Oral Historian: Raymond A. Grandstaff

Interview Date: 12 July 2006

Interviewer: Angela Nemecek

Would you state your full name and birth date?

Raymond A. Grandstaff. September 27, 1923.

What branch of the service did you serve in?

In the Army.

And what was your rank?

I was a sergeant and then we lost that whole company. And so I started back over, and I ended up as just a private first class.

Where did you serve during the war?

Italy and France

And I heard you say before we started the recording that you spent a lot of time by the water? Where exactly were you?

Well, that last month, I was attached to the transportation corps. But that was after I left Italy and France.

How did you come to join the Army? Were you drafted or did you enlist?

Well, I was going to enlist with my brother, and we went to Richmond to do this and they took him and said I was a half-inch

too short for the Navy. So they sent me home and told me that I'd get a letter from Washington in two weeks. That they'd get

this waiver and then they'd take me. But they just wanted to separate us.

How tall were you?

I'm 5' 3 ½".

So they said you were half an inch too short?

Yes.

So your brother was in the Navy?

He was on the Yorktown. I had 5 brothers and they were all in WWII.

Were any of them killed?

No, they all came back. My oldest brother (Henry, Army) was in Africa, and he was putting up communication lines, and he was up there

pulling wires together. All of a sudden he just went swinging like that back and forth, and he said he turned around and looked.

There was a dud --- the shell cut the pole in two and it didn't go off. It was a dud.

My brother (Thomas, Navy), who was on the Yorktown, well, he worked in the boiler room--the number two boiler room and the number three

(boiler room) was hit. And his relief had just come done and relieved him and he had just gotten back into quarters when a

Jap suicide plane went down the chimney and exploded in the fifth deck down and killed everyone of them. He had just left his post.

(Raymond's other brothers in WWII were James, Navy; Charles, Coast Guard and Air Force; and Paul, Navy)

What was it like when you first joined? Where did you go for training and all that?

In Abilene, Texas. I trained with the 12th Armored Division down there.

About how long were you there?

I was there long enough. I went through non-commissioned officers school for which I moved from Texas to Little Rock,

Arkansas, and took the school there. And then I went back to Texas. When they called the Armored Division up, I finished on

April 9th. We came to Charleston, South Carolina, and that's where I left for overseas.

|

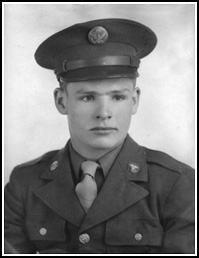

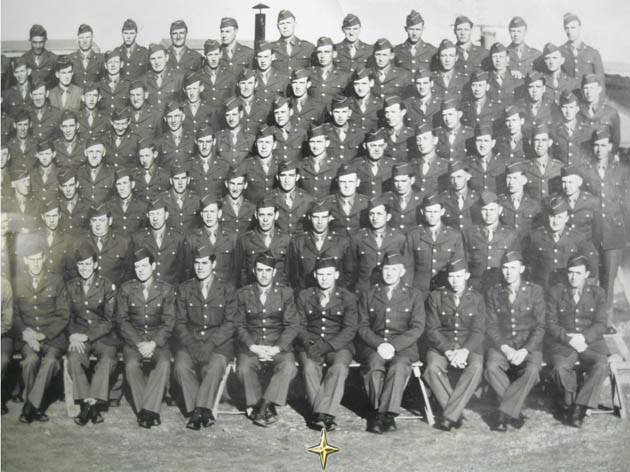

| Raymond Grandstaff (seated above the star) and fellow

graduates of Army basic training in Abilene, Texas, 1944. (Photo from the Raymond A. Grandstaff Collection)

|

What was the training like?

Everything! We crawled the infiltration course. It was just like that box right there - that's the course. And we came down

this side and there was a big ditch dug. And that thing was full of mud and water. I was short anyway and I had to hold my head

back like that to wade through that stuff. And then we crawled up over that thing, and as we crawled up on that, the machine gun

started. And we climbed right under the machine gun. One boy got killed on that thing. Somehow or other a bullet just went

down and went right through him. And it killed him right there. So shut that point down and covered it up and built another one

while I was still there. It was just a bad bullet. And I never heard of that anywhere else but that one time.

Was he part of your company?

Yes. See, there were four platoons, and I was in the third platoon. And the boy that this happened to was in the first platoon.

And we turned - I think I told you something about the hand grenade? It might have been one of those boys up there in Ohio - the

last one. But anyway, an instructor and two (soldiers) went into the pit. And they had those pits lined up with a barrier in

between and in front of them. That's where we learned to throw the hand grenade. Your hand was on the hand grenade like

this and you reached up and pulled the pin.

And he would say, "You hold it! Don't turn it loose." And you couldn't throw it like you throw a ball. You just had to heave it

up like that. And this boy heaved it, and he did it once with his fist clenched. When his hand came back, he still had the hand

grenade. And he did it again, like the instructor said but he couldn't turn loose of it. He said, "Oh, no!" He had gripped it

so tight that the instructor took both hands to loosen it up and get his hand on the pin so it wouldn't raise up. You only had

three seconds to do that before it went off. He got it away from the soldier, and he sent that boy out of there.

We had all kinds in the Army, I'm telling you. Another time, we had to go up on this hill and rescue some wounded. And this was at

midnight, and we came around this hill. We couldn't see anything and ran right into a fence. We had to get this wounded boy across

the fence, and just 2 feet away from the fence, it dropped off just like this table. We all fell down the bank. One boy broke his

ankle, and the rest of us were all scratched up. There were two of us for each of the wounded, and we had to get them out. We

finally struggled through the night and succeeded.

Another time, they woke us up at 2 o'clock in the morning and told us that it was time to get up. We're moving up this great big

mountain, and at the top it was really flat. We were supposed to build a big bonfire, and we just got it lit when here came the

biggest storm. We nearly drowned! When we got back to the camp, all of our tents and all of our supplies had washed away. We

had a terrible rain that time.

Where were you when that happened?

I was in Texas taking my basic training. We learned a whole lot!

You said that you left for overseas from Charleston, S.C. Where did you go first?

We went to the Mediterranean to the isle of Sicily. We couldn't get into the port because the Germans had scuttled enough ships

that they cut off everybody from getting into port. So the United States had to proceed at cutting enough of them up so that a

ship could get through. We waited outside the port until they did that, and then we came into port and docked.

I probably can't remember all of where we went, but we went to Sicily to clean up where the Germans had blown everything up.

That volcano (Mount Aetna aka Etna) was ready to erupt at any time, and so we had to do what we had to do and get out of there. It was

too dangerous to stay any longer. Three days later, that volcano erupted. But we had left there for northern Italy - and never went back to

Sicily. We joined up with the 3rd Army somewhere up in Italy, but never knew where.

There weren't many people left on Sicily, and there were ancient houses built up the sides of that volcano. And when the

volcano erupted, it just took everything right on down the mountain. I think it's the biggest island in the Mediterranean.

So when you left Sicily, you went up to northern Italy. Did you see a lot of combat with your unit?

Well, I don't know what you call 'a lot', but one particular place still stands out in my mind. We had surrounded

a farmhouse, sitting up on a hill. I can still see it like it was yesterday. That house sat up there by itself, and there

wasn't any shrubbery around it. And we were supposed to take it. We tried to surround it, but we didn't have enough men. We

only had 30-40 men, and they must have had half an army in that place and all dug in. They had trenches all around that place.

The commander had the radio and told us what we were going to do. This one outfit on the far side started in, and the Germans

were waiting for them. I don't know how many were killed, but the Germans killed a bunch of them. When they started shooting at

that outfit, we did not know that they were surrounded completely by German machine guns. We started with approximately 40 men,

and I think we came away with only about 15 men. We had men pinned down everywhere. Finally they had to call in the Air Force

to blow up that house and keep the Germans from killing all of us. That was one of the closest shaves that I was in until we got

to Longhorn, Italy. That was down at the far end of the Mediterranean Sea.

|

| 100 Lire, Allied Military Currency for use in Italy, 1943

(Raymond Grandstaff Collection) |

When we finally got away from Italy, then they moved us to Marseilles, France. They kept us so we didn't know anything; just

'do what I say.' And that's the way we operated. I only knew what my local outfit was doing. And if we lost radio contact with

them, we just had to wait and hope we could get back with them. It happened a lot, and we just had to do the best we could do.

You just had no choice. One thing I'll say about the U.S. Army then, when they took something, they kept it. It's not like it

is today.

In WWII, we had 14 million men under arms. That was a lot of people back then. Now 14 million men is just a drop in the

bucket of what you could put in if you drafted men. But now it's an all-volunteer army.

Do you think that's part of the problem - do you think a draft is helpful would be helpful in winning the war?

Well, it would just give you more people. But with a volunteer army, you have more qualified people than if you

drafted them. Take me, for instance, I was a farmer. And a young one, too - I was just 17 when my Dad died. The six of us

boys were all in the service - I had two brothers in England; one brother was married and didn't go for awhile, but then he

went into the Navy; one brother was in the Air Force; and two of us were in the Army. That's the way it was.

How old were you when you went overseas?

When I went overseas, I was 18. I went over in about 1941 and a half. A hog bit my dad, and he lived one month after

that hog bit him. We had 365 acres here on the Rivanna River. When he passed away, my brother was married. My mother and

I went to Palmyra to get the papers stitched up so she could go ahead and keep the farm. But the lawyer wouldn't let her do

that. He said, "You have to start all over." I didn't know anything about nothing. I had finished the second year of high

school, and that's as far as I ever got.

Would you explain - your mother couldn't keep the farm. Why couldn't that happen?

He just said that she would have to start all over. But now, I ask myself, why would she have to do that? She and her

husband bought it together. And if something happened to him, why couldn't she keep it if she kept on paying for it. But

I didn't know anything about business - nothing. We asked my grandfather about helping us, but he didn't want any part of

it for some reason. So we lost it. One lawyer, who got to be the administrator, took the crops, the cattle, the machinery,

and everything. This other lawyer - we bought the farm through the Federal Bank Baltimore - took the place. My mother

didn't have anything but what was in the house. She had to move off the property. I didn't go back to school and I took

my kid brother, who was ten years younger than I was, and my mother and we went over to Boyd's Tavern on Rt. 250. The owner

had an interest in Phillip Morris Tobacco Co. at the time. He had 700 acres over there, and the three of us went in there.

I was trying to keep my mother and my kid brother. We planted wheat in October. The fertilizer came in 200 lb. Bags, and

the boss hollered, "Hurry up and get the fertilizer over here - it's going to rain." So I had three bags laying on the

ground, and I stooped over and picked up two of them, one at a time, and threw them up in the wagon. When I came up with

the third one, I tore both sides - a double hernia. This was Friday evening, and Monday I was in the hospital. I just told

my mama that I can't do this farming anymore. That was in the last of October. On January 1, I went in the Army. They

drafted me and then I had to find my mother a place to stay right quick.

Where did she stay?

Down next to Bremo - we got a place down there. My third oldest brother and my oldest brother bought it together, and

she had a place to live with my kid brother. That's part of my life. I grew up in a hurry.

I'll look for some of my papers and things. I lost my wife in 1992, and I've never gone through everything. I've

just not taken time to do that - it seems I always have something else to do. I want to bring my ribbons and some of

my papers that I had. I would love to have you see them. They're in my house somewhere. I have a whole string of

medals: sharpshooter, good conduct….I behaved myself while I was in the Army.

How do you get the sharpshooter medal?

Shooting a rifle. I could hit the bulls eye at 500 yards with that rifle. It was a great rifle! The MI….

Was that what you carried with you most all of the time when you were in combat?

We also had a little carbine, too, and we'd shoot that but it wouldn't shoot so far. But I

just loved the MI - I wished I could have brought one home.

When did you come home?

I was discharged in 1946. 3 ¾ yrs or something like that. See I didn't go in until right

after my father died and we got everything moved out of the house. This was in 1941 and in 1942 I went into the Army.

How did you stay in touch with your family while you were overseas?

I wrote them all, but it would take weeks and weeks and weeks for their letters to catch up with me.

What was the food like when you were overseas?

We were out in the field, and we didn't even have water to drink. We got water out of the mud holes. I

drank enough chlorine back in those days to last me a hundred years! You had to purify the water, and you

had a little canteen that would hold about a quart of water. They taught us that in basic training - they told

us that water purification was the difference between survival and dying.

All we had to eat were K rations in these little old cans - but it was enough nourishment to keep you going.

You didn't have much choice. And people didn't throw away food then like they do today. You go in a restaurant today,

and it makes you sick to see all the food they're throwing away.

Did you have any down time in between missions?

I can't remember much time off. After we came down out of Italy, that's when they transferred a whole bunch of

us off that ship there and put us on that hospital ship. They said they were going to take a load of our men home and

bring a load of prisoners of war back. So the rest of the time that I was in the service I was crossing back and forth

across the Atlantic…over and back…over and back. And every time we took Italian prisoners of war back, we had to repaint

that whole ship. All of the wards for the prisoners had to be repainted before they would put our men back into it. I

think I made 8 trips - it would take us 4 days and nights on the water to cross it. Then something happened on the ship

one time, and it started leaking water. I can't remember whether we left that ship in New York or over in Italy. But

they got everything off that ship and put it all on another one. So when we finished hauling those prisoners back and

forth and we had some really pitiful boys. When we were unloading at New York, we were trying to get these boys off the

ship, and I can remember this one man who came down the gangplank, and he was doing fine. When he walked out right on

the edge of the gangplank, he jumped over and down into the water. Other ships were going back and forth and crushed

him right up against the pier. We couldn't even think about getting him out.

|

| PFC Raymond Grandstaff was a member of the

201st Hospital Ship Complement, USAHS Algonquin. The Algonquin is shown above steaming out of port during WWII; it was home-

based in Charleston, SC. The Algonquin had a 400+ hospital bed capacity and made its first mercy voyage to pick up wounded

U.S. soldiers in North Africa and Italy in January 1944. (Photo from the Raymond A. Grandstaff Collection) |

Did he fall or did he jump?

No, he jumped! Some of the soldiers had both legs off, or one leg off, or an arm. But they did not want you to feel

sorry for them. I had a lot of experience in there, and I worked in that place. I finally got enough of that, and I

asked to be transferred down to the laundry. So we went down to the bottom of that ship, and it was so hot down there

that you couldn't work there longer than 15 minutes. That's where I finished up until we broke up the ship in New York.

We stayed in Staten Island, New York, for three days and then shipped out on the train and went to New Orleans. My wife

was in the service, too. I left her when I went overseas, and she was in Charleston, South Carolina. When I got down

there, the first thing I saw when I got off the train in New Orleans was her! I didn't have any idea she would be there

because I hadn't heard from her in a month. And she wrote me a letter every day. We moved so much that the mail couldn't

catch up with us.

|

| PFC Raymond Grandstaff was a member of the

Late in WWII, Raymond Grandstaff was transferred to the USAHS Algonquin, which transported wounded American soldiers

from Europe to the U.S. On its return trip, the ship returned POWs to Europe. Raymond made 8 trips on the

Algonquin which took 4 days and nights per trip. (Mobile Press Register; Mobile, AL, February 1944) |

So was she in Charleston the whole time?

No, she took her basic training in Iowa. Then they moved her from here to there - she was stationed at a hospital

for most of the war here in the U.S. We got married in New Orleans.

So that was after the war that you got married?

Yes, because we were in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean when Japan surrendered. They were heading us to the Pacific

then. We were so excited that we threw everything they could get their hands on overboard. There wasn't a whole lot of

stuff left around on that ship. Don't know why that was the only way we could celebrate, but it was.

It doesn't sound like you had a lot of leave time, right?

I didn't get any. The only leave that I got the whole time I was in there was when we finished our basic training in

Texas. It took us three days to get home on the train and three days to get back, and I had to be back in a week. I left

home on Christmas Eve so I'd get back to Texas in time to leave with my outfit. I was home a day and a half. The rest of

the time, I was trying to get here and get back. I just never wanted to be late, and I still am that way. If I have to be

late, then something went wrong.

When your service ended, you were in New York and went to New Orleans. Your wife was there and you got married.

What did you do after that - did you and your wife move back to this area?

She went home - after we got married, they discharged her. I went with her to Ohio. Then I had to go back to New

Orleans. At that time, you didn't get out until you had enough points. I don't remember how the points work, but I

didn't have enough to get out. But they let her go. I went down there and they finally shut that base down right

outside New Orleans and moved us over to Lake Pontchartrain. That's where the Air Force Base was, and that's where I

stayed until I got discharged.

When were you discharged?

I sat there with a one-star general and he said, "I'd like to have you reenlist." And I said, "Really? I think I've

had enough." And he said, "Well, we'll do this and we'll do that if you reenlist." And I said, "I thought I was going

to get my discharge today." And the general said, "Well, we certainly would like to have you back to stay." And I

said, "I think I've had enough, Sir." And I practically snatched my papers out of his hand and got out of there right

quick then. I said, "I'm going home!"

What were they offering you to stay?

I told you that everybody lost their rank and I was a PFC. Then he offered me a sergeant - three stripes if I stayed.

I still wasn't really out because I still had to come back to Ft. Meade, MD, where I was inducted into the Army. And it

took me another two weeks trying to get out of the service. And that's where I got my discharge - at Ft. Meade.

My wife was in Ohio, and then I went home to see my Mom and spent a couple of weeks with her. Then I borrowed my

brother's car and went to Ohio and got her (my wife).

Where did you live then?

We lived in Virginia. We went back and stayed one winter in Ohio, but it was so cold out there in the wintertime

that I said to her, "Come on, let's move to Virginia." So she came with me.

How did you meet her?

It's quite interesting how I met her. I met her in Charleston, SC. We'd run out of coffee, and the Sergeant said,

"Run next door and see if they don't have some coffee." So I jumped up and ran over there, and there she was. I asked

her, "Lady, do you have some coffee?" And she said, "Oh, I think so! Let me check." She went into the kitchen and when

she came back, she had a whole pot of coffee. She told me who she was, and I said "Well, that's nice. If I'm free

tomorrow night, I'll come over to see you." And she said, "Well, we'll meet in the day room." And I said, "Fine!"

And that's the way we got together - over a pot of coffee. There were just six in my family but there were 12 in her

family. Two boys, two girls, two boys, two girls, two boys, two girls --- just like that.

Then she had heart problems, and I lost her in 1992. We had three children. My son was in the service, but not

out of the United States. And I have 5 grandchildren. One grandson works here in the fire department.

Did you keep in touch with any of the soldiers?

I tried to - I kept in touch with one boy who was from Missouri and was a real, real Christian boy. He was just nice

and everything was so hard with him in there. I went to church, too, because my Dad took us. He was the Sunday

school superintendent, and if he spoke to you once, he wouldn't speak to you again about it. You take six boys, I'm

telling you --rowdy as they come!

Tell me more about how you lost your sergeant's rank and became a PFC…

Well, the Air Force blew the house up. We lost everything - we hardly had ammunition to last another thirty

minutes --- nothing. If they hadn't called the air force in, I expect they would have killed every one of us

because they were dug in. That house sat right up above us. They had all of the down shots at us and we didn't

have a chance. If you stuck your head up, they'd blow it off. That was the worst one that I ever got into.

But we got through it all right. Thank God!

So after you got your wife from Ohio and you moved to Virginia, were you a farmer then?

When I first got back, we didn't have a farm because it was gone. So I went to work in a garage in Columbia.

The Kent Brothers - they owned everything around there. And this one Kent boy had a garage there. Mr. Hollins

bought pulpwood and had a store right along the railroad tracks. I lived up at Fork Union, and my brother and

I went to work. He said, "You come on-I'll drill up the motor and you fit the rings to it." So that's the way

he and I got to do it. We worked in a garage. That brother and the next oldest brother were on an LST in the

Pacific. They farmed together, and I worked for the Uniroyal Tire Company after I quit the garage. And I worked

for them for 39 ½ years before I retired. And I've loafed ever since 1987.

Did you join any veterans' organizations like the VFW?

I belong to the Veterans of Foreign Wars right down here.

Do you go to any activities there or go to reunions?

Well, we enter parades and we've had the Memorial Day service. We have a lot of dinners with 100 people or more

to eat. That helps keep the post going and pay the bills. I used to stay pretty active, but I've got where now that

I spend so much of my time in the hospital. I have to have another operation on the 10th, and I've been down there

twice this week. I went there on Wednesday and on Friday, too. I go to the Veterans' Hospital in Richmond.

|

| Raymond Grandstaff's WWII decorations

(Raymond Grandstaff Collection) |

How did your service in the war affect your life -- you talked a little bit about not liking to go to the beach?

So many men got killed that the blood just ran and turned the water red. So I don't like water very much - would you

like the water very much after something like that?