|

|

|

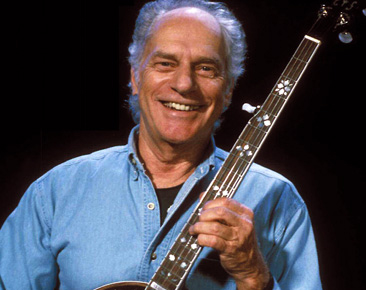

Name: Eddie Adcock  Eddie Adcock, Martha Adcock, and Tom Gray (L to R) In 2014, Eddie was awarded the 5th annual Steve Martin prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass Music. In addition to a lovely trophy, the prize included a cash-award of $50,000. Eddie thanked Steve Martin for what he's been doing for bluegrass: "When you try to thank Steve Martin for what he's doing for bluegrass lately, when it comes to this prize, he just says, 'It's for the artist.' I can't thank him enough, and his prize board, too, for their unanimous vote. I really appreciate the fact that there's someone out there, who knows the financial realities of bluegrass and the situation of so many of its musicians, and who's done all he could from every angle, including the bands and individuals by his shows and TV appearances. I bless Steve and his prize for lightening the load and chasing the blues. I thank God, and I thank Steve Martin - there's only one of each!" Eddie's work with his wife, Martha, has garnered three Grammy nominations as well as appearances at the Kennedy Center. Eddie was the first internationally acclaimed five-string bluegrass banjo player to play at Carnegie Hall. In 1996, Eddie was inducted into the Blue Grass Hall of Honor. To learn more about Eddie Adcock and his Scottsville beginnings, read: "I'm the Most Famous Poor Person You'll Ever Meet!" by Ruth Klippstein that was published in Scottsville Monthly in October 2016: "I'm the Most Famous Poor Person You'll Ever Meet" by Ruth Klippstein Eddie Adcock playing a guitar in the 1950's. Smiling and sincere, Eddie Adcock played more than half his recent show accompanied by Martha Adcock and Tom Gray at Victory Hall, with driving banjo and flights of fancy on the guitar, conjuring the glory days of the Country Gentlemen, before telling a favorite Scottsville memory to his enthusiastic fans. He and Rex Meyers, Eddie said, would jump from the hill behind Victory Theatre onto the roof, with straws they purchased at the dime store, and shoot peas at passersby in the street. They never knew what hit them, Eddie is still pleased to report; they never looked up. Eddie Adcock's life has stayed intertwined with Scottsville, where he lived until he was 16. He and Martha have been committed to the refurbishing of Victory Theatre and come yearly from their Tennessee home for this concert, which also gives them time to see family and friends. They were happy, after the show, to invite everyone to join them at the Tavern on the James. Scottsville looks good to them! Eddie was born here in 1938, one of seven siblings whose birth dates span more than twenty years. He lived his first seven years on Howardsville Road about three miles west of town. Then his father hand-built a house near Jefferson Mill Road, a place that became the source of the family's sustenance. "We lived off the farm," Eddie remembers, and, as a youngster, he did daily chores, helping with the cows, chickens, pigs, and gardens. "Everyone in my family was musical to a certain extent," Eddie now says--except, perhaps--well--his mother, who "sounded like a squeaky hinge." But they sang; brother Harvey played the harmonica, Frank played guitar, Bill took up fiddle, and sister Nancy had a beautiful voice. His other sister, Willie, sang all the time around the house, anywhere. The children were often in church or school choirs, as well. Eddie doesn't think of his family as a major influence in his life of music, though Bill gets special credit. Bill worked repairing, upholstering, and delivering furniture for Parr's, located in the three-story brick building now housing the James River Brewery. Harold Parr, who owned Chester--an estate on James River Road built in 1847 and now Chester Bed and Breakfast--would sometimes get instruments in trade, or Bill would be given an unused instrument when he brought furniture to people's houses. Gene Harding, a classmate of Eddie's, says he's heard Eddie tell that story at concerts. But what he recalls is Mrs. Mayo saying, "'Eddie, put that guitar down and do your homework.' "I don't know which version is true!" Gene says. "Mrs. Mayo recognized Eddie's talents and wanted to encourage him; she was always patient." Much of his musical training, Eddie says, came from listening. He learned guitar first, then mandolin, then tenor banjo. He was "relieved," he says, when his Scottsville friend, Joe Smith, showed him the proper way to hold the G chord, which was much easier than what he'd devised. Joe and his brother, Wes, were in a different band in town and "advanced, musically." Joe says his father played the fiddle and got him interested in music by teaching him guitar. He and his brother and a neighbor would play for dances and sometimes played with Eddie and Frank. Joe remembers they occasionally played on the street in Scottsville, especially near present-day Baine's Books and Coffee. One night someone opened a window above them and yelled, "'We're trying to sleep in here'-and they walked off playing and singing 'So Long, It's Been Good to Know You.'" One night, Joe says, he and Eddie walked home to Joe's, up Albevanna Spring Road, playing and singing all the way. Despite having help from Joe ("the one person he's taken advice from," says Martha), Eddie, throughout his career, has forged his own way and made his own sound. "It costs you to do music the way you want," he says, "and I'm the most famous poor person you'll ever meet." But eventually people caught onto his style and technique, and he says he's hearing popular musicians now playing as he did twenty years ago. Eddie went to first and second grade in the old primary school on Bird and Page, then to Scottsville High School into seventh grade. His asthma kept him back in first grade, and in third grade, his teacher, Mrs. Phillips, thought he should repeat, though he had passed all his work. He didn't question this until later, but being two grades behind his peers was a difficult challenge he says. Mrs. Mayo, his favorite teacher except for Miss Caldwell, was hard on him but, seeing his worth, helped him get as much out of school as he could. There was a small pavilion a type of bandshell, behind Scottsville High School, on the playground. It was roughly where the recycling dumpsters are now. Eddie and "anyone else musically inclined," according to Gene Harding, would play there informally during recess. Baxter and Pat Pitts remember this as a highlight. Gene says Frank, not as serious about music as Eddie was, was a "terrific player." Eddie forged a group called the James River Playboys. Eddie feels he couldn't always concentrate on school, due to his chores. His older siblings "got out as soon as they could." Wartime was a strain; the family worked hard to provide themselves fruit and vegetables, meat, milk, and flour--which they had ground at the Scottsville Mill on Main Street. "They bought only sugar, salt, and coffee," Eddie says. His father often made only $5 a week. His mother had a series of nervous breakdowns; his father, cancer. Eddie lived with an aunt for a while. He had a paper route for Grit and for The Daily Progress; he mowed lawns, including the Scottsville Cemetery, all with a push-mower. He didn't have a job at Victory Theatre but "helped out" there. Eddie, at 14 or 15, was raising a calf and feeling that he would like to be a farmer. He says he read about it, "got excited about farming. But music was burning in my soul." Occasionally, he'd earn pocket change--$4 or $5--by busking at Duke Johnson's Republic service station at the Main Street end of Valley Street. That was an odd-shaped lot on the east side of the road, he says, where two cars would fit, and four would make it 'plumb full.' He stood in front of the drink machine where folks would be sure to find him. His first professional music job was on WCHV, Charlottesville, where he played on a gospel show with Frank. He'd met the preacher at a tent meeting on the high school grounds. Then, in 1954, he heard Smokey Graves on the radio say he needed a five-string banjo player, "and farming went out the window." His mother sensibly noted that he played tenor banjo, not five-string, but Eddie knew he could learn. Without a phone, he wrote to Graves, who responded by inviting him to try out for the job. "I'll be there in two weeks," Eddie wrote, "there's some stuff I have to clear up around the farm." Eddie sold his calf and bought a new Gibson banjo at Stacy's Music in Charlottesville. "I stayed glued to the banjo and the clock. My finger bled. I got to where I thought I was good to fake the rest. Smokey understood I was a musician and thought I'd continue learning," and so Eddie was hired. He left home in 1954 to join the Blue Star Boys in Crewe, Virginia. His mother helped with the banjo payments, and when he started making $35 a week, he sent money back to her. "I lived in the YMCA in Crewe," Eddie says, "and later with a family." Besides giving him professional experience, this time also exposed Eddie to a deep degree of racial animosity he never knew in Scottsville. The band did regular radio shows and played for dances or concerts. Whenever shows didn't prevent him, he hitchhiked home to his mother's, usually two or three times a week. "When they came back to Victory Theater," Martha says, "he was a hero!" This is the period in Scottsville that Eddie remembers as the best. Three hundred and fifty people would fill Victory Theater for two shows a night, seeing the best acts in the country--Kate Smith, Flatt and Scruggs, Roy Acuff, Gene Autry. There was a guaranteed crowd for the music in Scottsville; acts never went to Charlottesville. "Victory Theater was poppin'!" "Scottsville," Eddie says, "when I was a kid, was so crowded you couldn't walk down the sidewalk on weekends. You had to step off into the street. There were horses and wagons filled with produce, as well as cars. Everyone was out. It was an expansive time, 'peacefully optimistic," Eddie recalls, through 1956; three or four years later, "it looked like a desert." But Eddie was off to broader horizons: a job with Mac Wiseman in 1955 and Bill Monroe in 1957. His most renowned group, the Country Gentlemen, was invited to play at Carnegie Hall in 1961; Eddie stayed with them until 1970. This group, through Eddie's determination to play music his own way, pushed the boundaries of bluegrass and broadened the appeal of its sound during the folk music explosion of the '60's. "I released all my insides, all my creativity, into the band," he says now. "I was ready to say something on my own-and that's where I made my mark." Throughout a wide-ranging career and many awards, including the Virginia governor's proclamation of June 14th, 1987, as the first "Eddie Adcock Day," Eddie treasures most not his fame but Martha Hearon. They met through music in 1973 and married in 1976. "This was my life completed," he says simply. Today after three dramatic, difficult deep brain stimulation surgeries to correct a tremor in his right hand, Eddie continues to play special concerts with Martha, be involved in various musical and other charities and educational efforts, and to run a recording studio. (L to R): Eddie Adcock, Martha (Hearon) Adcock, and Tom Gray At the October 5th concert at Victory Hall, Eddie and Martha, joined by former Country Gentleman, Tom Gray, on bass, played on the 6oth anniversary of Bob Spencer opening the curtain for Eddie's first solo performance at the theatre. Eddie's and Martha's pride and pleasure at being in Scottsville was evident, and the music was fine. It was a hometown night, full of smiles, laughter, jokes and love, all blended with soaring sound. Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum First Image Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, CD AEM01 AEM03cdAEM01.tif AEM03cdAEM01.jpg AEM03cdAEM01.psd Second Image Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, CD AEM01 AEM04cdAEM01.tif AEM04cdAEM01.jpg AEM04cdAEM01.psd Third Image Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, CD AEM01 AEM05cdAEM01.tif AEM05cdAEM01.jpg AEM05cdAEM01.psd Fourth Image Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, CD AEM01 AEM06cdAEM01.tif AEM06cdAEM01.jpg AEM06cdAEM01.psd Fifth Image Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, CD AEM01 AEM07cdAEM01.tif AEM07cdAEM01.jpg AEM07cdAEM01.psd Sixth Image Located On: Capturing Our Heritage, CD AEM01 AEM08cdAEM01.tif AEM08cdAEM01.jpg AEM08cdAEM01.psd All photos were provided by Eddie and Martha Adcock. References: |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum |

||||