|

|

|

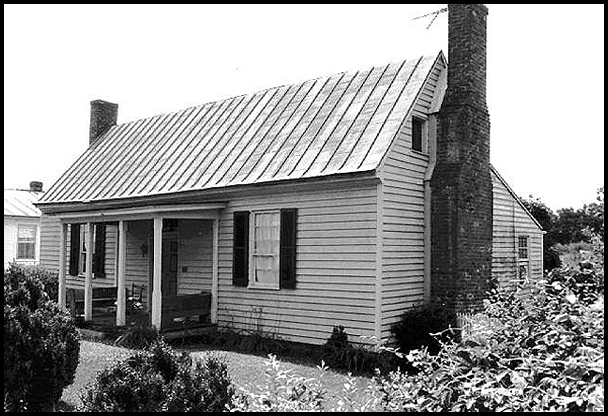

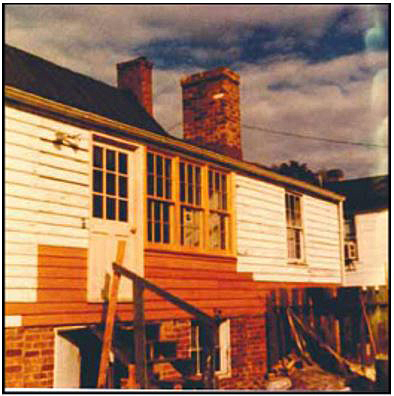

Name: The Herndon House Date: ca. 1975 Image Number: KEL01cdKEL01 Comments: The Herndon House was built between 1800-1810 and is located at 347 East Main Street in Scottsville. Similar in design to the Colonial House next door, the Herndon House is a frame dwelling with weatherboard siding. It is a 'double house' with a chimney on either end and a front-to-back central passageway. The Herndon House is one of 53 historic buildings in Scottsville's 1976 historic district listing on the National Registry of Historic Places. Shown below is a 2010 photo of the Herndon House in Scottsville:  To learn more about the history of the Herndon House, please read the following article by Ruth Klippstein that appeared in a 2016 edition of the Scottsville Monthly: How The Herndon House Endured by Ruth Klippstein The small house at 347 East Main Street, now painted gray and prettily set off by a white picket fence and two cherry trees in the front yard, has recently changed hands. The Herndon House has been a fixture of the Scottsville real estate market lately, but its construction -- estimated between 1790 and 1840 in printed sources -- dates back to the earliest days of the town. Debi Dotson, who sold the house for owners Christopher and Deborah Shook in 2004, and again this past December, says this building "went from hand-to-hand in nineteenth century Scottsville," having been owned in its early life by Jonathan Pitts, whose imposing c. 1831 brick house (regrettably razed in 1955) was further west, now the site of East Main garage. The first Herndon mentioned in relation to the structure in Albemarle County records -- which go no further back -- is Robert, who was living in the house on February 28, 1883, when Luther and Lillie Pitts, and Richard, Mary, and James Tutwiler conveyed it to him. By 1926, when the house and its two lots were owned by Laura Herndon and her current husband, Charles Stieren, Robert Herndon had been dead "for several years." John S. Martin, Senator Thomas Staples Martin's brother and owner of other Scottsville property (including Cliffview, now the home of George and Lucinda Wheeler), bought the house; the deed was notarized by S.R. Gault. Martin sold it in 1931 for $3000 to Sallie Marsh; and Mrs. Marsh willed it to her nephew, Harold Parr, and his wife, Ruby. With the introduction of these names, some people in Scottsville begin to remember who lived in the Herndon House, or at least to recognize the place. It hasn't loomed large in Scottsville history. Pat Pitts and Bill Mason, reliable keepers of our local stories, concur that there must have been no children there, or they'd certainly remember more; 96-year old Margaret Duncan agrees. Bill Mason's parents lived across the street, and he says Sallie Marsh and other women on the end of Main were friends of his mother. Hunter Woody, who with his wife, Eula, still lives across the street, does not recall any particular stories of the house or of its inhabitants. Marshall Johnson remembers nothing to add. The Parrs, whether they lived at Herndon House or not -- before moving to Chester on James River Road -- sold it in 1976 to the Duffs. The price was up to $27,000 then, its flood plain location still vulnerable to the two big hurricanes and more to come. In 1977, the Duffs sold the house to Halsey Scott, who in 1980 sold it to Karen and Andy Johnson. The Johnsons would renovate it and hold on to what Andy calls "a really neat little house," working and raising their daughter, until 1991. (The house changed hands in 1993, 1998, 2004, and December, 2015.) Andy Johnson was then restoration specialist and later architecture conservator at Monticello. Expanding into his work there, he undertook a major, time-consuming renovation of the Herndon house. The back porch became a new kitchen, with the addition stretching across the entire rear facade; they exposed the original cornice on the roof -- "Which is really fancy," Andy notes; and uncovered the ornate dentil woodwork on an interior wall. Bob Self, who later became architecture conservator at Monticello and at this time, owned a furniture restoration shop in Scottsville, helped to extend this woodwork the full length of the current room. Mac Derry and Peter Marks worked on the carpentry, Richard Scharer on the masonry, and Joe Madison was part of the crew. Earlier work which Derry executed in Scottsville included repointing the brick of Haden Anderson's Jackson Street home. This group of men were friends, all young and skillful, as well as lively. One day, returning from his job, Andy found "one god-awful pink brick" placed by Scharer in the repaired chimney. It would later be covered by the flashing, and was there just to tease him, a construction joke. Mac Derry remembers that when the new kitchen was beautifully completed, Andy looked around and said he would "fly speck the ceiling with sepia paint." Karen, his wife, "gave him this look like, 'idiot!'" Andy claims no recall of this sequence of events. There are two exterior chimneys on the ends of the Herndon house -- standing several inches away from the structure, as they were usually made in the early nineteenth century --- and a metal steeply-pitched gable roof. Andy found an "incredible fireplace" in one of the two front rooms, highly decorated with a surround in a sunburst pattern made of little pieces of wood; it did not match the fireplace of the other room. The interior doors of the house had all been cut in half when the Johnsons moved in. Andy put in new ones and grained them in the "fancy painting" style he was beginning to use at Monticello. When writing about the house in 2002, Rosalind Warfield-Brown noted in "The Hook" that "the place's plain charm" is enhanced by Andy's "beautiful work and artistry," including an "interesting painted pattern on the dining area floor." Historic information on the Herndon House is scant. Ed Lay, former dean of UVA's School of Architecture, writes about it in "Architecture of Jefferson's Country": "The ubiquitous single-cell, one-story frame house persisted well into the nineteenth century. The Herndon house, a one-story dwelling in Scottsville, began as a single-cell frame house. Its features include double-ramped brick chimneys, beaded siding, and nine-over-six sash windows." The 1976 registration form for Scottsville's Historic District, which includes this structure, says "the earliest buildings in the district contain very few stylistic elements; the character of these buildings is based mostly on their form." The Department of Historic Resources in Richmond details a partial-width front porch which is "supported by posts, and a four-light transom," distinguishing it from its neighbor to the west, the Fore House, or Colonial Cottage.  Looking south out of the Herndon kitchen addition's window The first Herndons came early to America from England, and some of the brothers migrated south to Virginia. The Scottsville Museum owns a Scottsville business ledger from 1889-1893 that lists five different men with this last name trading locally; Albert and Benjamin Herndon are buried in the Scottsville Cemetery; Anna Herndon is pictured in an 1892 Scottsville School photograph. I asked some of the area's Herndons if they knew of a connection to the old Herndon house. Leroy Herndon said, "Not all Herndons here are kin to the original Herndon -- there were others." Leroy's sisters, Lillian Hamshar and Etta Collins, are equally equivocal. Lillian says, "Chances are great that the house was owned by one of our ancestors. There are many around who were, and we think we're all connected, but it's so far back that we don't have proof." Some printed sources suggest the house is small enough to have been designed originally as an office for the canal company. It was well- sited for that, close to the canal, the warehouse, gauge dock, and turning basin. Warfield-Brown opines in "The Hook" that "it does seem a shame that modern adaptation, possibly including carving up the space (into offices) may be on tap for an appealing old place that has endured so much." I can find nothing to corroborate the idea that the building was an office for the canal company. Whether it was constructed in 1790 or 1820, the canal then was just an idea in its infancy, and the James River Company, chartered in 1785, was trying to make the river itself navigable, especially around Richmond. This was expensive and basically a failure; the state took control in 1820 and resumed work. In 1835, the James River and Kanawha Canal Company was instituted to forward the effort. That decade saw much activity, with work being pushed towards Scottsville but lots of disagreements with landowners along the route -- similar to the natural gas pipeline controversy today -- and trouble with salaries and hierarchy. In 1836, the lock keeper's House at Lock 7 in Goochland (much more substantial than the Herndon House and still inhabited as a private home) was built, indicating big hopes and lots of effort. During the last months of the Civil War, when Union forces under Philip Sheridan entered Scottsville, the useful infrastructure of the Confederacy was their prime target. Chief Engineer of the James River and Kanawha Canal Company, Edward Lorraine, reported detailed destruction of bridges, dams, locks, and in town, the "Company's shop burnt with all tools, forage...timber...as well as 200 pounds of beef and a barrel of flour." Richard Nicholas studied tax assessments before and after the war to evaluate collateral damage -- homes burned by being too near actual targets, and discovered that Lots 22 and 10, site of the Herndon House, were three lots east of any burning. "Four Decades of Social Change, Scottsville, Virginia, 1820-1860," a UVA dissertation by Karl Hess in 1973, notes that "in 1820, there were only two merchant's stores, a warehouse, a ferry...and several modest homes" in Scottsville. Development occurred in the next generation, as families consolidated and population grew; the Staunton and James River Turnpike opened; and the canal began collecting tolls. It seems easy to imagine that one of these modest homes was the Herndon House. Jack Larkin, in "Where We Live, the American Home from 1775 to 1840," says that "the South had a higher proportion of very small houses than New England." And this house was certainly large enough for many a family. The charm of this little structure (Debi Dotson, real estate agent, notes the "utterly amazing floors," original newel posts, and windows.) was not easily won. Six months after Andy Johnson finished his restoration and took a family vacation, the November 1985 hurricane roared in. Friend and housekeeper Gloria Scharer unlocked the house and moved what she could to the top floor. I was there that November 12, Wellington-booted and bandana'd, helping shove water and muck out the front door with mops. Andy recalls that when they arrived home, the family found, in the middle of their wet, mud-coated new house, a cabbage sitting ten steps up the interior stairway. Herndon House continues to look better and better and to help tie together visual improvements from East Main to north on Valley Street. As it evolves, we can echo "The Hook:" "Any use that keeps the house vital and alive will be fine with us."  The Herndon House's kitchen addition seen in construction in 1980's. Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum |

||||