|

|

|

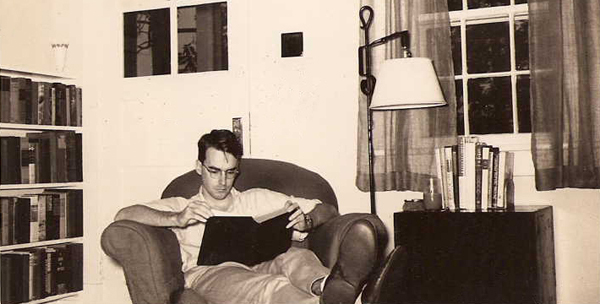

Name: Alan Martin Bruns Date: ca. early 1950's Image Number: AB48cdAB03 Comments: During World War II, Alan worked as a relief telegraph operator for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in Warminster, Warren, Hanover, and Williamsburg, Virginia. He temporarily left Scottsville High School (SHS) in October 1943 to fully learn the essentials of telegraphy. But Alan did return to high school after working for the railroad in 1943-1944, and also worked in the summers until 1947. He graduated from SHS in 1946, one year behind his original class. Alan's real love was the newspaper business, and after graduating from the University of Virginia, he became a writer for the Daily Progress in Charlottesville, and later, a city editor for the Richmond Times Dispatch, and a reporter for the Washington Star. Alan married first Jean Graham Randolph from 1952-1972, and secondly, Nancy Talmont. Alan passed away on October 21, 2009, at his home in Falls Run, Fredericksburg, Virginia. To learn more about Alan Brun's career as a wartime telegrapher, please read the following article about him by Ruth Klippstein: A Different View

By Ruth Klippstein Scottsville Monthly, 16 May - June 16, 2011

Alan Bruns of Howardsville, whose Scottsville High School memories were the feature article of Scottsville Monthly in September-October 2010, kept a second scrapbook of a special experience he had during World War II, when he worked as a relief telegraph operator for the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway in the Scottsville area. The story starts with his mother's letter to Principal Leslie Walton, dated October 28, 1943, when he was 16. "Alan will have to stop school and devote all his time to learning the essentials if he is to qualify for this job as telegraph operator. We have had long talks with Alan, who is indifferent to so many interests, but desperately in earnest about this. It seems that concentrating on this skill is what he wants most. He intends to finish his schooling later... He has been so interested in and so attached to Scottsville High that I hope he doesn't regret his decision after it is too late." Bruns did return to high school, but worked for the railroad in 1943 and 1944, as well as the summers until 1947, and graduated one year behind his original class. He later went to the University of Virginia and was a writer for the Daily Progress and copy editor for the Washington Star. Bruns' early interest developed when he "spent some nights at Warminister, where Charlie Morris was the midnight-to-dawn operator" and showed him how to use Morse code to telegraph. Bruns described the recruiting of relief operators in a history newsletter in 1994: "...many were needed to open evening and overnight shifts at rural stations to handle heavy wartime traffic. We teenagers and people past draft age or handicapped (a one-legged watchmaker, for example) helped make up for manpower losses through the draft. Older operators worked on instead of retiring. Telegraphers had worked a seven-day week even before the war, and that continued." Bruns was taught telegraphy by C&O agent, Tom I. Anderson, at Warren and proudly kept his first company identification card, insurance card, and examples of the train orders and other forms he had to fill out. He also saved his many penciled cartoons, as he did in high school, lampooning various railroad rules and regulations. ("Employees must not stand on the track in front of an approaching train for the purpose of boarding the same.") He includes the transcription of an actual telegram, noting wryly, "�we got some of the words." In a draft of an account Bruns later developed, he said that while telephones were beginning to supplant the telegraph, the older machines often were more reliable in bad weather and were used, theoretically, to keep the stations in contact with each other. "For the older operator, comic relief from the seven-day-a-week, sometimes 12-hours-a-day routine came when one of the semi-trained novices attempted to communicate with another by telegraphy. A simple message could take a half hour and be totally garbled when completed." Much of the work they did, instead, was taking Western Union telegrams, "various messages of less than vital importance." After his short stint at Warren Station, Bruns was moved to Hanover. At this time, the stops from Richmond west, after Hanover, included Sabot, Maidens, Rock Castle, and on to Columbia, Bremo, Strathmore, Shores, Nicholas, and Scottsville, to Warren, Howardsville, and Warminister, and finally to Gladstone, east of Lynchburg. In Hanover, Bruns lodged at the 1723 Hanover Tavern, and it's not clear how his historian's heart felt when he learned that the room below his was not actually that in which Patrick Henry supposedly shot a man, though that was how it was advertised. Bruns got advice from Anderson in a letter: "Don't get married over there. You will not want to come back." Bruns worked the 4-pm-to-midnight shift at Hanover. "Here," he wrote, "I made the first two major purchases of my life-a $50 second-hand watch and a three-year subscription to 'Billboard'-I still have the watch. A night job provides a lot of spare time, and I was soon spending the time in drawing--including designs for model offices with suspiciously comfortable-looking seats and silencers for the telegraph instruments." He roomed with the section foreman until he moved on, and Bruns wrote to his mother, "I live in my shock alone now�I may get home after this job, but there's no way to tell how long I'll be here." May 21, 1944, Bruns was given a new assignment, the "second trick" at CB Cabin, 3 to 11pm, near Williamsburg and the trunk line to Camp Peary, where the Seabees trained; he joined the Order of Railroad Telegraphers. His archived W-2's indicate that he made $108 in 1943, $1790 in 1944, and lesser amounts after he returned to high school during the next three years. He sent money home to his mother to do his laundry, but bought his own supplies and clothes. "My favorite wartime railroad memory," he wrote in 1994, "is how we handled a blackout test--we took the kerosene lamp off the desk that was built into our depot bay window and put it on the floor underneath the desk. The glow in the sky above Richmond, visible about 20 miles away, dimmed--but, it seemed only slightly. Wartime shortages made certain things, such as white shirts, almost impossible to find. When some shirts, made from heavy material, went on sale in Richmond, a friend and I stood in line. Boarding houses, if available, asked for our ration books. Sometimes, there was nearly no place to stay. At CB Cabin, I lived in a combination of what had been a small trailer and a shed." He applied to Mr. Anderson for help finding lodging; Anderson noted that there were "plenty of jobs in places that don't have electric lights," and mentioned the "heavy movement of troop trains," but he thought well of Alan's progress with both telegraphing and the railroad's book of rules, and suggested that Bruns might want to stay on there, as it was "near many things of interest to see in Williamsburg and Yorktown." This is where, Bruns later recalls, he was taught to shoot craps. The trains rolled on: Old Point Junction, Morrison, Lee Hall, Norge, and Providence Forge. "Everybody loves the sound of a train in the distance," songwriter Paul Simon says. There must have been romance for Bruns, but some hair-raising episodes as well. He recounted the "sinking feeling one gets when a 160-car coal train has to stop (it takes a mile or more for it to stop) "because the string holding the train's order delivery was not set in its string loop correctly by the dispatcher so that the trainman could stick his arm out and retrieve it; and the "real jeopardy the traveling public was subjected to when teenagers were assigned to an 'interlocking plant.'" This set of levers and handles controlled various signals or switches that guide train traffic within limited areas--a rail intersection, a rail yard, or even some miles of track. "They were arranged to eliminate human error," Bruns wrote, but "no machine can completely achieve this." He described a lone engine mistakenly sent down a track leading along the James River toward Lynchburg. "Heading in the opposite direction on this track--still some distance away but virtually unstoppable at this stage--was one of those 160-car coal trains. All this," he wrote, "unfolds on the C&O's viaduct over Richmond's riverfront. On this day in the mid-1940's, the whole neighborhood almost got demolished the hard way--by flying coal cars." "No written record exists of the remarks of the man on that lone engine who sweated out the several minutes it takes a timelock to run out so he could get back through the switch, have it thrown again so he could get to the station, and for it to be thrown again for the eastbound coal train so it wouldn't descend from the viaduct with a crash. It can be stated here, however, that the teenage railroaders learned a lot about the world in their work. "At least one," he continued, "never since has heard anything to equal the vituperation that ensued when the man who had been on that engine presented himself face-to-face with the teenager in the interlocking tower... Had it not been that the tower stood fairly high above the rest of the station area at that point, it might have been that the engineer wouldn't even have found the teenaged leverman there, but it was a long way to the ground, and the engine man came up the only steps. All in all, some count themselves fortunate even to have survived this era of railroading. Some of the former novices, for example. And many, many, many professional railroad men greeted the end of World War II with an added touch of joy. Not only had peace returned, but so had sane, mature telegraph operators and interlocking tower men." When classes took up in September, 1944, Alan Bruns was again walking between the rows of boxwood up to the Scottsville High School doors, trading jabs with his friends, taking tests, and planning for the future. But his scrapbook contains photographs of him in later years, revisiting the Hanover Tavern and old depots at Warren and Howardsville, with other railroad aficionados. The sound of a train in the distance must always have been a very special music to his ears. [The Alan Bruns notebooks are currently being archived for the Cenie Moon Local History Corner of the Scottsville Library, and will be available to the public soon.---rk] Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

||||