Oral Historian: David Schumaker

Interview Date: 27 June 2006

Interviewer: Angela Nemecek

I was in the Marine Corps Reserve and afterwards, I became a marine.

What was your rank?

I started out in a PFC candidate's class and was promoted to 2nd Lt. before I went overseas. And during the war, I was 2nd Lt., 1st Lt., and Captain.

Where did you serve?

In the Pacific Theater.

How did you come to join the Marine Corps?

Well, that's a long story. I was in my fourth year at the University of Virginia School of Engineering, studying Civil Engineering, when the war broke out in 1941. And they gave me a deferment until I finished school. Then came January and February 1942, and the Marine Corps came to Charlottesville, recruiting for officers' candidate class. At the same time, the Tennessee Valley Authorities were recruiting employees to build the Paducah dam and the Fontana dam. I signed up to go to work on the Paducah dam, which was a very vital world war industry. I was working in the Personnel Placement Office at the time of the NYA (National Youth Administration). The head of that office, Mr. Kaufman, was a retired reserve Marine, who tried to get me to sign up for the Marine Corps. David said, "I'd rather work than fight."

Well, I went on and graduated from Engineering School on the 15th of June, and my deferment ran out on the 17th of June. And even though they had a letter from TVA, the draft board on the 20th of June told me to report for induction on the 26th. Well, that meant I was going in as an enlisted man.

I went back to see Mr. Kaufman and when we got all of the papers together, I was sworn into the Marine Corps on June 26th as a PFC and a candidate for officer candidate training. That is when I notified the draft board that I was already in the service --- I was already in the Marine Corps. Ten weeks later I was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant. Then I went through reserve officers' training school, and when I finished that, they sent me to Camp Lejeune for Combat Engineer training.

When I was in Combat Engineer training, they introduced us to demolitions. While we were doing demolitions training, the instructor told us they were looking for volunteers for a new school in Washington to train bomb disposal officers. It was a new field that had been developed because of the bombing of London. There were unexploded bombs there and someone needed to take care of them. They needed highly trained technical people to do that. Well, I had a pretty good background in fixing things and a good mechanical aptitude. Even though the training was pretty intense, the Marine Corps had not convinced me that I was a leader. But I figured I could work with my hands and do things myself. I was pretty confident, and I signed up for the bomb disposal school.

From there I went to Washington, DC, American University, to a 10-week course in bomb disposal. We had to learn to identify every piece of ordinance that the Japanese had, the United States, Great Britain, and Germany. We had to know how to draw and analyze each piece by memory as to how it operated and so that we could look at the markings on it and tell what was in it and how it worked and what to do to get rid of it. And could we move it or did we have to blow it up where it was. When we got through with that, they shipped us out to the Pacific.

What was the timeline of those events?

I reported for duty at Quantico on August 11, 1942. I graduated and was commissioned a 2nd Lieutenant on 17 October 1942. On the 24 October 1942, I met my future wife in Washington. In December 1942, I graduated from Reserve Officer School. I was ordered to Camp Lejeune for engineering training and finished that up in January but they had me waiting for something from Washington. It was in April 1943, when I reported to American University for bomb disposal training. I graduated from there on the 3rd of June and I was ordered to the West Coast for transportation overseas with some leave time in between.

I sailed from San Diego in July 1943, and arrived in New Caledonia the 23 July 1943. I went into a transient center there to await assignment into combat. We were there from July until September when we were assigned to the 3rd Marine Division, which at that time was stationed in Guadalcanal. We got there with our training and background and they didn't know what to do with us because they hadn't heard about bomb disposal at that time in the field. It was all new. But they finally assigned us to an engineering company.

We landed at Bouganville on November 1, 1943. I was attached to the 9th Marines as a bomb disposal officer but I was really part of the division. While we were in Bouganville, we were called upon to deactivate bombs. When they built the airfield, we had to get a bunch of duds out of there to clear the way for the airfield. And we had to go out in front of the lines several times to get duds.

Then they decided they needed to put us in Ordinance instead of the Engineering Division. So they transferred us to Ordinance where we worked for awhile. Then we came back to Guadalcanal the first part of January 1944 when the Army took over Bouganville and we moved back into reserve at Guadalcanal for retraining for the next operation. We were there during January and February in training and instructing troops in identifying bombs. While we were in Bouganville, the Japanese had bombed an ammunition dump at Guadalcanal and set it on fire and it burned. A lot of ammunition was damaged but not exploded. In March 1944, the Marine Corps needed additional space for a depot, and the only space that the Army would give them was part of this ammunition dump. So all of the bomb disposal people in the division were sent down there with some help clear out the area. We hauled out and dumped at sea some 700 tons of damaged ammunition.

At that time they decided that there was a bunch of new stuff and that we needed to upgrade our training. They flew us down to Brisbane, Australia, for a refresher course in the new weapons that had come out. While we were they, they gave us a week of liberty in Sydney. Then we came back to Brisbane and finished up the training and returned to Guadalcanal by way of New Caledonia.

In March or April of 1944, we boarded a ship to invade Guam. The 2nd Marine Division was supposed to invade Saipan, and the 3rd Marine Division was going to invade Guam. They had one division to back us up as reserve. But they had so much trouble in Saipan, that they committed that division to the 2nd Marine Division. So that left us without a reserve, and we had to wait until they loaded up one at Pearl Harbor and bring it out. While they were doing that, we stayed on board ship for 52 days waiting to go on to Guam. We'd sail west all day to make the Japs think we were landing, and at night, we sailed east. The 77th Army Division came out to back us up, and we headed to Guam on July 21, 1944. I don't know when we secured Guam, but it was pretty 'hot' there.

I went into Bouganville at H + 1 hrs., which is one hour after the troops hit the beaches. And I went into Guam at H + 4 hrs on D-Day. Somehow I survived, I don't know how, but I did. We had many beach mines to clear there. The Japanese had put out a lot of mines, but they didn't get around to putting fuses in them. So we just dug them up and moved them and put them in the dump. We worked pretty hard. We went in with a Sergeant. All the tools I had were on my back. I didn't have any equipment to work with. I had more than I had at Bougainville, but I didn't have much at Guam.

Meanwhile, back in Washington, the people in Washington were pushing info out, and the Divisions were getting familiar with what was going on and how they needed us. So after Guam was secured, and they flew all of the bomb disposal people back to Pearl Harbor. They put us out in a bunch of tents in a field and reorganized us into two bomb disposal companies. One went with the 5th Corps, and one went with the 3rd Corps. I ended up as a platoon leader for the bomb disposal company. We were there from October until January 1945, organizing, training, and getting equipment. Each squad had a truck and a good toolbox full of tools to work with. It was the first time we were really organized to do the job.

My company went back to Guadalcanal, and one platoon went with the 1st Marine Division and one with the 6th Marine Division. We went into Okinawa, and the other platoon went to Iwo Jima. We landed in Okinawa on Sunday, April 1, 1945, but I didn't get on shore until D+1 because the boat broke down. So I was there until it was secured, and then they sent us back to Guam. While we were there, they ended the war in 1945.

H stands for 'hour,' D-day means the 'designated day.' June 6th is D-Day in Germany when we landed on Normandy Beach. In Guam, D-Day was the 21st of July. And H-hour was 8 o'clock. So that meant that I landed at 12 o'clock that day (H+4).

They sent me home from Guam on a chartered merchant marine. I don't know where they found it, and they didn't have any fresh water on board. Their fresh water equipment had broken down. They hadn't cleaned the boat up in months, and all we had was drinking water and enough to cook with. The flour had weevils in it, and the beds had bedbugs. It was an awful trip from Guam back to the West Coast. When we came under the Golden Gate Bridge, it was the happiest day of my life. On 13 October 1945, we landed in San Francisco.

I stayed at the Top of the Mark on Saturday and Sunday nights. Then on Monday, we went to Oakland to board the train to Chicago. It was 4 or 5 days between Oakland and Chicago. We spent the night in a barracks there that they set up for transient troops. I took the George Washington from there to Charlottesville, and my folks met me. We lived in Scottsville at the time. It had been 30 months since I'd seen my family.

When you were over in the Pacific, were there a lot of casualties?

Oh, yes. Not so many on Bouganville, but when we landed. We had several bad situations on Bouganville. Our landing beach and the small island just to the right of it - they bombarded it pretty heavily, but they didn't get all of the guns. There were some howitzers that were aimed down the beach and they wrecked 3 or 4 boats and killed quite a few people before we managed to get them.

Later on in Bouganville, after we'd pushed in and got up on the mountaintop to try and get the high ground, we ran into quite a bit of opposition. But I wasn't up there - I was back there where all the bombs and shells were dropping. Most of my work was in the rear, but we were still subject to air strikes. We were there to take care of the bombs that didn't go off. You see, after the troops go in, you have to bring in all of this equipment and you have to have a place to put it. So it's when you're clearing those areas that you run into that stuff, and it has to be eliminated. We'd either go in and put TNT on it and blow it up right there. Or if it would make too bad a hole, we took it away. For example at Okinawa, we were given the job of clearing the landing strip on the island of Ie where Ernie Pyle was shot. (Ie Shima is just west of Okinawa in the Ryukus Islands). The Japs had planted fifty 7500-pound bombs with the tail down and nose up. The fuse was in the nose, and so if you hit it, it set the bomb off. We could tell what they were and took the fuses out. We didn't have to blow up the bomb, because if we blew up the bomb, it would make such a great big hole that it would take two truckloads to fill it and pack it in to rebuild the airfield. But we could pull the bomb up, pack dirt in the hole, and have the field operational soon. We hauled off all kinds of stuff there.

Did you ever encounter anything that you didn't know what to do with it?

Yes, several things. So we'd clear the troops from the area and blow it up right where it was.

Were you ever really scared?

Oh, lots of times. Lots of times.

Were you awarded any medals?

Yes, I got the bronze star in Guam.

I know that you wrote letters to your family and your future wife because it's written there in your journal. About how often did you write?

It depends how much time you had. When we were sitting at Guadalcanal and waiting to do operational training, we had a lot of free time and you could write. A lot of it depended on the mail. Of course, I wrote to my girlfriend regularly. Sometimes it would be a week or two and you wouldn't get any mail. Other times you'd get 8 or 10 letters all at once. Other times you'd go get the paper out to write, and it would be so damp that you couldn't even get it apart. The humidity was humongous out there.

At Guadalcanal, while we were waiting to go into Bouganville, we'd have movies set up. The seats were coconut logs you'd sit on. They'd have movies at night, and you'd go out with a pith helmet and a poncho. You'd sit on the coconut log in the pouring down rain and flooding your shoes. It was just rain, rain, RAIN. Everything would get saturated and mildewed. A lot of people got jungle rot, fungus, and tropical diseases. It was terrible!

Did you get sick?

No. Well, I had diarrhea a number of times, and the only time I really got sick was in Guam and I came done with dengue fever. I thought I was going to die, but it only lasted about ten days. It's something a mosquito transmits and you have an awful lot of pain. You ache all over with high fever.

Did you have a medic?

Every small group had a Navy medical corpsman. The Marines don't have any medical people, and all of their medical people are arranged by the Navy. There are Navy doctors attached to the Marine Corps, and they have a group of medics that they call 'corpsman.' There are a lot of them around. And there are clinics set up when you go ashore. They follow along and pick up the wounded, and of course, the grave registration are picking up the dead, transporting them, and burying them. There were always medical corpsmen around.

You talked a little bit about watching movies or trying to watch them…

Oh, we watched them all right, whether we could see them clearly with the rain or not. There was nothing else to do. They had movies almost every night unless there was something else going on. It was the only entertainment we had: movies and reading books. I think I read a library full of books especially aboard ship. I read every kind of book I could get a hold of. Mostly novels, a few mysteries… I've always been an avid reader.

When you were in Guadalcanal, there was really a lot of down time while you were waiting for training…

You see they captured Guadalcanal in 1942-1943. By the time we got there, it had been secured and they were using it as a staging ground. So they got the 3rd Marine Division in there and started training them for the next invasion, which happened to be Bouganville. Bouganville was one of the places where they needed an airfield so they could bomb New Guinea and from there work their way up the Pacific. It was an island-hopping situation.

In your journal, it seemed like soldiers drank quite a bit…

Oh, yes. That was another way to pass time. There was always plenty of beer…not much hard liquor, but lots of beer.

How did you get the beer?

The Post Exchange service brought it in, and the military just brought it by. That was part of taking care of the troops. You had a ration, and you got so much a month and a week.

What was the food like that you ate?

It was awful most of the time. Dehydrated eggs, dehydrated potatoes. The potatoes could be reconstituted pretty well, but the eggs, well, I never did figure out how to make them fit to eat. The only fresh meat that we got on shore was mutton from Australia. And we had what we called 'acorn butter' which was just like putting axle grease on your bread. What the cooks could cook up, they could make pretty good bread and hotcakes. But when it came to anything hard…and canned meat: we ate so much SPAM that it was 10 years after the war before I could eat SPAM again. Of course, in combat we had rations that were packaged for us, and they were terrible. C-Rations you would get 1 out of three meals that were pretty good. The other meals weren't fit to eat…corned beef hash and all kinds of stuff. K-Rations had a lot of chocolate in them. And every ration had cigarettes, chewing gum, and toilet paper. Nescafe coffee and some sugar. If you were in a situation where you could build a little fire, you could take your canteen cup and make a cup of instant coffee. But lots of times you just had to drink water out of your canteen.

We looked forward to getting back aboard ship, because the Navy lived just like back in peacetime: clean sheets to sleep on, fresh meat, ice cream, fresh eggs…. The enlisted men may not have had it as good, but officers on board ship would "eat high on the hog." The enlisted men ate well, but they didn't have it served quite like we did.

Were there pranks that people played, sort of 'cutting up?'

No, not a whole lot of that. No.

Was the atmosphere fairly serious?

No, we told jokes and sang songs. We'd have a drinking party and sing all kinds of songs, tell stories and share experiences. When we were not in combat, it was not too bad. It did get boring. The officers had to spend a lot of time censoring mail. All enlisted men's mail going out had to be censored. We spent hours just censoring mail.

Did you have guidelines for censoring mail?

We knew that there were certain things when we were in combat such as where we were and where we were going that had to be stricken out of the letters.

I know you kept a diary - how did you decide to keep that journal?

I'd kept a diary through high school. Off and on, I've kept a journal all of my life. I've got 4 or 5 books stacked away that I kept in the 1980s. The diary that I kept in high school I ran across when we were leaving Scottsville to come down here. I had written in in shorthand and can no longer read my shorthand. So I just threw it away.

I tried to expand on the diary I kept in WWII. I tried to make it worth something to other people instead of just me. There was a regulation against keeping a diary and there were just certain things you couldn't put in it. So that's why mine was so brief-- it was more or less to keep some timelines so I could go back and fill in from memory. So that's what I did when I came home and initially transcribed it. I wrote it then on the computer and was able to italicize notes and expand on it. The other people who were reading it then could get something out of it. Since then I managed to get some pictures, and my daughter put some of those in there. She worked with the graphics department in NCA in California for years and had all kinds of graphic equipment.

Now some of the pictures were pictures that you took.

That was another thing that was unusual. Not everybody could have a camera and take pictures over there. Only photographic people were allowed to do that. With this bomb disposal work, they furnished us with 35 mm cameras to take pictures of any new ordinance that we came upon. We'd get lab people to develop them and send the pictures back to Washington to distribute. And that's why I had a camera. By having a camera, I was able to take pictures of anything I wanted to. I realized that I couldn't get all of this stuff developed. So I managed to get a hold of a day load tank for 35 mm film and chemicals. We had to trade for the chemicals. I could develop the film and keep the negatives, figuring I could get them printed when I got home.

I didn't get around to it for years, as I was too busy with my job and raising a family. By then they had set and I couldn't get them printed with modern day processing equipment because they needed a flat negative. But I was bound and determined to find some way to print them. Finally about 5 years ago, I went and bought photographic darkroom equipment and set it up in my shop in Scottsville. Then I started printing some of them. But about the time I got started doing that, the drought came along, and we didn't have enough water to process the prints. So that project sat idle for a year or two. Then about three years ago, we were at an Airstream rally in Florida, and I ran across someone who had a scanner that would do black and white negatives or slides. So I bought it, but I couldn't figure out how to operate it for about 6 months until my daughter was back east here and explained what the problem was. So I've scanned lots of negatives onto the computer and have lots of pictures I didn't have before. And I have them on CD. But I've got lots more WWII negatives to scan.

How many pictures would you say that you have?

Thousands of them. But there weren't many of them worth anything because you need controlled temperatures with photographic materials. So in that 90-100 degree weather, the water would be so hot that the gelatin would come right off the negative. In any event, the negatives are all quite grainy, although some are better than others. But that's how we could get film - we could bum 100 ft. rolls of 35 mm film from the camera people who took movies of the operations. Then at night we'd get under a blanket, cut the film, and load it into the cartridges. In those days, you could take the end off a cartridge and reload them.

So how did you know about photography?

I read about it. I've been an avid reader and researcher for information and knowledge all of my life. Every time I find something new, I want to know how it works. I got my first computer in 1987 and have been working with it ever since. There are still a lot of things that I don't know, but I keep learning every day with it. And I'm an accomplished carpenter and I've got all sorts of photographic work that I've done since I came back from overseas. Everywhere we lived with the military, I set up a darkroom and took pictures of the family and printed them. I couldn't afford to pay someone work on my car, and so I did all of the mechanical work on my cars until they became electronic and then I had to give that up. Anything else that came along, I just learned how to do it.

I got my basic knowledge of equipment out of Sears and Roebuck catalog when I was a kid. I went to a two-room school just east of Scottsville. In those days, they got a box of books about that square from the State Library in Richmond, shipped in railway express, with an assortment of books in it. And while that box of books was there, I'd read everything in it. Either at school or at home I'd read by oil lamp.

I picked up all kinds of information from that, and when I didn't have a book to read, I could study the dictionary. I learned how to pronounce words, how to spell words, and in the sixth or seventh grade I was No. 7 in the State Spelling Bee over at John Marshall High School. At home at night, I'd get the Sears Roebuck catalog out and look at all of the equipment, read the description of it, how it operated, and try to learn what it was all about. I educated myself out of that.

My dad never went to school a day in his life. He learned to read and write after I came along. I was the fifth of nine children. My mother died when I was 6½ yrs. old and left 9 children when she was aged 35 yrs. All grew up to adulthood and were fairly successful. I had another brother in the Marine Corps, and he and I are the only two left. He's 80 yrs. old - he was 5 weeks old when my mother died of a brain tumor. So he put 20 years in the Marine Corps and I put 25 years in.

After the war, did you come back to Scottsville?

Well, I came back to the States, and they had me report back to Camp Pendleton, CA. But my leave address was Scottsville. So when I got to Scottsville, someone from Washington looked where I was from, and they changed my orders to Quantico. So I reported into Quantico. But meanwhile, my future wife, Mary Love Lewis, had always said she wanted to travel. She had hoped to marry someone in the Foreign Service. When I came back, we became engaged in October after I got home and made arrangements to get married in February. She quit her job with the FBI and went home to Patterson, GA. We were making plans, and I was the training area maintenance officer at Quantico at that time…still a reserve and subject to release and active duty. In December, I got orders into inactive duty. With nothing to do engineering wise in the winter - I really didn't expect to get out of service before June. So the adjutant said, "The only way we can cancel these orders is to have you apply for a regular commission. It takes 6 months for that to come through." So that's what I did.

We went ahead and got married on the 17th of February and overseas, not being able to take leave, I'd accumulated 45 days of leave. They said as we reserves went out that they weren't going to pay us and that we had to use up our leave. So we had 45 days on our honeymoon. A lot of that was getting ready to go down (to our next post)…

From February to May, when the regular commission came through, we were living in quarters at Quantico. We discussed it, and she decided that she wanted to stay with me in the Marine Corps. So that's what we did. And she got to travel all over the U.S.

So she had been working with the FBI - what did she do?

She was in the highly secret code room, where coded messages came in and went out. She helped decipher them and encipher the codes

Did you just meet her when you were at Quantico?

When I was a junior and senior in high school, I got to work in Washington for three summers, including one year after I started college. I'd met up with her cousin who had worked with my brother. I went up to visit the cousin the week after I was commissioned, and he said, "I've got just the girl for you." Mary Love had just been up there a few months, I think, and was staying with an uncle about 20 blocks across town. So he went over and got her and introduced us.

So she decided to stay with you wherever you might be stationed?

Yes, I accepted a regular Marine Corps commission in May 1946, and pretty soon they gave me a choice of going back overseas or of going to Barstow. So they transferred us to Barstow, CA, out in the middle of the Mojave Desert. It was dry and hot, and we enjoyed it, but we were glad to get out of there. We were there two years (1946-1948) and then came back to Camp Lejeune, NC (1948-1951), and then in 1951 we were back to Camp Pendleton, CA (1951-1953). Then she came home for a year while I went to Japan and Korea. Then we went to Paris Island for three years and from there to Washington, DC, for three years. In 1960, I went from Washington, DC, to Troy, NY, for a year and got my Master's Degree in management. From there we went to Albany, GA, for three years, and then back to Washington for two years. She stayed there while I went to Vietnam. But I was only in Vietnam for three months due to complications of thrombosis phlebitis. They shipped me home, and when they realized they couldn't cure me, they put me out on retirement in March 1967.

That was when you were getting all of the blood clots, right? What caused that?

Well, I had no idea. The two years I was in Bethesda in 1966, I had an outstanding doctor there and he treated me and talked with me and advised me. He explained that when you get in a tough situation, the body prepares for fight or flight. The flight is adrenaline and the fight - in case you bleed - is a blood clot. So the clotting mechanism goes into effect. So when I got in a stressful situation, my blood clotting system would perk up. Apparently, it overdid it in each case and I had blood clots all along until my last one in 1991. I was in Calgary, Canada, on our way to the West Coast, and I went into the hospital with what they called 'shower clots' in the lung. I was in the hospital for a week until they cleared it up, and I took cumidin for about a year, and then I went on aspirin and took that up until just a short while ago. And I haven't had any more blood clots. We moved back to Charlottesville in 1992.

But you had two or three clots in Vietnam, right?

I had two clots when I was in Vietnam. After the second one, they figured the only way they could keep me from having a blood clot is to put me on anticoagulants. But they couldn't keep you on anticoagulants in a combat area. So they had to evacuate me from Vietnam and sent me to Bethesda. This doctor got a hold of me and held me there until he got it cleared up. I went home in December 17 and threw a clot in my lung. I went back in the hospital, and he said "We can't do anything but keep you on this stuff." So they put me out on retirement in March 1967.

How old were you at that point?

I was 47 in 1967. So I worked for a mortgage company for about a year, and couldn't put up with that. Meanwhile, I had been doing some substitute teaching, and so I applied to teach school. So I got a job teaching 8th grade boys' industrial arts in Falls Church, VA. We were living in Springfield at that time, and we stayed there until both of my girls graduated from William and Mary and my son was in the University. We quit, sold our house, moved into our trailer, and started traveling. We went to Scottsville to our old home place - Dad deeded it to me in 1964 to take care of him and my stepmother and brother. So we went down there and after a year decided we would build a house on the back side of the property. My stepmother lived on the front side, and my brother lived on a little trailer there. That was our residence for the next 16 years - and six months of the year we were on the road doing Airstream trailer travel. We spent time in Florida and traveled to all of the continental states and all of the provinces of Canada once, and some of them twice.

Meanwhile one of our daughters, who finished William and Mary, was in California and so we made several trips out there. We spent one winter out there with her in that trailer on a campground. We were Airstreamers for 38 years and finally gave our trailer to our son on Labor Day weekend of 2004. And we moved to Mechanicsburg in November 2004. We had already been on the waiting list for this place since before it opened in 2001. But we were too far down the waiting list and it took three years to move in here.

Last time I went into the hospital with a blood clot problem we were in Calgary - while we were living in Florida. So we decided we'd better be near our kids, and so we moved back to Charlottesville. We still had the property in Scottsville (not a house yet though), and I had a big workshop there - woodworking, welding, mechanics. I did all of my work there. And that's where I set up my photographic shop. I kept it until 2002 or 2003, and finally sold it. I was getting tired of putting up with the renters. So I sold it, and had a year to get out of my shop. In October of 2003, just as I had things ready for the auction sale, I came down with shingles. And that knocked me down for months before I finally got up. I still take medicine for shingles - post-herpetic neuralgia, they call it.

My wife is over in the Health and Wellness - she fell and broke her hip in April 24, 2005, right after we got here. She was in the hospital for two weeks, came through rehab, and somewhere along there developed a staph infection. She had to go back into the hospital and was in and out of the hospital from then until August, over here until September, then over here until March, back here in March, and broke out again and is back in the hospital. She's over there now with a full-floating femur - they had to take out part of her left hip bone.

This is a continuous care, retirement community, and you go from independent living to assisted living, to health and wellness with nurses, and then out the back door. So she's over there until she can come back here. She's running around in a wheel chair, and so she comes over here quite frequently during the day. But at night they take care of her. And she has to wear a big brace when she stands up. Certain things they have to do for her. I could do it, but there is not point in me doing it - they can do it better.

Did you keep in touch with the people you met through the military?

I kept in touch with some that I met again after I left the service. There is one thing that you read so much about units getting together for reunions. I was in a very strange outfit - I was never in an organization where you worked together as a unit and fought as a unit under all sorts of situations that bonded you together. Most of my work was done independently with maybe only one or two of us. All of them were reservists, too. After the war there were only two in my retired officer's class that stayed on active duty and became regular Marines. And I never ran into them in all these years.

I worked that way through Bougainville and Guam, and then we organized our unit but weren't together very long. You didn't send a whole unit out to defuse a bomb - you pretty much sent only an individual or two to do that. It was the nature of the work that we didn't work together and bond in groups.

Then after the war, we moved about so much. We kept up with a lot of people that we worked with after the war for years until they slowly died off. The last one just died in December. There are none of my buddies left that I did duty with -- that I know of. But then there are not many people, who live to be as old as I am or as alert as I am. I don't have a lot of physical strength though.

How do you think your experiences in the War affected the rest of your life?

I don't know - hard to say. I learned a lot.

Do you think you would have been in the military if it hadn't been for the War?

No. I had no intention of going into the military. I had no desire. I wanted to build bridges - I went to engineering school so that I could build bridges, dams, and roads. I was all set to build bridges until I went through that experience in Quantico - and this is something that people don't believe - I have a very strange personality in that I am very sensitive and have a very poor background. I grew up in a family that didn't know anything - had no education and very little contact with outsiders. And almost everything I knew I either got out of a book or I picked up listening to people. Lot of stuff I picked up from kids I grew up with didn't make much sense.

In engineering school, I got an engineering degree but they had no liberal arts courses at all except English - and it was only aimed at writing reports. I learned nothing about economics, except the little bit I got in high school, and I just lucked into business administration in high school. That was a big help to me. But a lot of things I didn't know - like how to get along with people. I didn't know how to get along with people and to work in society.

The Marine Corps has a system of training where everyone comes in and is broken down to nothing and builds them back up to Marines. They can do anything and are leaders. They didn't build me back up after they tore me down - I didn't have confidence in anything except what I could do myself. When I got out of there and went to Camp Lejeune, I never felt like I had the ability to lead or show people what to do. But I could do it myself. This was the situation that I was in all through the war and after the war even. I had no confidence except if I was given a job to do myself, I knew I could do it. I had problems getting along with people until the epiphany - and by this time, it was too late - came to me at Camp Lejeune in 1949. I was a company commander, and I figured I'm a darned poor company commander and don't know what I'm doing. Just give me a job and I do what I can… They went through all of the records and found out that I was one of those who had not taken any of the tests that the military gave soldiers as they went into service. So they sent me over to Division Hqs to take the tests - general military subaptitude test: mechanical aptitude, IQ, and all that stuff. Apparently my IQ was up close to genius level, mechanical aptitude - I maxed and it was the first time the Marine Corps had ever had a maximum score on it. I realized that a lot of my trouble was that people couldn't always see things as I saw it. I had the intelligence to understand that they didn't understand, but I didn't have the sense to realize that that they didn't understand because they didn't have the same intelligence that I had. I thought everyone had the same sense that I did.

And after the war, most of the soldiers who stayed in the Marine Corps did not have a degree. They weren't that educated. And I missed being in combat in Korea because I had a degree in engineering. Six weeks before Korea broke, I was in Camp Lejeune, and had an engineering company. They needed to have a school on base where they taught engineers, plumbing, electricians, carpenters - basic engineering. And they need an engineering officer out there. They had two in the Division that had a degree and they sent me out there instead of the other guy. Six weeks later, my old company and whoever took over for me as its commander, went over to Korea and up to 'frozen' Chosun. Half of them didn't come home just because of that.

There were several other situations that happened because I had a degree. At Camp Pendleton in 1952, they sent out a call for Marine Major to go to Kirtland AFB in Santa Fe, NM, and go through atomic weapons school - to learn how to figure out the effects of an atomic bomb and how to use them in case we needed to do so. They had two in the Division at Camp Pendleton: the other guy was up where he could make a decision and they sent me. I got into atomic weapons and later biological and chemical warfare, and so I went into that, too.

I had the education that others did not have. And I realized that I was working with people, who didn't have the know-how or the grasp of stuff that I did. By knowing that, I was able to work with them. Before that I would get in all sorts of trouble and not know 'why'. I was misreading things and it looked simple to me and would go ahead and do it. And they still didn't know how to do it. So I'd get into trouble because they weren't learning, too. Some of the people that I worked for resented the fact that I knew what to do and did it.

So you had a rather atypical experience in the military?

Yes, I did - most atypical. I did not have a typical military career. All through officer's training, I just barely got by with the military part. But of all of the other material, I practically got A+ on it. Anything having to do with bookwork was something to learn to do this or to do that. Operating the equipment, disassembling it and putting it back together… But when it came to close order drill - turn left, turn right, and all of that stuff- I just managed to get by. It just didn't interest me.

And I stayed in because by that time I had missed the opportunity to take the professional exam one had to take when you got out of school in order to operate as an engineer. And I didn't know if I had sense enough to get back to that level and pass the exam. The military had just convinced me that I just wasn't up to par. So I stayed in the service because I had a job and a place to live. Most unusual…

People who listen to this are going to wonder what it is all about…who IS this character? But that's the way it is…

So when you had that epiphany, after they gave you all of the tests, what year was that?

In 1949. From then on, I didn't have nearly the trouble that I had had up to that point in time. I still had trouble getting people to work for me, because I tried to figure that they had sense enough to do the work, but didn't want to do it. I pushed people, and I got work done. I had a very successful tour in Paris Island, where I was the maintenance officer in charge of the maintenance and upkeep of the whole base and was there three years. We reduced the manpower from 1500 down to 700 in that length of time, and we did more maintenance than they'd ever done--all because we got organized.

And when I went to Albany, GA, to take over the overhaul and repair shops - we repaired all of the Marine Corps equipment that came in from the field. I was there three years, and HQS Marine Corps gives out the annual work load: you do so many trucks, so many this, so many that. At the end of the first year (1961), it was the first time since the place opened in 1956 that they had done their annual workload. We finished up in May and had to ask them to let us take on next year's workload. All because I put them to work, and I was everywhere.

You can't sit at your desk and expect things to operate. A boss, who sits down at his desk all day, has stuff going on that he should know about. Of course even if an officer got out there, he still might not know what's going on. That's where I had an advantage: I was a mechanic, a photographer, a carpenter, and could do most anything I wanted to do. And if I ran across something I didn't know, I'd ask someone, who did know, and make sure I learned something about it.

I'm a most unusual person. And I'm not a mean, ornery colonel. I'm pretty well liked around here, and they call me "Colonel."

Well, I haven't told many people except you about how the Marine Corps tore me down and didn't build me back. But that's been the key to my life. My whole life hinged on that aspect of it: what I managed to do and what I didn't manage to do. I could have done a lot more in my life if it hadn't been for what I had to put up with --- the stress I was under before I really began to figure out what the problem was. It probably caused all of these clots and other problems that I had. It was way down the road before I found that out. If I'd had a little more confidence further back down the line, I wouldn't have stayed in the Marine Corps. But I served my time, and I did more than was expected of me in most cases. I never shirked my duty, and wherever I went, people knew that I'd been there.

I met up with a Sergeant at a funeral in Scottsville, who I knew had put 25 years in the service behind me. When I finally met him and he got to talking and said, "You're the Colonel Schumaker I've been following all over the Marine Corps. I followed you for the last 15 years and everywhere I went they said, 'I'm glad that Schumaker is gone!'" Because they knew and the Marine Corps knew that I'd been there. But when I got on the parade ground - forget it - I managed, but just barely.

If you had it to go back and do over, would you stay in the Marine Corps?

Well, if I didn't know any more than I knew then. But yes, I think so - it's worked out because I would have made General in the fall or summer of 1967. But if I'd stayed in Vietnam through that tour, chances are my career would have been ruined and I wouldn't have gotten anything out of it. Because there were two or three Colonels, who worked for that General before, and they had their careers messed up. He was a character to work for. Nobody liked him - he was a bigger S.O.B than I was. As it was, I got surveyed out, and while I was in the hospital, the guy explained to me about my troubles and said, "If you don't change your way of life, you're not going to last 5 years." And I realized that was about what was going to happen, and ever since then, I've avoided that kind of pressure. I did not go for a second career in something with more stress than teaching school. That was a lot of stress, but something I could handle. Because of that I have been able to survive and live to this age. I wouldn't have made it, I don't think if it hadn't have been for that. And I've got a wife of 60 years who is with me still.

So you married your wife in 1946, right?

We celebrated our 60th anniversary last February (2006). I'm 87, and she's 86. Right now she's in good health except she doesn't have a hip joint. We're hoping that by October they can decide that she's definitely free of the staph infection and maybe go in and give her an artificial hip. We're hoping.

There's no way that they can be positive that the staph is gone. She's been on IV antibiotics for 6 weeks after she got out of the hospital the first of May 2006. And now she's on 6 weeks of oral antibiotics. She's been free of the staph as far as her blood tests show since March 25th. With an infectious disease, however, the doctor and the surgeon have to agree that it's safe to go in there. If the staph is still around, it is attracted to metal just like a magnet. So once it (the artifical hip) gets in and gets a staph infection, they just have to go in there and take it out.

I think the orthopedic surgeon is hoping that by the time they get around to it in October, she'll decide that she can make out without it - just by using that brace that goes around her waist and down her leg with two big clamps. She can walk with the brace on, but it's a pain.

You're really good with dates, I've noticed.

I have a really good memory. With most things, I do. My granddaughter just got married back in January and I don't know what day she got married on. I think it was the 6th of January but I'm not sure.

That's pretty good!

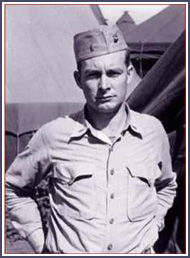

D.W. Schumaker Awarded Bronze Star

The Scottsville News, 15 March 1945 (p.1):

Marine Lieutenant David W. Schumaker, son of C.W. Schumaker, of Scottsville, has been awarded the Bronze Star for meritorious

achievement in action against the enemy on Guam. Major General Maxwell Murray, U.S.A., recently presented the decoration at ceremonies held at a Pacific

base.

While engaged in clearing the beach and reef, Lieutenant Schumaker, bomb disposal officer, came under enemy fire. Upon determining

the enemy position, he and his assistant advanced and in the ensuing fight, killed two snipers. Three days later he was ordered to

Cabras Island to clear the causeway of obstacles. He cleared this area with such skill and speed that it greatly aided the campaign.

A graduate of Fluvanna High School and the University of Virginia, Lieutenant Schumaker entered the Marine Corps in June 1942. Veteran

of Bouganville campaign, he has been serving overseas since June 1943.