco if it could not be safely carried to market without damaging the tobacco. Boats Designed To Carry Tobacco Hogsheads: Robert Rose's Double Canoe The breakthrough came in 1749 when a planter near Lynchburg invented a method to carry hogsheads down the James River to Richmond. The Reverend Robert Rose in Nelson County on the Tye River invented the idea of lashing two dugout canoes together like a catamaran so they could carry tobacco hogsheads without turning over. In March 1749, he launched his first (probably three) catamarans, known as "Tobacco Canoes," at New Market (now called Norwood), at the mouth of the Tye 36 miles down the James from Lynchburg. There was probably a variety of canoe lengths. The catamarans were probably about 8 feet wide (for two dugouts together) and 50 to 60 feet long and could carry 5 to 10 hogsheads. Fortunately for the Piedmont planters, the James was then reasonably navigable in its natural state, from the Lynchburg area down to the falls in Richmond. In Richmond, the hogsheads were unloaded and dugouts separated so they could separately be poled back upriver for another load, each by a crew of two. Rose's novel method was used for at least 22 years, until a record flood in 1771 washed away many of his dugouts. We'd like to see one! Are any of them awaiting rediscovery, buried in a mud bank or on the river bottom? Were any washed down into the tidewater James? Can his dugouts, shaped by the white man's tools, still be distinguished from Native American ones shaped by fire? Was Rose's invention used on any other rivers? For the latest research and speculation about Rose's invention, see Robert J Faught's book, The Belle of Rose Isle. (For flood info, see Cabell's diary, Percy, p. 8.) The James River Batteau After the great flood of 1771, Anthony and Benjamin Rucker in Amherst County invented a new style of boat especially designed to carry tobacco hogsheads. Thomas Jefferson noted in his diary on April 29, 1775, that "Rucker's battoe is 50.f. long, 4.f. wide in the bottom & 6.f. at top. She carries 11. Hhds & draws 13 1/2 l. water." (Betts, p. 257) Was this the date of the first launching? Was Jefferson there himself? He didn't say. The "fact" that Jefferson was there seems to come from an article in the August 17, 1821, Lynchburg Press (Giese, note 339) which we have not seen. By that time, Virginia had sawmills, and so these boats were made of sawn planks. "Bateau" is French for boat, so there are many types of bateaux all over the world. We call our type the "James River Batteau" to distinguish it from variant styles, including those on other Virginia rivers such as the Rappahannock. We spell it with two t's because that was the usual educated spelling in Virginia during the batteau era. A search of the Virginia Acts of Assembly from 1803 to 1900, and Hening's Statues from 1792 to 1807, found 41 spellings with two t's and none with one t. (VC&NS Sweep, Spring 2015). Jefferson spelled it "battoe." The plural is batteaux or batteaus. Thew were also known as "Tobacco Boats" and "Market Boats." Each was about 30 to 50 (and later 60) feet long, and carried about 5 to 8 hogsheads (Robert, p 55) or more? The Ruckers patented their invention in 1821, but the US patent office burned down, and no copy of the patent has ever been found, so we don't know the details. Could a copy be in county records somewhere in Virginia, Tennessee, or elsewhere? Little was known about James River Batteaux until a number of them were excavated in Richmond's Great Basin in 1983-85. In 1984, famed banjoist and historian, Joe Ayers (see more about Joe Ayers on the Internet) built a replica and founded the annual James River Batteau Festival, which is still running today. Because of this, batteau replicas are on display all over Virginia. A batteauman is even on Richmond's new city flag! (See The James River Batteau Festival Trail atlas) The Gundalow We know now that there was another type of boat used on the James to carry tobacco, called the "Gundalow." (Percy (p. 9) citing Gallatin 1808 (p. 10)) says that the batteaux descended the river in groups of three, and in Richmond, two of them were taken apart and sold for lumber, and the combined crews poled the remaining batteau back upriver with city goods. We believe now that he was mistaken that the two boats sold for lumber were not batteaux but square-ended flat-bottom boats called gundalows, built like ferry boats of squared lumber which could be sold as building materials. The batteaux we excavated in Richmond's canal basin had tapered boards, not suitable for building. And why make a boat pointed at the ends, if it were making only a downstream trip? We found one boat in the Richmond dig which was probably a gundalow. It dates from 1800 when the canal basin was being dug, because it had been turned upside down to make a bridge over a gully. Gundalows also made one-way voyages on the Shenandoah, Potomac, and Holston rivers. You can still see gundalow wood in buildings in Harper's Ferry on the Shenandoah. Is there gundalow wood in any of Richmond's buildings? There were gundalows on the upper Rivanna in Jefferson's time. He said that he boated hogsheads down the Rivanna to Milton on flat-bottomed boats, where they were transferred to larger boats, probably batteaux. (Betts, p. 341) There were probably gundalows (flat-bottoms) on other Virginia rivers, so we need to keep an eye out on all of them for buildings made of old boat wood. It was the tobacco trade which greatly encouraged the development of river navigation improvements in the Virginia tobacco region. The James was improved for batteau navigation in the 1780's. This was replaced by the 200-mile long James River & Kanawha Canal for mule-drawn canal boats; and that was replaced by the C&O Railway, still very active today, laid on the canal towpath. All carried hogsheads to market. The Rappahannock, Appomattox, Staunton, and Dan were also improved for batteaux carrying hogsheads (see VCNS atlases on these rivers for details) Some sailing ships were especially designed to carry hogsheads across the Atlantic (Middleton, p. 129). And beginning in 1961, the Southern Railway even had special Tobacco Hogshead Cars for carrying hogsheads. They were 84 feet long (as long as a canal freight boat, but half as wide), carried 100 hogsheads, and had a peculiar shape of roof with round skylights to illuminate the interior. (For photos, search the web for Southern Tobacco Hogshead Car.) Prizing On the plantations, farmers built hogsheads and prized (squeezed) their tobacco crops into them. Tobacco hogsheads were large wooden barrels each weighing about half a ton. Every year, Virginians packed and sent to market about 30 to 50 thousand hogsheads. (Robert, p. 132) In tobacco rolling days, each farmer probably had his own device for 'prizing' the tobacco crop into hogsheads, packing it tight. Giese's Tobacco Cultivation in Virginia devotes six pages (p. 38-43) to descriptions and woodcuts of prizing machines. Most of them had long, strong levers attached to a tree or to a post firmly set in the ground; some had wooden or iron screws which were turned to compress the tobacco. The prizing was generally done under a shed roof or in a 'prize barn.' Elk Hill Farm in Nelson County still has its prize barn, complete with a screw prize, both thought to date to 1790-1810 (Pugh). Jefferson's Poplar Forest had a prize barn. The location is known, but it is long gone. Are there any early prizing machines waiting for rediscovery in old prize barns? In later years, some tobacco was wagoned to towns and prized there in factories. South Boston, on the Dan River, has a building called "The Prizery," restored for use as a theater. It is on the site of the W. A. Willingham Co. prizery and might have screw prize machines on display; see prizery@mac.com (From Jennifer Bryant, South Boston-Halifax County Museum). The Sweeney Prizery is in Appomatox. Rolling Roads to Waterways But how did the farmers' hogsheads get down to market or to the river landings? Little is known about them. We know that some were carried in wagons, probably two per wagon. But many were rolled, one at a time, on "rolling roads." Rolling probably declined in the 1830's, but Robert says "as late as 1850 a rare tobacco roller might be seen on his way to Petersburg." (Robert, p. 53-54, citing Phillips, p. 143) Has anyone tried to map out possible rolling roads? But how could a road meandering down a stream valley to a bridge or ferry - such as Scottsville's - avoid fords? Tobacco Hogsheads By 1783, Virginia put limits on the size of tobacco hogsheads because freight charges, inspection fees, taxes, and warehouse fees were calculated by the hogshead. Cheats tried to make their hogsheads larger than others to save money. (Robert, p. 235-239) The official limits were:

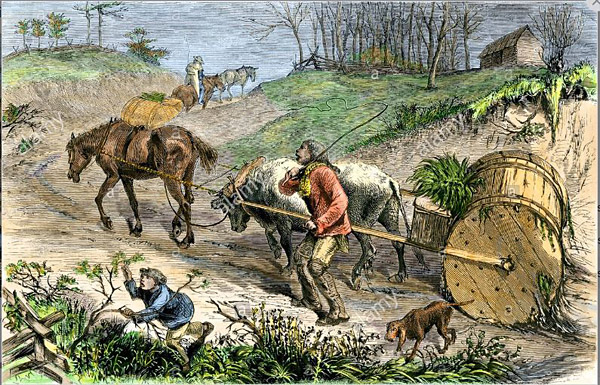

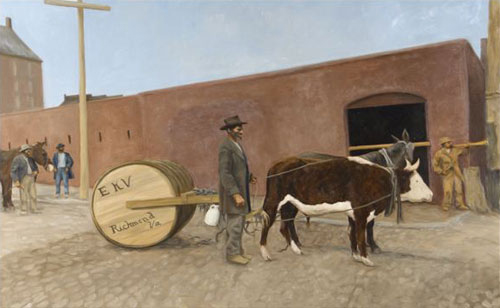

These were the maximum allowable dimensions, so hogsheads could legally be smaller than this. And coopers and inspectors probably ignored the legal limits at times, so some may have been larger. The 1796-1822 dimensions agree with a note by Jefferson in his Farm Book, p. 114. These are the legal dimensions, but how big were the actual hogsheads from the early 1800's? We know of one early hogshead, now in the Tobacco Farm Life Museum of Virginia in South Hill, the only tobacco farm life museum in Virginia. Their hogshead is 43 1/2 inches high, 33 1/2 inches in diameter at the head, and 39 inches in diameter at its belly. It has staves of chestnut and is bound by hoops of hickory. The donor dated it at 1790-1800. Another hogshead is displayed in the lower level at Jefferson's Poplar Forest. It is 4 feet high, 28 1/2 inches at the head, and is banded by flat iron hoops. Gail Pond, collections manager at Poplar Forest, reports that it is an authentic 19th century Maryland hogshead from Carroll County. Can't hogsheads and barrels be dated by the type of hoops? When did these flat iron hoops appear? In 1796, Jefferson mentions "hoop iron" in his Farm Book, p. 433. Colonial Williamsburg has a hogshead on display, which is 4 ft. high and 31 inches at the head, measured by Diane Easley. It is one of the world's newest old tobacco hogsheads because it was made not long ago by Jonathan Hallman, Colonial Williamsburg's cooper! Duke Homestead also has a hogshead. Some years ago William Hoffman saw a hogshead rig with fellies pulled by oxen at Westmoreland State Park, but the park staff doesn't remember it. Glen and Barbara Shrewsbury have a hogshead. Where from? Most hogsheads in the early days were shipped to Europe. Are any still there, intact enough to measure? Even a single stave could tell us the height of the hogshead and if it had wooden or iron hoops. The head of each hogshead was branded to identify the owner. Thomas Jefferson's hogsheads at Poplar Forest, were labeled "PFT I" - "Poplar Forest Thomas Jefferson." (Giese, p. 107; back then a J looked like an I.) Does an original branded head board survive anywhere? Mike Prieto, of Barrel-Art.com, makes interesting furniture out of barrel staves from Europe and tells us that he will look for hogsheads on his next trip. The Rucker batteau must have been designed to fit these 4 foot hogsheads. Each batteau had walkboards the length of the hull, along each side of the boat on top of the ribs, to roll the hogsheads along. So how much room did these boats have between the sides for rolling hogsheads? We found that the "Hearth Boat", excavated in the Great Basin, had five feet of clearance between the sides; Boat #3 had at least 4 1/2 feet - so both are just right for carrying 4 foot hogsheads. When traveling down river, loaded with hogsheads, the walkboards were covered up by the hogsheads, but they were not needed going down river. They were only needed for poling upriver, and that's when they were not covered with hogsheads. Even today, hogsheads are used to ship tobacco. In the 1950's, the old oak hogsheads were replaced by plywood ones with 48" (4 foot) staves and 48" in diameter. The staves are straight and are hinged to each other so when empty, the hogshead can be folded flat. The staves are straight, not bowed, so there is no belly. As of this writing, Phillip Morris still uses hogsheads because their equipment for shipping and handling tobacco is designed for hogsheads. After the hogsheads are emptied, they are inspected and restored to working condition to be used again. Those which can't be fully restored are discarded or are repaired cosmetically and donated to museums. The weight of a full hogshead varied from about half a ton (1,000 pounds) in the 1790's to about 1,200 pounds after 1810, or even heavier according to some sources. The hogsheads were wagoned or rolled from the farm to tobacco inspection stations, where they were broken open and inspected; for those that passed, the farmer received a "Tobacco Note" which was used as currency. At the beginning of the 1800's, there were 72 official inspection warehouses in Virginia, most of them in the vicinity of Richmond, Lynchburg, and Petersburg. (For more about the location of warehouses, see Robert, p. 77-79. This is a good subject for further study!) At times, these warehouses were the venue for public meetings, with the orator standing on top of an empty hogshead. On one occasion, the barrel head fell in and so did the speaker. He was so embarrassed that he stayed down in the hogshead until the crowd left. (Robert, p. 80 citing Christian, Lynchburg and its People, p. 106.) After inspection, the hogsheads were put back together and shipped to market. Those that didn't pass were supposed to be burned, along with the tobacco. In the early days, almost all of the hogsheads were shipped abroad. In time, more and more went to local factories producing pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and snuff. Rolling Tobacco Hogsheads Tobacco hogsheads were made by coopers on the tobacco plantations. Those to be rolled were built tightly to be as waterproof as possible, because water could ruin the tobacco. A tight hogshead also must have had an advantage while being boated down the whitewater James River in a double dugout or a batteau, or on a wooden ship crossing the Atlantic. "Dunked" (waterlogged) hogsheads were supposed to be burned or thrown out. Hogsheads being rolled needed extra protection similar to car tires, at each end and to prevent the staves from being damaged. When Hickory hoops were wrapped around the hogshead, it was known as "rolling in hoops." And when a series of curved pieces of wood were pegged to the circumference like a car tire, it was known as "rolling in fellies" (Robert, p. 53; Tatham, p. 58). Fellies (or Fellows) were more durable and heavier than hoops. An old woodcut (T4) below clearly shows "Fellies" like a tire, made of curved wood pieces. It became traditional that fellies and shafts were given to the auctioneer or inspector (Percy, p. 3).  T4: Two mules pulling a rolling hogshead in 'fellies', a hickory hoop wrapped around the hogshead.

T4: Two mules pulling a rolling hogshead in 'fellies', a hickory hoop wrapped around the hogshead.Illustrations of Rolling Hogsheads Hogshead rolling must have been considered romantic because the old magazines carried dramatic illustrations of rolling. Much of what we know about rolling is from these old woodcuts. So far, 11 woodcuts have been found. They show a variety of rigs and a variety of animals, horses, or mules, or oxen, or a combination. We have give "T" (Tobacco) numbers to these old woodcuts so they can be discussed and compared. Are they all accurate? We've learned not to absolutely trust the details in old woodcuts! Most of these images (but not always sharp versions) come up on a Bing search for "hogshead rolling." We need to keep searching for the original or sharpest versions (and discover the articles accompanying them). The sharpest versions will be posted on the Scottsville Museum's archive section of its web site, https://smuseum.avenue.org/ . T1. Two horses in series, with the drover with a whip riding the second horse. Original: An Historical and Practical Essay on the Culture and Commerce of Tobacco, by William Tatham, London, 1800, opposite p. 55. Facsimile in Herndon. Americanhistory.si.edu . See second image (T1) above. T2. This is T1, reversed with a redrawn hogshead, in Percy, 1963, p. 3. T3. Below: An ox and a horse, in series. Drover with a whip beside the ox. Reversed, and very small, in Percy, 1963, p.1. See: YanceyFamilyGenealogy.org, pinterest.com.  T4. Two mules in tandem with a wagon-tongue rig; shows rolling in fellies. See third image (T4) above. T5. Below:Two oxen in tandem, with a wagon-tongue rig. See Tobaccohogshead.gif at broyhill.org.  T6. Below: Two oxen in tandem with a man holding a rope for a brake. This is a flat waterside scene, and so perhaps there was no need to have the harness used as a brake? "Hogshead Containing Tobacco on a Rolling Road" from David W. Eaton, Historical Atlas of Westmoreland County, Dietz Press, Richmond, 1942, p. 3. From Milaminvirginia.com/links/glossary/hogshead.html .  T7. Below: Line drawing of T4. Drawing signed "Cfothers" (sp?). Where from?  T8. Below: Two mules in series with the drover riding the second mule. From Tobacco: Its History, Varieties, Culture, Manufacture, and Commerce, by E.R. Billings, p. 47. E-book from Colonial Williamsburg, www.gutenberg.org .  T9. Below: Ox and horse in series and drover with a whip beside the ox. Probably derived from T3. Drawing by Sheppard. www.alamy.com .  T10. Below: Two oxen in tandem. Hogshead is marked EKV. Pinsdaddy.com .  T11. Below: Two hogsheads pulled by mules, one in tandem and one singly. Drawing by Bernard Gutmann, 1997. In virginiahistoryseries.org/linked/unit&6 . This book is available online only and includes T1 and T6. (From Doug Macleod).  These woodcuts show a variety of details. It is thought that rolling rigs varied so much because they were homemade. Whether they were designed for rolling hills or flat country would also make a significant difference. Because it used a wagon tongue, Jeff Falls selected T5 as the basis for his replica rig for Scottsville's Canal Basin Square, and the Farm Museum in Ferrum built a rig similar to this one, adding a box. Such rigs, also used for wagons and coaches, were designed so that the animals could not only pull by way of a doubletree, but brake with a neck-yoke, holding back the hogshead when going downhill, without having the hogshead roll into their rumps (from Carol Carper). Such rigs would have been necessary for the rolling roads in the piedmont. Some of the woodcuts don't seem to show any way to brake, except by hand! Are these woodcuts accurate? Would they work? All hogsheads to be rolled had an axle through the center for attaching the rig. Did the cooper drill a hole in the middle of each head and drive a pole through the tobacco? We wondered how he could be sure to have the axle come out dead center, in the hole, at the far end! This mystery was solved by a statement in Mordecai (p. 334) that the axle was in two parts, each a couple of feet long. Each was separately driven through a hole in the hogshead head, into the packed mass of tobacco, which held it in place. (Of course, when we roll an empty hogshead for demonstrations, there will be no tobacco to hold the axles in place, so we would use a single long axle.) Let's have a Hogshead Rolling Festival! Credit for the first hogshead rolling in modern times goes to Ferrum College, in Franklin County, Virginia. Shown below is Rebecca Austin, the farm museum manager, who is helping a pair of oxen roll a tobacco hogshead. The first rolling was in 2002.  Hogshead Rolling at Ferrum College, VA. Photo courtesy of the Blue Ridge Institute

and Museum. Thanks to Jeff Falls of lineagelogistics.com, hogsheads are available for festivals. One would not like to roll a valuable antique hogshead, but his are modern plywood ones the same size, developed in the 1950's. Scottsville's Canal Basin Square has one of his hogsheads, which he equipped with an axle and rig for a pair of horses or mules. All it needs is that pair of animals. And thanks to the James River Batteau Festival, we have replica batteaux and crews to participate in such events. The Virginia Canal and Navigations Society even has a half-scale hogshead with a rig, built by Bill Jones, to be drawn by children around the grounds. He's thinking of building a half-size portable prizery to demonstrate squeezing tobacco into the hogsheads. Scottsville and other suitable places can put on an all-day Hogshead Rolling event. Down at the batteau landing, a hogshead can be rolled around the grounds from time to time all day, by a pair of draft animals, interpreted by the drover. Down at the boat landing, a batteau can be floating, already loaded with a hogshead, interpreted by the crew. The half-scale hogshead can be rolled around the grounds all day. Visitors can try packing tobacco (perhaps actually tree leaves) into hogsheads, using the half-scale prizery. The Virginia Canal and Navigations Society could put up its tent. Leave the hogshead on its rig all day, no need to dismantle it and roll it onto the batteau. Have the batteau there all day, no need to go downriver. The event could also be held where a river landing is not handy, as on the grounds of an historic home such as Patrick Henry's Red Hill or Thomas Jefferson's Poplar Forest. Just park the batteau on its trailer. Many thanks to our many friends including Carol Carper, Doug Harvey, Rebecca Austin, and Jeff Falls. William E. Trout, III

Volunteer Consulting Canal Detective Virginia Canal Museum 3806 S. Amherst Hwy Madison Heights VA 24572 Bill@vacanals.org Sources: Betts, E.M., Thomas Jefferson's Farm Book, University Press of VA, 1986. Bracy, Susan L., Life by the Roaring Roanoke: A History of Mecklenburg County, Virginia, Mecklenburg County Bicentennial Commission, 1977. Carper, Carol, our doomsteader. Mrs. Carper donated a pairs harness, for a pair of horses pulling a hogshead, to the Virginia Canal and Navigation Society for a future full-scale exhibit on hogshead rolling. Faught, Robert J., The Belle of Rose Isle: A Model-maker's Case Study of The Reverend Robert Rose's Double Dug-Out Canoe, Virginia Canals and Navigations Society, 2016. Giese, Ronald L., Tobacco Cultivation in Virginia, 1610-1863, Blackwell Press, 2016. Heimann, Robert K., Tobacco & Americans, McGraw-Hill, 1960. 276 pp., but no footnotes showing where the information came from. Herndon, G. Melvin, William Tatham and the Culture of Tobacco, University of Miami Press, 1969. Includes a reprint of Tatham, 1800. Inge, Reba G., Virginia Tobacco, The Golden Weed: A Brief History of Tobacco, Tobacco Farm Life Museum of Virginia, 1996, 28 pp. Kulikoff, Allan, Tobacco and Slaves: The Development of Southern Cultures in the Chesapeake, 1680-1800, University of North Carolina Press, 1986. Middleton, Arthur Pierce, Tobacco Coast: A Maritime History of Chesapeake Bay in the Colonial Era, The Mariners' Museum, 1953. Mordecai, Samuel, Richmond in By-Gone Days, 1860. Percy, Alfred, Tobacco Rolling Roads to Waterways: Tobacco, Incentive to Early Science, 34 pp., Percy Press, 1963. Pugh, Susan, Elk Hill farm building holds Nelson County's tobacco history, Lynchburg News and Advance, Oct. 13, 2010. Search for "Elk Hill Pugh". Robert, Joseph Clark, The Tobacco Kingdom: Plantation, Market, and Factory in Virginia and North Carolina, 1800-1860, Duke University Press, 1938; reprinted by Peter Smith, 1965. Tatham, William, An Historical and Practical Essay on the Culture and Commerce of Tobacco, London, 1800; reprinted in Herndon, 1969. Terrell, Bruce G., The James River Bateau: Tobacco Transport in Upland, Virginia, 1745-1840, Master's Thesis, Department of History, East Carolina University, 1988. Now online. Tobacco Institute, Tobacco: Deeply Rooted in America's Heritage, 1995. Trout, W.E., The James River Batteau Festival Trail, VC & NS. Includes the story of the Great Basin Excavation. Tobacco farm life museums in Virginia and the Carolinas: Tobacco Farm Life Museum of Virginia, 306 W. Main St., South Hill, VA 23970, 434-447-2851. Leonard Smith, Curator. Has an original hogshead. Tobacco Farm Life Museum, 709 N. Church St., Kenly, NC 27542, 919-284-3431. Melody Worthington, tobaccofarmlifemuseum.org Duke Homestead State Historic Site, 2828 Duke Homestead Rd., Durham, NC 27705, 919-477-5498. The Border Belt Farmers Museum, c/o Fairmont Chamber of Commerce, P.O. Box 214, Fairmont, NC 28340, 910-740-8645. Home Creek Living Historical Farm, 308 Home Creek Farm Rd., Pinnacle, NC 27043, 336-325-2298, homecreek@ncdcr.gov Northeast Park, 3421 Northeast Park Drive, Gibsonville, NC 27249, 336-375-6910. Thomas Marshburn, northeastpark@bellsouth.net South Carolina Tobacco Museum, 104 NE Front St., Mullins, SC 29574, 843-464-9583. Patrick Henry's Red Hill, www.RedHill.org, on the Roanoke River. Has no original hogsheads, but see the Patrick Henry Digital Library, www.patrickhenrylibrary.org See also https://www.ncpedia.org/tobacco/barrels, by Alison Holcomb of Duke Homestead. |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2019 by Scottsville Museum |

||||