|

|

|

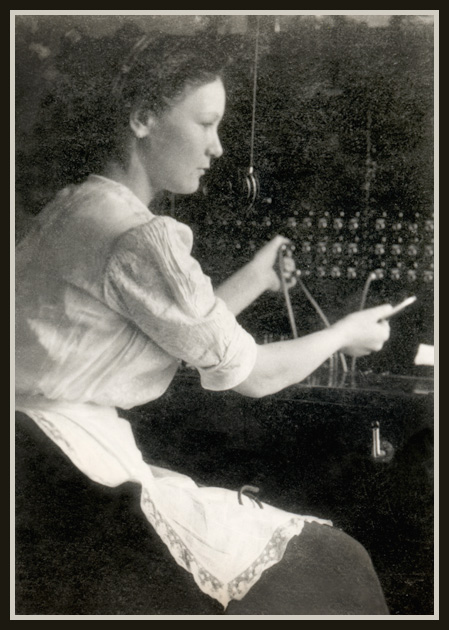

Name: Edith Taggart, Scottsville Central Date: ca. 1915 Image Number: B264cdB25 Comments: Edith Taggart served as Scottsville's central telephone operator from 1911 until her retirement in 1950. She was our 'Central.' Every Scottsville telephone call outside a subscriber's party line was placed through her. A caller turned the crank of a magneto telephone and generated a ringing current at Edith's switchboard. Edith would tap into the calling line and ask, "Number, please?" "Ring up Jim Tindall for me." Edith knew the phone numbers of everyone and connected this caller by plugging a cable between those two phone jacks on her switchboard. Next she rang up Jim Tindall's phone with one long ring and four shorts: R-I-N-G, ring-ring-ring-ring. Once someone at the Tindall home picked up the phone receiver and said, 'hello,' Edith's work was done � for that call.

Despite being crippled by polio as a child, Edith excelled in her role as our Central. She stayed on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week for thirty-nine years. Her hands flew across the switchboard, making connections. Edith always knew what was happening in Scottsville, and often townspeople would call her to get 'the news' or leave messages. "If you see my husband, tell him to call home - his dogs are fighting again." Edith peered out the window from her Central Office vantage point on Valley Street and spied the husband walking into a store. Turning back to her switchboard, Edith told the caller, "Oh, he just went into Omohundro's Hardware. I'll connect you over there." During World War II, Edith only needed to know a soldier's name and the state in which he was posted to connect a call to him. Her employer, Virginia Telephone and Telegraph, rated Edith as their company's best operator. Scottsville certainly applauded Edith for that well-deserved plaudit, but they knew their Central meant even more to their community. Edith's personal relationship with Scottsville was unique -- she carried the whole town in her mind and in her heart. She was beloved in Scottsville. Some folks called Edith when they were lonely, just to hear her familiar voice. "Hello, Central." When Edith responded, the caller believed that 'home' was still in good hands. One resident, Nell Bolling, named her daughter, Edre, after Edith - not unlike the central character in Mark Twain's A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court, who was inspired similarly by his telephone operator and named his daughter, 'Hello-Central.' Children and adults enjoyed Miss Edith's company and sought her out. She knew interesting people and, of course, 'the talk of the town.' But even greater attractions were Edith's quick wit, good humor, love of people, and demonstrated ability to excel despite her physical infirmities. How did Edith get her start? She was born on September 17, 1898, to Martin and Nella (Payne) Taggart of Buckingham County. Her father worked as a salesman in the county's Slate River District and died before 1910, leaving Nella to raise their three children, Melvin, Edith, and Gladys. To make ends meet, the family moved in with Nella's mother, Mary E. Payne. Then a polio epidemic struck their Buckingham community, leaving five children afflicted with polio, including Edith and her cousin, Bolling Skidmore. When she was eight years old and in the third grade, Edith was stricken with polio. Her mother called Scottsville's Dr. Bowles to their home to check on Edith's medical condition. Completing his examination, Dr. Bowles pulled the sheet back up to Edith's neck and turned to her mother with his diagnosis: "This one is a goner!" Even years later, Edith remembered the terror she felt upon hearing those words. She credited her uncle, Samuel 'Sammy' Payne, for pulling her through that night. First Uncle Sammy comforted her and then concocted a big batch of mentholated salve to help her breathe. He put the pan of salve under her bed sheet and asked her to pull the sheet over her head and breathe deeply to help clear her breathing passages. Edith trembled helplessly with fear, and so Uncle Sammy hopped under the sheet with her. All night long he held that sheet up to form a tent filled with mentholated vapors that helped Edith breathe. In the morning, her breathing was better, and Edith would survive her bout of polio. But polio left Edith unable to walk without heavy braces on her legs and crutches.

In this 1908 photo of the corner of West Main and Valley Streets, the Dorrier building is the two-storied

building at photo left.

In 1911, the Taggarts' second floor apartment in the Dorrier building overlooked Valley Street. To make ends meet, Nella Taggart began working as Scottsville's telephone operator. She moved her family into an apartment above Dorrier's Store (280 Valley Street). This building stood at the southwest corner of West Main and Valley Streets, and Nella's switchboard sat at a second story window with a full view of Valley Street. Edith played nearby and watched her mother work. Homebound and unable to attend school, Edith perhaps viewed her mother's switchboard as a welcome connection to a more interesting world than four apartment walls afforded. Edith quickly learned telephone operator's skills and began working the switchboard full time in 1911. She was 13 years old, and next to her switchboard was the cot on which she slept. About 2AM, Edith would take off her braces and go to bed. If the switchboard buzzed in the middle of the night, it might take Edith a minute or two to get there from her cot. But she'd answer the call and make the desired connection. The role of Central for Edith was a 24-hour a day business. In the early 1900's, telephones were really in a primitive state. There were all kinds of crackling and clicking noises on each party line, which was shared by six to eight families. For two people to actually conduct a conversation, a friendly operator was needed to make the experience less worrisome and annoying to the subscriber. Edith developed a jolly, jovial line of patter that endeared her to local phone users. Several longtime Scottsville citizens remember how good it felt when they were traveling just to call our Central and hear a familiar voice from home. Edith knew her local phone subscribers and did her best to handle every situation calmly and effectively. During her freshman year at college, Virginia Tindall remembered calling her mother in the middle of a terrible thunderstorm. "We were cut off, and I called back and told Miss Edith, 'I want to speak to my mother.'" Invoking her most reassuring tone of voice, Edith told Virginia, "Your mother is perfectly fine." Edith knew it was late and that the Tindalls had one phone downstairs and none in Mrs. Tindall's bedroom. So she continued her logical assessment of the situation with "And I'm not going to call your mother back because she's gone to bed." But Virginia insisted, "Well, I WANT to talk to my mother to see if she's alright." Edith finally called Mrs. Tindall and let Virginia talk to her mother. When they hung up, Virginia said she realized she'd made her mother walk all the way downstairs in the dark to answer the phone. "And Edith was trying to tell me that." Some locals called Edith and engaged in humorous exchanges. Virginia Lumpkin

recalls one such story about a man who got drunk in Buckingham and called Scottsville's

Central. Edith had taken off her braces and gone to bed when the switchboard rang.

Although she had just dozed off, she answered the call. It was Luther Baber, who said,

"Miss Edith ... get me ..." He mumbled the name of the person he wanted to call, and

so Edith asked, "Who are you calling?" "I want to call Heaven!" Figuring that she

was still half asleep and not hearing him correctly, Edith restated the question, "Who do you

want to call?" "I want to call Heaven!" "And who do you want to speak to?" she

queried. The drunk said, "Jesus." Edith replied firmly, "Luther Baber, if you

don't get off that phone, I'm going to give you Hell!" And she hung up on him. The

caller reportedly got so mad that he threw his phone out in the middle of the road, an act he

surely regretted the next morning.

By the mid-1930's, Dr. Luther Stinson built a small brick house up the street at 460 Valley Street to serve as the central telephone office and home for Edith and her mother. Its one floor design better accommodated Edith's infirmities. The Kirk Spencer family lived nearby with their young son, Bobby, and were good friends of the Taggarts. Today, Bobby recalls spending many hours playing by Edith's switchboard as his mother visited in the Taggart home. He says that Sunday evenings at the Taggarts were particularly enjoyable. As Miss Edith worked the switchboard, her mother would sit in the adjoining room, listening to radio programs on her big console radio or playing their piano. Edith always dressed for work. Each morning she got up and painstakingly fixed her hair and donned a long tailored dress to hide her heavy leg braces. Over the years, she received many presents of costume jewelry from her friends in the community. Invariably, Edith would don earrings and sometimes a pin or necklace to ensure she was properly dressed for the job. When she began each work day as Central, Edith was dressed for success. Edith enjoyed taking the afternoon off when a temporary operator would spell her for several hours. Some of the operators, who helped with Edith's switchboard duties, were Frances Faulconer, Frances Maupin, Joyce Mason, and Annie Pearl Moore. Edith first would rest for about an hour and then go down to Bruce's Drugstore in her wheel chair for a cherry coke. She would sit at a soda fountain table, smoke cigarettes, and talk with others in the store. Edith always used a long cigarette holder, which some felt made an elegant statement in those days when smoking was more commonplace. As teenagers, Bob Spencer and his good friend, Pete Deane, often visited with Edith because she was so jolly and told great stories. Pete nicknamed Edith 'the Dragon' because she blew smoke much like he imagined a dragon might. When these two young men needed a break from their studies, Pete would say to Bob, "Let's go down and talk to The Dragon!" And off they would head to find Edith. By 1950, the Scottsville party line phone system had grown immensely and was headed to a dial phone system by 1952. Many in the community rued the passing of a system in which Edith's personal touch enabled callers to leave messages and divert calls. However, the days of Central everywhere were numbered. In Scottsville, the new dialup equipment required a new plant, one that could no longer house our Central. Edith would soon be both jobless and homeless.

In retirement, Edith was ineligible for social security benefits and had meager savings, no home, and no family in the area. Her mother, Nella, was deceased, and her brother, Melvin, lived far away in Baltimore. So Edith moved to the Traveler's Rest Hotel where her good friend, Virginia Lumpkin, gave her free rent and meals for the next 18 years. Edith sewed her own clothes and babysat Virginia's children, Hollis and Marlean Lumpkin (shown at right). She also earned some money for personal expenses by altering clothes for the Scottsville community. But Mrs. Cohen, Dr. Stinson, Dr. Moody, and others in the community voluntarily supported Edith with small financial contributions. Edward Dorrier would visit Miss Edith monthly and, without a word, slip a few dollars under her dresser scarf as he rose to leave. Scottsville took care of its Central, a woman who unselfishly had worked and cared for the town since 1911.

Beginning in the 1940's, arthritis became a health issue for Edith. She found a chiropractor on Franklin St. in Richmond, whose treatments provided her some much welcomed relief from arthritis pain. The chiropractor was located near the posh Jefferson Hotel, and Raymon Thacker of Scottsville, an old friend of its owner, arranged for Edith to stay at the Jefferson during her treatments for only $1.50 a day. After Edith retired, she would save up her money and go to Richmond for treatment when she could afford it. Often the Lumpkins would drive Edith there and pick her up at the end of her stay at the Jefferson. Edith also helped the hotel run its phone switchboard and took on sewing tasks, too. According to Bob Spencer, Edith met some very interesting people while working the Jefferson switchboard, including Clyde Beatty, the lion and tiger tamer; Mantovani, the famed British conductor; and others.

Today, thirty-five years after her death, Scottsville still talks fondly about the impact Edith had on our town. A musical history of Scottsville, written recently by Langden Mason and performed at Victory Theater, included a piece on Edith Taggart. Anne Condon of Scottsville starred as the musical's character, Edith, and sang a song entitled Talk of the Town: "...it's not really gossip, it's talk of the town...." Indeed, our Edith Taggart was a 'character' and a much cherished member of our community. Memories of Edith Taggart

A. Scott Ward, October 09, 2004: "My very first phone call was through the Scottsville Switch Board.

My mom, Ellen Ward, was sick, and she said, "Alex, please go get Aunt Elizabeth Napier." So I walked across the old

James River Bridge, and as I was passing Pitt's Chevrolet Garage, I thought, "Why not call her?" So I went into Pitt's Garage

(actually the show room) and asked to use their phone. They handed it over the counter, and I cranked away. Miss

Edith came on the line, and I told her that I wanted to speak to my Aunt Elizabeth Napier. She said, "Hold on, Son!", and the

phone rang. I saved myself a mile of walking. I was only 6 years old at the time!" ---------------

Robert K. Spencer, September 18, 1985: "Edith Bolling Taggart, better known as "Miss Edith," would be eighty-seven years of age on September 17, 1985, if she were still with us in person, but to most who knew here, she is timeless and a part of the spirit of Scottsville whose voice may still be heard echoing on the telephone lines around the town. In her thirty-three years of faithful, efficient service, day and night, as chief switchboard operator "Central," before dial phones came into use in the area, she rightfully gained the title of "The Voice of Scottsville." Her strong, clear, well-modulated voice compared favorably with any big city operator's of that era, and she could get you through to anywhere in the world that there was a telephone. It is said that at one time an inebriated caller asked her to give him Heaven, whereupon she promptly offered to give him another equally well known place if he didn't get off that line at once!" "Miss Edith learned to be "Central" from her mother, Nella B. Taggart, who held the position before her. Stricken with polio at the age of eight, Miss Edith was confined to a wheelchair most of the time but nearly every day walked some with the aid of crutches. In fact, one of her favorite daily activities was an afternoon stroll down to Bruce's Drug Store on the Corner, where she would enjoy a large Cherry Coke and sometimes a dish of ice cream. (Until the early '50's, Bruce's had a soda fountain with seats.) Miss Edith trained assistants to relieve her for several hours in the afternoon." "At the switch board, besides performing her regular duties of putting through all calls, Miss Edith was like a receptionist for every professional and businessman in town and the entire area. If a doctor was making a house call, she knew exactly where he was and when he would return to his office. A lawyer or a politician, in Charlottesville or Richmond for the day, could be reached by her if need be. She knew where electricians, plumbers, carpenters, and farmers were working on any given day. So well did she know the lifestyles of everyone served by her switchboard that she knew how to contact almost anybody at anytime. She did not hesitate to interrupt lengthy conversations on party lines for emergencies. There were few, if any, "crank" calls other than turning the crank in those days because Miss Edith knew who was responsible for any number plugged in, and she was known to have an adequate vocabulary to quell any abuse of the telephone. In short, she gave the ultimate personal touch to telephone communication of an earlier time." "In May 1950, Miss Edith retired from her post, probably realizing that soon the dial system would replace her. (The dial system was inaugurated here in July 1952.) She then moved to the old and well known Traveler's Rest Hotel, which was then operated by Virginia McGrow (now Mrs. Nelson Lumpkin, proprietor of Lumpkin's Restaurant). (The old hotel was destroyed by fire several years ago.) In retirement, Miss Edith resided part of the time in the famous Hotel Jefferson in Richmond, where she sometimes worked the switchboard. She loved to meet people, and there she got to meet and take messages for many personalities, including Marge and Gower Champion, Betty Hutton, Mantavanni, Gene Autry, and Clude Beaty." "Virginia Lumpkin did so much to make Miss Edith's retirement years pleasant ones, and she saw that she was cared for during her final illness. They say Miss Edith died on June 21, 1968, but some of us like to think "The Voice of Scottsville" may still be on the line." The above photos are part of the Raymon Thacker, Robert Spencer, and Virginia Lumpkin collections at Scottsville Museum. All three donors resided in Scottsville and were dear friends of Edith Taggart. Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2018 by Scottsville Museum |

||||