|

|

|

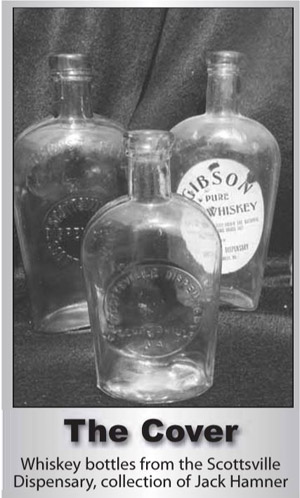

Name: "Bottles Tell Scottsville's History"  Little's White Oil Bottle loaned by Jack Hamner of Palmyra, VA "The earliest known embossed Scottsville bottles," Jack continues, "were designed to contain horse liniment, although this Little's White Oil was purported to benefit man as well as beast. This patent formula, invented by C. E. Little of New York State, was produced as early as 1837 and "although the elixir itself would remain virtually unchanged, the bottles underwent many transformations, from free-blown to machine-made with cork closures to screw top," Jack says. The Little brothers, C. E. and T. W., on a selling trip through the South, were impressed by Scottsville's potential as a transportation hub and moved here in 1842; they became involved in many businesses, running a grocery, a wool-carding factory, and a broom factory. "Bottles of Little's White Oil and their contents probably had the longest life span of any Scottsville product," Jack says, being sold throughout 23 states, "making an impressive run from the mid-1800's to possibly the 1940's or '50's. All bottle variations were either aqua or clear flint glass and were embossed 'Little's White Oil Scottsville, Virginia." An old pamphlet that Jack owns extols the virtues of this mysterious concoction for ring worm, sprains, and rheumatism, as well as any horse ailment. According to this advertisement, the oil was "prepared and sold by W. D. Hart, of this place." The testimonial of John S. Martin in 1848 (brother of U.S. Senator Thomas Staples Martin and, at that time, owner of Cliffside) says that after a 200-mile trip on his "very much galled horse," the liniment healed the animal quickly. People from other states wrote about its "almost miraculous" qualities--possibly a reason for its remarkable longevity, Jack thinks. "Had not the automobile overtaken the horse as the vehicle of choice, we might perhaps still be rubbing Little's White Oil on our horses as well as ourselves."  The next container to appear, Jack says was a clear or sun-colored amethyst strap-sided whiskey bottle embossed "Scottsville Dispensary, Scottsville, VA."

This bottle came in half-pints, pints, and (rarely) quarts. There are at least two lettering variations as well as one plain example with a paper

label which reads "Gibson Pure Rye Whiskey" -- (and another called "Old Jasper," as seen in the Scottsville Museum) by "Scottsville Dispensary, Scottsville,

VA." Although absolute dates of production of this whiskey are not known, Jack's educated guess would be from the late 1800's up until the time of

Prohibition. The original dispensary building was a large brick structure on the site of the present day Scottsville Police Department building, the

former Silver Grill. The brick structure was bought by Dr. Percy Harris, and the bricks re-used to construct his residence, still sitting on a rise

above a rock wall between Dorrier Park and the Scottsville School Apartments.

The next container to appear, Jack says was a clear or sun-colored amethyst strap-sided whiskey bottle embossed "Scottsville Dispensary, Scottsville, VA."

This bottle came in half-pints, pints, and (rarely) quarts. There are at least two lettering variations as well as one plain example with a paper

label which reads "Gibson Pure Rye Whiskey" -- (and another called "Old Jasper," as seen in the Scottsville Museum) by "Scottsville Dispensary, Scottsville,

VA." Although absolute dates of production of this whiskey are not known, Jack's educated guess would be from the late 1800's up until the time of

Prohibition. The original dispensary building was a large brick structure on the site of the present day Scottsville Police Department building, the

former Silver Grill. The brick structure was bought by Dr. Percy Harris, and the bricks re-used to construct his residence, still sitting on a rise

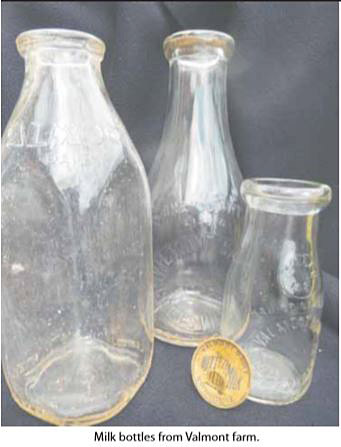

above a rock wall between Dorrier Park and the Scottsville School Apartments.With the arrival of the twentieth century in Scottsville came the advent of no fewer than four new bottled products, Jack says--milk from two dairies, spring water, and a cola drink. "Although exact dates are once again hard to establish, all four of these new companies probably came into being more or less simultaneously around the second decade of this new century."  Valmont Dairy was a large farm just north west of Scottsville; its rolling green hills overtook the James River. It boasted a large herd

of golden Guernsey cows, whose milk was bottled on site and delivered throughout the community by a fleet of trucks driven by local men.

Valmont was by far the most widely promoted dairy of the Scottsville area, and Jack has collected many advertisements, calendars, giveaways, and

photographs which can still be found at sales on occasion. The dairy changed hands many times; it was owned by William Moon, Peyton Harrison,

the Gantt family, and finally, Dr. R. L. Stinson. Valmont Dairy was a large farm just north west of Scottsville; its rolling green hills overtook the James River. It boasted a large herd

of golden Guernsey cows, whose milk was bottled on site and delivered throughout the community by a fleet of trucks driven by local men.

Valmont was by far the most widely promoted dairy of the Scottsville area, and Jack has collected many advertisements, calendars, giveaways, and

photographs which can still be found at sales on occasion. The dairy changed hands many times; it was owned by William Moon, Peyton Harrison,

the Gantt family, and finally, Dr. R. L. Stinson.Valmont bottles came in half-pints, pints, and quarts and a few lettering variations, although these, Jack says, were limited in nature. One interesting side note is that Scottsville was incorrectly spelled "Scottsville" on a precious few half-pint bottles. Evidently this mistake was soon corrected, as Jack has only one example of this error.  The other,

but much less known dairy with the embossed Scottsville name, Jack says, was Snowden dairy, just across the James River in Buckingham County.

Bottles have been found in pints and quarts, but are quite scarce. "Just as scarce is concrete data concerning this quaint dairy.

Worth noting while discussing local dairies is the herd at Fair View Farm on the east side of Route 20 north of town. It was operated by

Jack Manahan's father. Milk produced there was sold in bulk to Monticello Dairy of Charlottesville, who marketed it under their franchise. The other,

but much less known dairy with the embossed Scottsville name, Jack says, was Snowden dairy, just across the James River in Buckingham County.

Bottles have been found in pints and quarts, but are quite scarce. "Just as scarce is concrete data concerning this quaint dairy.

Worth noting while discussing local dairies is the herd at Fair View Farm on the east side of Route 20 north of town. It was operated by

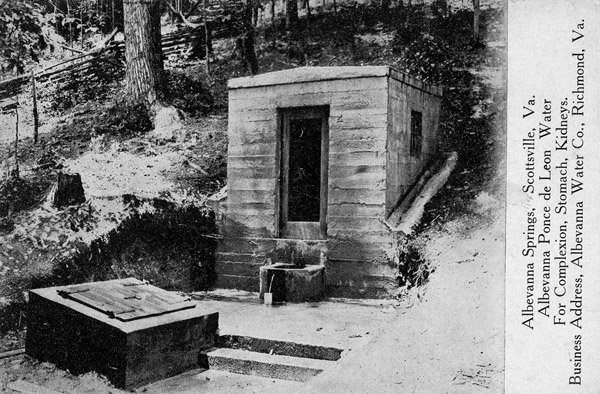

Jack Manahan's father. Milk produced there was sold in bulk to Monticello Dairy of Charlottesville, who marketed it under their franchise.Another example in the twentieth century lineup of Scottsville bottles is a soft drink, "Christo Cola--The Nation's Joy Drink." "Scottsville, VA." is embossed on the bottom of the bottle. Jack says, "I have never tasted it, but my best guess would be that it is much like Coke or Pepsi." Christo Cola was bottled by Dr. Harris, who lived in the West Main Street home constructed of Scottsville Dispensary brick. Before Dr. Harris bottled the drink in recycled bottles, the glass had to be thoroughly cleaned. "That task was awarded to my father," Jack says, "who was a young but enterprising boy in about 1911. Dr. Harris would prepare a large vat, fill it with water and heaven knows what else, and sink the used bottle down into it. My father's job, paid at something like a penny a bottle, was to remove all old chewing gum, flies, ants, straws, cigarette butts, bees, small mice, and whatever else may have found its way into those bottles. He then washed them with soap and water, rinsed, and maybe even sterilized them (but I doubt it!). They were then ready to be refilled, although where this happened, I don't know. Neither do I know any more about this business. I own a single Scottsville Christo Cola bottle." Jack tells us that "just southeast of Scottsville, on Albevanna Spring Road, there stands a wonderful spring which produced an extraordinary water that not only tasted great but many believed possessed amazing curative powers. The water, called Ponce de Leon, was bottled and sold in large aqua glass bottles, in wooden crates, as well as paper-labelled quarts, but no embossed examples are known to exist. Savvy marketing strategies were employed by this company as evidenced by extensive pamphlets, fliers, and even William Burgess stereo postcards," one of which shows the elite young of Scottsville in turn-of-the-century clothing, enjoying a summer outing to the spring. One advertisement lists the water's benefits for complexion, stomach, and kidneys. Testimonials include B. L. Dillard's, a Scottsville doctor, who said he recommends it to patients for bladder and kidney troubles, one "can see no reason," he writes, "why the Albevanna Spring should not become very popular as a health resort." In 1934, Dr. Percy Harris of Scottsville also gave an endorsement for the water, which contains measurable calcium, iron, magnesium, potassium, silica, and other elements. Keith Van Allen has coordinated much of the Anderson family history, gathering memories from the extensive and ebullient clan. Their quick wit and playfulness are evident in the stories, as well as strong ties to each other. Mollie Anderson, at 100, Keith says, "is always talking about the spring, and we all do. It's so central to the soul of the family." "Mollie remembers the pond and picnic table by it, Papa Anderson (her father, D. Wiley Anderson, 1864-1940) fishing for frogs which Mama would cook for him." The family had lively reunions over the years at the Albevanna Springs house, Keith says, where D. Wiley Anderson had developed the spring, built a bottling house by the road, and was selling Albevanna spring water in Charlottesville and Richmond as early as 1911. Thomas Staples Martin once took some, a Congressional Record notes, to distribute at the Senate. American springs' rise to fame followed the practice of the well-to-do in Europe "taking the waters." A family in Maine started bottling the water that became known as Poland Springs in 1845; Saratoga Springs in New York was selling seven million bottles a year by 1856. Popularity was fueled by new glass-making techniques in the early nineteenth century that made the bottles more practical and affordable. Ponce de Leon water was analyzed as having .01 ppm of lithium. Natural lithia springs are rare in Virginia, though one, Wildwood, was developed north of Palmyra in the early twentieth century, when that area was reached by the Virginia Airline Railroad. Lithium bicarbonate was elsewhere added to water in the bottle. Lithium's "neuropathic abilities" came into prominence after medical studies in the mid-twentieth century. D. Wiley Anderson could bank on the good taste of his spring water. Scottsvillians came to the place on a weekly basis to get it. D. Wiley, Keith says, built a special rack for his truck to carry the bottles further afield, and eventually sold Ponce de Leon water in North Carolina, Ohio, and New York up until the mid-1930's. The architect and inventor had bigger schemes, too, and in September, 1920, ran an ad in a commercial periodical, "Doorways," for his property: "'Albevanna Ponce de Leon Spring,' eight room dwelling, 200 acres of land, beautifully situated near Scottsville, Virginia. Spring contains wonderful healing and other therapeutic properties, now ready for development. Just the place for a Hotel-Sanitarium; or the most exquisite home for a party of wealth desiring a health location�with exclusiveness; numerous streams and picturesque surroundings. Nothing else like it to be found. Price: $50,000." But when no "party of wealth" stepped forward, Anderson, in 1923, was drawing up his own plans for "the Albevanna Hotel�and Pleasure Resort." This ambitious scheme was never achieved, but has left memories and a few tangible reminders in the form of glass bottles. As Jack sums it up, "Horse liniment, whiskey, water, milk, cola, all bottled, marketed, and sold right in and around the small town of Scottsville. I know of no other towns the size of ours that can claim such a variety of bottled goods with their own hometown logo embossed on them. As we peer into those long retired Scottsville vessels one final time, we can't help but see the reflection of a diverse and proud past, and, we can hope a bright future." References: Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum |

|

|

|

Museum

Archive

Business

Cemeteries

Church

Events

Floods

For Kids

Homes

Portraits

Postcards

School

Transportation

Civil War WWII Esmont Search Policy |

||||

|

Scottsville Museum · 290 Main Street · Scottsville, Virginia 24590 · 434-286-2247 www.avenue.org/smuseum · info@scottsvillemuseum.com Copyright © 2020 by Scottsville Museum | ||||