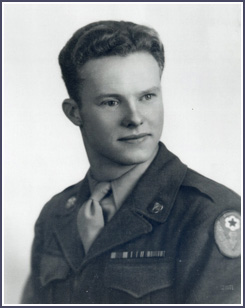

Oral Historian: Robert R. HunterInterview Date: 7 July 2008Interviewer: John McQuarrieI just have a couple of preliminary questions, for the record. What is your date of birth, sir?12/6/24 In what war, and in what branch of the service did you serve?Army. During WWII, correct?Right, WWII. Sorry, I'm a little hard of hearing. Okay. What was your rank when you were discharged?Corporal. Where did you serve?I served in, of course, the U.S., and also the European Theater of Operation-ETO-the European Theater of Operation. And where in Europe did you serve, sir?In France. What year did you join the service?July 15th, 1943. How did you come to be in service?I was drafted. When I turned eighteen I was still in high school and I got drafted, but I got a six-month deferral to wait until I finished school. Had you thought about going into the service before that?I figured I'd go. Yeah, I had thought about it. Everybody else was going, and I knew I was going too. My brother left before I did. But you know, when I heard about the bombing of Pearl Harbor, I was sixteen. I remember that my father was in WWI, and I said, "You have to be twenty-one to enter the service." It didn't take long before they dropped that age to eighteen. So I just made up my mind that I'm going to go; I'll be all right. But he was gassed in WWI and died in 1930 of lung problems, I guess. I'm sure that kind of played some part in your feelings about serving.How's that? I'm sure that impacted how you felt about going into the military.Oh yeah. I thought about it. He took me to a movie once when I was five years old. I thought about it. I was hoping I'd never have to go, but anyway, things change. I had no objections whatsoever, though, about going in. In fact, I questioned whether or not they would take me, as I had lost an eye when I was eighteen months old. So, when I went in, I said, "Well, I'll at least go in, but they'll probably put me on limited service." Which they did. Well, you train for an MP or a medic, but you don't expect to be a combatant. But I fought that issue, when I first went out to Ft. Custer, MI, because they put me into a casualty company. They had a lot of guys in there with problems, you know, health problems. So finally, after six weeks, they selected me to become a military policeman. They looked at me-six feet, one inch-they took tall individuals, so I was selected and trained as a military policeman until 1944, when they were looking for medics. So they sent me out to Ft. Lewis, WA, to train all over again to be a medic. I finally ended up as what they call a surgical technician. They assigned me to a General Hospital. That's when we went overseas…with the General Hospital. And you were in the 300th…?The 306th General Hospital. Can we back track a little bit, and tell me, physically, how your transition was from being a civilian, eighteen years old?As far as I was concerned, it was a great life. I enjoyed the hell out of it. So you went from Richmond to Ft. Custer?

So you said that you pretty much enjoyed your time training, correct?Yup. What did they have you doing? You said you went from being an MP to a surgical technician, but how was your basic training experience?

What was that like?That was interesting. I'm sure it was. Did they know that you were training to be military policemen?They were very cooperative in every respect. I think they respected the American troops. In fact-I'm going ahead a little bit-I had ten German prisoners that I worked at a lumber camp, down in the woods someplace, a mile and a half away from anybody. Ten of them, and all I had was a little carbine. I couldn't pronounce their names. We'd go out there everyday-they'd march; they were stacking wood, lumber. This guy, one of the Germans, taught me how to count. He said, "I want you to…we'll line up, and you count: eins, zwei, drei, vier, fünf, sechs, sieben, acht, neun, zehn." So that's the way I remembered it. But they were superb people. It was very interesting to see that, to work with them. It really was. That's really cool.I enjoyed that. That's an interesting experience, I'm sure. You hear all this propaganda about the Germans, and then to actually meet them…They were very athletic. We used to have to search them-when they'd come in-we'd have to search, and they were very cooperative. No problems, none of them gave us any problems at all. Except for when I was a medic-I'm going a little ahead now. When I got back to the states, I was in Ft. Monroe Hospital, and one German, one of the patients in the hospital, he got up one night and stood up in the hallway and wouldn't move. I couldn't move him. He would lean up against the wall all night long. He was just rebellious. I finally clipped him behind the legs and picked him up and carried him and put him back it bed. But all night long, he stood up. That was the only real problem I was concerned about. Right. Okay, so, after your training at Ft. Custer, as an MP…After Ft. Custer, we went to a place called Ft. Jackson, MI, for about a week. I think that was just to get experience in transporting a company. From there, we moved to Ft. Wadsworth, in New York, Staten Island, again as an MP. And there, we…our purpose was to go down through the ships that came in, they brought prisoners from overseas, and we'd pick them up off the ship and put them on a train. We would transport them to Lincoln, NE, Tennessee-different places. One of the most interesting trips we had, we had forty Nazi prisoners-high-ranking German prisoners-and I was selected to be on the six-man crew to take them to Ft. Knox, KY. They were very well behaved…no problem whatsoever. But six of us took them down there. Anytime we went from New York through Detroit and Pittsburg, all those places, the shades of the train were up. We wanted to make sure they saw what was going on through those steel-mill towns, you know? They were just amazed. You could tell that they were so fascinated with the country itself. Were you instructed to do that, or did you just decide to?Well, no, that was a procedure. Keep the shades up on the train. They couldn't pull the shades down. Part of psychological intimidation? That kind of thing?Yeah, that's a good phrase; it was psychological. A lot of these Germans came back to this country after the war. Back when I was working in Richmond, there was an engineering firm; we had a guy that was in the Luftwaffe, and he came to us looking for a job. We had a Jewish architect there, an elderly gentleman, and we couldn't hire the guy because we didn't want any problems, you know? That's the kind of thing that you visualize could occur. Okay, so…?After Ft. Wadsworth, let's see… That's handy that you have all those papers.Let's see. Oh, Ft. Custer…after Wadsworth, we went to Boston. Oh, okay. So that was before Ft. Wadsworth?No, that was, I'm sorry, that was after Ft. Wadsworth. In March of '44 we went to Boston. There, it was a different experience, and we had Italian prisoners. We were in South Boston, and we had a compound that was right in the city, practically. It was in the city. We had more trouble with the Italian-Americans coming over and throwing stuff over the fence to the prisoners, because they all had ancestors. Boston was an Italian town. I had ten…I had ten Italians we'd pick up every morning. They would come from the port of embarkation in a truck, and pick me up with my ten prisoners, and take me to the port of embarkation to work on the railroads. There, they had huge buildings with thousands of women working in them. I'd take up in a little shack and sit down in the shack, and we'd talk with them as best we could. The women would drop notes out of the windows for the prisoners to pick up. Because they were free to roam around in a certain area, you know? But anyway, that was an interesting thing, and I thoroughly enjoyed that. There was one guy who was about 6'4", and he was a prizefighter in Italy. His name was Joe-he told me his name was Joe-and he called me 'Bob.' You get to know these people. They're just like humans; they're friendly, entertaining. One of them picked up my rifle one day and handed it to me. I had to get up and go. My carbine was leaning against a wall and he picked it up and handed it to me. So that's the kind of people you're dealing with. Very cooperative, very friendly. We left Boston on 4/16/44. We went to Cape Cod, Massachusetts. There we were…then we were converted into what they called a service unit. We had a compound of German prisoners that we were guarding. I think there was about four or five hundred of them. Each one of us had a certain number of prisoners that we would take-they'd work in the mess hall, and work here and there-each one had a group. Then, in September '44, they disbanded us and sent me to Ft. Lewis where I took my medical training. The field training and all that: there were a lot of lectures by doctors and surgeons and all, on how to care for… They'd take us out and simulate wounds of soldiers and show us how to treat patients, and that sort of thing. I think we stayed in Ft. Lewis…well anyway, I know we left Ft. Lewis after training, which had been about nine weeks. Were you at all disappointed to have been transferred out of the MP unit?In a way, because you're leaving all your buddies. It's a whole new ballgame. And I was disappointed, but I could see the need because they were preparing for a tremendous amount of casualties in Europe and Japan, so they were planning ahead. They knew what they were doing, because… If this was September 1944…then yeah.From there, they sent us to…let's see… Had you ever had any prior experience with treating patients, or first aid?Well, you mean wounded soldiers? No. What we did was, when we went to Ft. Lewis, we went to Ft. Jackson, which was a training command for General Hospital work, and then we went overseas in March '45. There we took care of the emaciated prisoners of was-the American prisoners of war. That was the extent of the attending the wounded. I didn't really get into that. So no combat injuries…No combat injuries: they were already emaciated. We took care of them until we could provide transportation back home. After that, a whole lot happened over there. I met one of my cousins over there for the first time. He was an MP. I met him over there for the first time. And then we went to what they called Camp Victorette, in Marseille. This is while you were still in France?Yeah. Where were you first stationed in France?

Oh yeah?Yeah, they threw it overboard. Somebody found a case of whiskey on board. I don't know where they got that. Of course, I was too young to drink, but anyway, they celebrated. Then we…they brought us back, we came into Boston, and from Boston, they sent a bunch of us to Camp Miles Standish in Massachusetts, which was sort of a disbanding group. They would let people, who had enough points, get out of the service. Well I didn't have enough points to get out of the service, so they sent me to Camp Sibert, Alabama. I'll give you a print of this, so you can follow the dates and so forth. From there, they sent me to Ft. Monroe. At Ft. Monroe, I was still dealing with prisoners, for some reason or another. They called my up one day-this was in April, March or April-they wanted to know if I could take six German prisoners to Ft. Lee. They were mental cases. They said, come over and get an ambulance, and we want to you truck them to Ft. Lee. Well I didn't even have a driver's license. They guy checked me out on an ambulance, and put these six German prisoners in the back of the ambulance, and I had to drive them all the way to Ft. Lee by myself. How the hell I got there, I don't know. Was that one of the first times you'd driven a car?Yeah! They had to teach me to shift the gears in the damn thing. Anyway, that worked out, because I got back all right. In April, toward the end of April, they discharged me. I got out of there, so that was about the end of my career, except I re-enlisted in the reserves, which wasn't a smart thing to do. I re-enlisted-I was at Virginia Tech-and 1949, I said, "things don't look too good, I better get out of this. I'm about to graduate, I don't want to get caught back up in the Army again." So that's when I got out, I resigned, and they gave this to me. I can copy all this stuff if you want. But I thought that was the next step, to go ahead and continue, to get an education under the GI Bill, which was the best thing the government's ever done. We had about 1,500 veterans at Virginia Tech in 1946. Wow.The 306th General Hospital, actually continued on in the 50s, and finally disbanded in 1959. After Korea?What happened was, I went on the computer and asked if anyone had been in the 306th General, and I got a reply. The guy sent me a whole bunch of stuff. It was the same outfit, but everybody was different. I never knew that until I got on the computer. Because I always wondered what happened to all those guy you serve with. This, this right here, you can get a print of that. You can get a lot of information about some of the activities. MRS. HUNTER: How are you all doing? Very well, thank you.MRS. HUNTER: Did he tell you that he won the war single-handedly?Not yet, we're getting to that part.This is the historical data on when I was a military policeman. This comes form what they call 'the morning reports.' That's how it ties in these dates. Right, that's very helpful.You can go back and realign some of these dates if you have to. I had a couple questions about your impressions of your service before we move on to a different category. It seems like as a military policeman, and as a surgical technician, you worked with POWs both times, is that correct?Mm-hmm. What were your impressions about the difference in treatment between German prisoners of war and American prisoners of war?They were both appreciative; whatever you did them, they appreciated it. I didn't see any animosity at all, or anything like that. They were very appreciative. How about in terms of the captors treatment of the American prisoners? You said that a lot of the prisoners you treated as a surgical technician were kind of in bad shape.Yeah, they were emaciated. I don't know, they were just thankful that you were there to help them. Right. Did they seem to have any resentment toward the…?Oh no. No. We had German prisoners right there at the camp with the American prisoners of war. We had a camp of Germans-of course, I wasn't involved with the German prisoners then-but there was a whole camp of German prisoners doing menial work at the campsite. We had thousands of emaciated prisoners in tents, trying to get them set up so they could come home. There was never any real animosity. They would roam through the camp. Really?Yeah, it was just sort of unbelievable. It was all over. That's interesting, and I wouldn't have thought that that would have been your answer. My impression would have been that the American soldiers would have been…I didn't see any of that. I guess they were all sort of just relieved, you know? So when you were treating these gentlemen, the war was completely over?Yeah, the war was over then. Even though the war was still going on when we had work details. Oh yeah, when we had them, when we would transport them all around the country, the war was still going on. It was going on heavy. Again, I didn't see any real, anything to be alarmed about. I think they were happy to be out of the war. They were, they were happy to be out of it. Was it just kind of an understanding? That prisoners of wars - that was just part of combat and things like that? People are captured…Yeah. I had friends who were, never got overseas, because they were torpedoed on ships. There was some resentment, to a certain extent, but you got on to something else. You couldn't dwell on that. There was one boy who I was raised with who was going overseas, and the Germans torpedoed the troop ship, and they lost thousands of them. You can imagine. He was one of them who was training in Florida. He and Clark Gable trained together. He sent me a picture of him, but Clark Gabble wasn't on his ship with him; he was Air Force. But anyway, a lot of interesting things happened, that sometimes I can recall, but once I go through this stuff, I can finally figure out some of the things going on here and put it all together. What can you tell me about your day-to-day life as a soldier? You had the opportunity to experience life as a soldier in the United States, and then, obviously, in the European Theater. What did you do on a daily basis?Well you would…the normal Army routine. You'd get up in the morning, do your duty, enjoy yourself whenever you could. Just relax, shoot pool: it was normal everyday living. It was a whole new life, but everybody seemed to understand that and get along. There was no real problem. I didn't see any problem at all. I enjoyed it; I enjoyed every minute. And how was the food and the accommodations?Sometimes good, sometimes bad…it wasn't ever really that bad. In some of the letters I was reading that I wrote home and said the food was good. We had three good meals a day. I thought it was good…well prepared. So from your point of view, you were well supplied and being taken care of?Oh yeah…well supplied…plenty of food. Now the Germans, when they used to get their rations-meat, potatoes, vegetables, what-have-you-they had one of those huge twenty-three-gallon refuse cans, all of it goes in there. They had a fire; they put it on a fire, and cooked every damn bit of it into a stew. They made a stew out of everything. It simplified their mess problems. They all had their little tin cups, and they'd come by and get a cupful of stew. I notice when we were taking those Nazi prisoners down to Ft. Knox, they would come through, and they had a big tub. Two people would have a handle, and they'd be dishing out the supplies to them. That's how they did it, which was a smart thing to do. We didn't do that; we had our separate mess kits…separate everything…separate compartments. Did they feed you about the same?Yeah, same rations…they had the same rations we had. One of the things: the prisoners who were emaciated, they didn't have those kind of rations. That was the one thing, if there was any resentment, it would be that fact, that they didn't have anything to eat and we were feeding the German prisoners good rations. So you were feeding the German POWs what you we eating yourself, both in the United States and in the Europe.Well I didn't have much to do with the prisoners in Europe. I was on a station that had prisoner. That was in France. What was the reasoning for not feeding the American soldiers as you were feeding the German POWs?Well that wasn't the American system. It was just like a meal at home. But the Germans, I guess, lived in the fields, and that's the way they'd eat. It's the way they fixed their meals. That's interesting.It made sense to me for them to do that, because they didn't have to make preparations for each individual food. Meat, potatoes, whatever… Oh, so you gave them the same rations and they cooked it themselves.They had the same rations that we had, and they cooked it to suit their needs. Funny story though, when the war was over, we had this tent city of all the prisoners. I was lying down on one of these cots, and this nurse was sitting there talking, and a whole flight of B-17s came flying over, real low. I said, "Boy, that sure is nice." And she said, "Aren't you glad you're going home?" And I said, "I'm not going home, I'm your ward boy." That was fun. But anyway, we used to wake those guys up in the morning for breakfast [the emaciated, American POWs]-they had six meals a day-and one of those guys I used to wake up, he used to wake up and crawl under the bunk because he was so nervous. He finally got over that. One guy asked me to mail a letter for him. It was almost next door to my mother in Richmond. His name was Cole, and we got to talking; his mother almost knew my mother, they were so close. After the war, I ran into this guy again. He was working as a maintenance man. I knew him right off the bat. He was working in a boiler plant. You brought me back to thinking about a lot of little details that happened in the past. That's good. That's excellent.I was really and truly looking forward to the experience of traveling. When we were going, I thought we might go all the way as far as the South Pacific, and I was really let down, as far as my military career was concerned. I was disappointed in that we didn't really get to that part of the world. Traveling was a big thing for kids back then; you get to see sights you've never seen before. I imagine that would be interesting for you; you said that your induction was the first time you'd left Virginia.Yeah, I'd never been more than fifty or sixty miles from home. You see, I was raised in a Masonic Home, which is not an orphanage, but-in Richmond. You may have heard of it, but you may have not. It no longer exists. They have a retirement center there now. I was raised with about 265 other kids who didn't have fathers. We all were like brothers and sisters, really. So to get away from home and travel, that was a big thing. Do you think that made it easier for you? Less homesick in a way, to go and join the service?Homesick? You know, no, not at all, and I've often thought about it. I said, "I'm so glad." I felt bad for a lot of the kids my age because I'd been taking showers in groups; I'd been undressing in the dormitories with groups. I said, "These poor guys. I know they have it bad. They must be embarrassed, or not embarrassed, but intimidated or whatever." I know they had a hard time with group activities: dressing, undressing, going to bed. It didn't bother me at all. I felt that we grew up with it. They had been in homes-private homes-where you didn't associate and you didn't have to worry about that sort of thing. But that was one thing that didn't bother me in the least. So it kind of made it easier for you?Oh it was very easy for me. I was used to being around groups-large groups. We had one hundred boys, one hundred girls, always around doing something, and we didn't mind taking orders, because we were always taking orders. There was always someone over you. See, we didn't have a family life like these other kids in the service, and I was able to adapt to the service because I had already sort of been used to it. It sounds like you really enjoyed everything you did over there.I thoroughly enjoyed it. I was going to ask you what you did for entertainment, when you weren't working or anything.Movies, football, baseball, intramural type stuff. There was one thing, when I was in France, we had an entertainer to come over called the Ortega's All-Girl Orchestra. Well I was sitting in the back, sitting on the top-I've got a picture of it somewhere-in the back row. You could barely see them, but a friend of mine, went down after the show, and he knew one of the girls in the band. We went down backstage and got to talking to them, because they were friends. Now what happened is, they were playing at another place the following week. He said, "We'll come over at watch you-see you." He wanted to see her because they were school buddies together. This girl played the saxophone. Pretty girl. We hitchhiked a ride over there. Hitchhiked-an ambulance picked us up. He said, "You can ride in the back if you want to; you sit in the front." So I got in the back and there were two dead Germans back in the back, wrapped up in a blanket. They were rolling back and forth. We took them to the cemetery because the guy wanted some help. The guy driving the ambulance wanted some help, so we helped him take them out at the cemetery where they were burying the Germans. Anyway, we finally got to this place where the girls were going to play, and it happened to be an officer's club. They ran us away; they wouldn't let us see them. They said, "You're enlisted men, you've got to leave." We had to hitchhike back to camp. Well, years later, when I was at Ft. Monroe, I was at the movie picture show sitting up in the balcony. I had a date. When you walk in, you can see faces. We couldn't hardly see them, but they could see us. They came over-the girl came over-across the aisle and said, "Hello, how you been?" She recognized me. So I said, "Where are you playing?" She said, "Oh, over at the Monticello Hotel, in Norfolk." I went over there the next weekend, and I took her to the dance floor upstairs. It was a strange thing when you meet people over there, and then years later you run into them just like that. Anyway, there's some of the interesting things that occurred. Other than that, do you have any particularly funny anecdotes or anything like that that you can recall?Any what? Any funny stories, either from your time in America or over in Europe?The Stage Door Canteen over in New York. I don't know if that's particularly funny, but it's one place that I always wanted to go because I'd heard about it before I went into the service. When I got to New York…a friend of mine-he was in New York-we used to sit at the same table together when we were at the home. I remember one morning, he ate pancakes, and I'd never seen so much syrup on them in my life. Well, the first thing you do when you go for a physical is you have to give a sample-a urine sample. The guy was lined up at the door, and [another] guy said-the sergeant said, "The first thing we want you to do is give a sample in the bottles over on the table." One guy said, "From here?" Anyway, the friend of mine had sugar on his kidneys, and they put him 4-F. The guy was quite an entertainer in his own rite, in high school. So he went to New York, and we men. He called me because he knew I was there. He took me backstage to one of the stage show, and we met Allen Jones, he was a singer, and he knew his way around the stages in New York because he wanted to try to become an actor. We got-one of the entertaining things-we got to meet Allen Jones. He knew him because he had been backstage trying to get set up in the theater, himself. It's interesting, he finally got in the service, himself. But I thought that incident…it stuck with me. When you go in for a physical, you run around all naked. The Belgiums over in Richmond. Do you know where that is? Over by the Union Cemetery? The Belgiums was used in the New York World's Fair as a building, and they gave it to Richmond. And they hauled it down there piece by piece and rebuilt it. That's where we were inducted. I thought that was something else. Tell me about your trip from the States to Europe. What were your first impressions about leaving this continent and traveling across the ocean?That was an interesting trip. I was supposed to have been the best man at my brother's wedding, and I was on the train, getting ready to unload on the ship. He was getting married back in Richmond. We got on the ship at night, and we had 50-some nurses with us, and about 3000 men. The first four days out at sea, I was excited. I stayed on the fantail and watched New York Harbor disappear. Really interesting. We ran into a storm in the North Atlantic. Everybody got so damn sick I didn't think we'd ever make it. Anyway, they had a little harassment with the nurses trying to come down to the mess hall through these 3000 men lining up. So they selected me, for some reason or another, to go up on the top deck and guard the nurses. I guess it was because I had the military police training; I don't know. I used to get up on the top deck. You couldn't believe it-the sun shinning. We'd play cards all day long, you know, and they were really nice…really friendly, and when the nurses went down later on, everybody was standing up to make a path, and they all held their hands over their head. You could see them all marching. I thought that was funny. Going down to mess hall, in the hold, you'd go down a staircase into the ship, and the ship was rocking and rocking. You'd get to these long tables, and you had your mess kit in front of you. The ship would roll this way, and your mess kit would fall down. Then it would come back the other way. That was an interesting trip. But the whole time, I got to thinking: something's going to hit this ship before long, because I kept thinking about my buddy. I slept with my boots on. We got to Le Havre, and you could look out and see smokestacks sticking up out of the water, and some explosion went off somewhere. I don't know what the hell they were dynamiting over there, but that scared the hell out of me. I bet so.Well you see all these ships damaged during the war. That was an interesting experience. When we got there, they put us on these huge trucks and hauled us through Marseille and all through the city, and way out where there hospital was set up. That was quite a transition. How long did it take you to sail across?I think it took us a little over seven days. Seven or eight days-we were really moving. Could have taken ten days, I don't remember. What time of year were you sailing?March. Oh, that's not bad.No, but there was that terrible storm in the North Atlantic. Let's see, move from the European Theater of Operation to the South Pacific…departed Ft. Jackson, South Carolina…arrived Camp Kilmer, New Jersey…Brooklyn, New York. We had an advanced group go overseas before us...arrival: we arrived in France 4/4/45, and we left March 23rd. So 3/23 to 4/4?We were on the John Ericsson, and arrived in France 12 April. I think they set the arrival…oh, that was the advanced party. We got there 4/12/45. I'll give you a print of this and you can follow everything down. How was your trip back?The trip back was sort of, uh-I didn't get seasick. I remember looking forward to going to the Panama Canal, but we didn't get to go the Panama Canal. After the war, a friend of mine said he was down there six, seven, or eight weeks in the hot sun-he left before me. It was a good thing we didn't go down there, because the ships were backed up going through the Canal. Anyway, it was a nice trip. I got up on the forward…I stayed up on the deck most of the time, and I couldn't believe that this was happening. I was eighteen, or nineteen, or twenty years old, and here I am in the middle of the ocean, and going home. It was a great feeling. What was the first thing you did when you got off the ship?I remember we got on a troop train. They put us on a troop train. One of the MPs who was guiding us through was an old…I met him before I went overseas, so we had to chat a while. We went to-that's when we went to Camp Kilmer, I think. Anyway, another interesting thing: when I was in New York, at a USO, I was standing in line with a friend of mine, and we were talking, going up a flight of steps of this USO building. He was on the Normandy, the USS Normandy, the largest ship afloat. It caught on fire and capsized in the harbor. In New York Harbor?In New York Harbor. He was due to be on that ship, but he was on leave in New York. So we were talking about it-his name was White - we went upstairs, and that was the last time I saw him. The next time I saw him, we crossed each other at a transportation center in Marseille. I said, "Hey White, how are you doing?" This guy had been overseas - he finally got overseas-and I caught up with him. I thought that was weird. These things pop back in my mind every now and again.

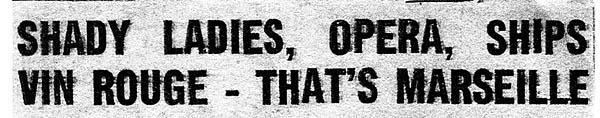

Oh, wow. Oh, this is what you were talking about; this is the staging area. What's this circled part there?I think that's…I don't know why I did that. It must have been-I don't know. This could have been tents instead of vehicles. They were back on another area, closer to Marseille. Anyway, that's where all the staging area was, but I know the vehicles-the armored vehicles-were all close to Marseille. We had to go over a mountain to get to Marseille…a hill. But this is the thing I cut out of the newspaper describing the city. It tells it like it was...

We were down in Marseille in one of these off-limits places, and a couple of us went into this bar. It was a terrible looking place. There was this guy behind the counter, and he had on a GI undershirt-a khaki undershirt. He was black, and he was speaking to us in broken English, as if he was…he was AWOL, as we found out, but he was speaking to us in broken English. He said, "Here comes the MPs." So he put us in the women's toilet. The MPs came in, checked: nobody there. I came out and said, "What are they looking for?" He said, "Oh they checkin' passes." He went back to his African-American lingo. "Oh they checkin' passes." Up until then, he was a Frenchman. "Oh they checkin' passes." So why were these places off-limits in Marseille? Just to keep you out of trouble?Yeah, oh yeah. It was heavily armored with military policemen. There were a lot of people getting in trouble. They were there to look out after us. But a lot of times, you didn't know whether you were off-limits or not, because you just wander down the street, go in an alley. The place had; there's no tourists. In fact, I was over there on Bastille Day: the French Revolution. It's coming up soon-next Monday.That's right. They had a contest out in the harbor. I had a picture here that I can't find. They were jousting on these boats. These boats would come at each other and you'd have to knock him off with these long spears. That was their contest. It sounds like Marseille made quite an impression on you.Yeah, yeah it did. It did indeed. That was the scum of the earth. It really was. Was that your favorite part of the service?Not really the favorite, but it was the most exciting. It was: everything was happening in Marseille. Not very much like Richmond…No, but of course, Marseille, I understand now, is rebuilt. The Germans destroyed the whole waterfront, and now it's all rebuilt. That was about the worst place I went. Is that right? Wow.I can't find that…it makes me mad because I just looked at that thing upstairs. We can come back to it.These are some letters from Owen Pickett, who wrote me…this was one of the responses from Own Pickett to one of my requests. So you were also-and this is just for my records-you were in the 500th Military Police Escort Guard Company. Is that what that says?Yeah. He put all this stuff together for me. He really wanted your vote, huh?Yeah. He was a fine guy. He was a year behind me at Virginia Tech, so we had a little something going. That was the next set of questions I was going to ask you about. When you got back, and you we discharged, how was your transition out of the service?It was a little different. I really didn't have a place to live, because I had left the home. I had no place to live. My mother had a little one-bedroom place where she lived. She was a practical nurse. She found me some friends in the neighborhood. I'd spend the night at one house, with one family, spend the night in the next one. Finally she found somebody who was a member of some lodge or something, and I was able to stay there until I went to Virginia Tech. It was tough; I didn't have a place to stay. It was a huge let down; believe me. I said to myself, "I could have stayed in the service and had three meals a day and a place to sleep." Well that's what you were saying. You had kind of prepared yourself that you were going to have to serve when you turned eighteen, and decided that that was going to happen so you didn't make any plans.When you were at the home, you had to leave anyway. When you were eighteen, you left, and you were prepared as best they could to meet the world. You either went to college-they would send you to college, but I don't think my grades were high enough to go to college. My brother went to Virginia Tech. They were sending everybody to VPI. I didn't have to worry about what I was going to do when I left there, because I was going in the service. You just knew that that was going to happen.I was going to get in there. In fact, they tried to weed me out several times. I had to go for a physical half a dozen times when I was in Ft. Custer in this casualty company. The guy would say, "Can you see anything?" I would say, "I can't see a thing." Then he would say, "Can you see anything?" And I would say, "I can see two fingers!" Then he would make you go…strip you down to nothing and go over every inch of your body. They'd finally find a way to send you away, like flat feet or something. They'd find a way to get rid of you, some legitimate reason. But they couldn't find anything wrong with me, no reason that I couldn't do something limited, on a limited basis. Why were they trying so hard to get people out?Well, I think they were looking for a certain caliber person. Some people would come in limping, with all kinds of complaints. They would go to sickbay; they couldn't put up with that kind of stuff. You were either healthy, wealthy…healthy or not. But I kept putting up a fight because I wanted to stay in the service. And they kept me, thank goodness. That's a far cry for how it is now. They keep lowering the bar everyday.That was…I lucked out there. Otherwise, I don't know where I would have been. How long after you moved…where was your mother living?She was on the North Side, on Lam Avenue. So, in Richmond?Yeah. She's dead now, though. She died a long time ago. Right. How long was it after you moved back that you decided to go to Virginia Tech?I got out in April, and I got a job working in May and June. I met a friend of my on the street, on Broad Street. His name was Tom Cox, and we played football together. He was quarterback and I played backfield, or something or other. We played football together in high school. He had a postcard, and he said, "Come on with me and to Virginia Tech." He said, "I've got a postcard here for you, an extra postcard. All you do is fill it out with your name and address and send it on in and say whether or not you want to register." A postcard. I signed the postcard, sent it in. They mailed me back and asked, "What do you want to take." I said, "mechanical engineering." I don't know why I said mechanical engineering. My father, he worked on cars. I said, "Okay, mechanical engineering." So I got accepted to the mechanical engineering department. So I went and bought me a trunk; bought me a lot old army uniforms and things, because they didn't have clothes-you couldn't buy clothes. That was the age when you couldn't even buy a white shit, because they didn't have them, so I kept all my army clothes. When I left, I took everything I had: a whole trunk full of stuff. They accepted me, and I went up to Blacksburg in September of '46. It was time to matriculate, and I got in the wrong line. I got in the electrical engineering line. After standing there for thirty minutes, I got up to the desk. They couldn't find my name or my postcard anywhere. They kept searching. I was like, "What the hell? What's happening?" Well, I told them what I'd filled out, and they said, "Oh, well you have to go over to this line." So I went over to the mechanical engineering line, and sure enough, there that card was. "You're accepted." Then they sent me to a barracks. They sent you to a barracks at Tech?Yeah, they sent us to an old army barracks over at Radford. They didn't have enough room over on campus. Jeez.So they sent me over to Radford; it was an old army munitions place. Right, Radford did a lot of that.So I had a room; the barracks was sent up into rooms, and my roommate and I went over there together for our first year at Rad-Tech. We called it Rad-Tech. The second year, we moved onto main campus. It sounds like your experience at Tech was a lot like your experience in the Army.It was great. I went to summer school because when I came home, I didn't have anywhere to stay. I worked for the highway department one summer and stayed with my friend at his house. I said, "I'm going back. I'm going to spend my summers up at Tech." I got a job working in the mess hall. I worked in the mess hall for two years, and that paid my…of course, the government paid for your tuition and room and board anyway…but they gave me back my room and board money because I worked. All of it was paid for, so they just gave it to me. I graduated in 1950. I wasn't the brightest guy; I finished about halfway-200 and something, 233. But it was tough on me. The first semester, I had to take three math courses because I didn't take solid geometry in high school. I had to take three math courses for two semesters. I don't know how the hell I made it. When I graduated, I had a job…I already had a job: $243 a month. Most of them were getting a $195 from Dupont, and places like that. I got married in March before I finished. So I had a job, and I guess because I was married, the boss gave me more money than these other guys were getting. That was pretty good money in those days. Then I became…I took the exam for a professional engineer, and I passed the state, two-day exam in 1950, to become what they call a certified professional engineer, which I was glad to get. I was one of the few at that time that got it. It was a two-day exam. From there, I was able to practice engineering. And that's what you've been doing since?You can always sign your name as a professional engineer. I retired as a professional engineer in 1987. I was the Acting Director for Engineering and Building, Division of General Services for the State of Virginia from 1980 to 1987. I was the acting director, but I went there as just an engineer. As I went through the years, after five years, my boss had a heart attack, and they put me in his position. He'd been there for thirty or thirty-five years. That did me in. They gave me the acting director. What happened was, I had a heart attach in '87, and had to quit. I was on what they called disability. And that was in '87. I retired in 1987 at 62; I was 62. I wasn't quite there for social security, but I took it anyway. I think I took it anyway, because I didn't have a pension. Because of the disability, I got a disability pension, which in turn, paid all of my GI Insurance premium. So every July 15th, they'd send me a check for $500-some. I called them and I said, "I'm retired, and I'm on disability." They said, "Fill out this form. You've got a pension." So I did, and they sent me back something saying it wall paid for; it had all been paid. That was a stroke of luck. Yeah, I'd say so.Then we moved to Virginia Beach, and that house down in Virginia Beach, we bought back in 1958. Two blocks from the ocean for $16,000-almost on the ocean. We lived there before I worked in Richmond, and then we retired and moved back to the Beach. We let somebody else pay for it; we rented it, you know. Then we bought this in 1978. And our kids…three of our sons lived here with their wives. Is that right?Yeah, I have four sons. They lived here, and then my oldest son-my third son-came in here and did all this work. He built the bookcases, put all this fancy stuff here in the hallways. He's a professional carpenter, and he loves trim work. He came in here, hired the panelists, hired the painters…hired everybody. He upgraded, put air-conditioning here, and did the whole thing. He did a terrific job.Yeah, he did a beautiful job. He built these. We like it here. It's nice and comfortable. Were there any final thoughts you'd like to leave me with about your service to kind of tie all of this together?I think it was one of the greatest experiences of my life. Everything that has come to be had been as a result of my experience in the service. I don't think I've ever had any regrets whatsoever of the service. I just enjoyed that thoroughly. I remember one time, going back to a little story from Ft. Custer, Michigan. We had 200 German prisoners that we were working in the laundry-in this huge laundry. All the windows were all lit up at night, and they would work them until midnight. Well our job was to take them up there, get them through work, and take them home. We had two hours of guard duty, and two hours off. Well, when you exchange rifles, go to port-you know-you had ammunition, which you kept in your belt. Well he didn't take the ammunition out of his gun. The poor corporal was standing right here, and he handed me his gun, and it went, POW! I almost blew his head off. All the German prisoners in there hit the deck. You could see them all through the windows as they all hit the deck. The poor guy, he caught hell. I bet. Yeah.They didn't do anything to me. I don't how in the hell they didn't do anything to me. I had my ammunition with me, and I said, "The damn gun was loaded." I remember matching him home. It was the quietest night you've ever seen in your life-snow on the ground. The commanding officer: he must have heard it, because everybody converged on it. There we were standing there, trying to explain what happened. We got their attention. Taking him home: the longest road, and the snow was thick on the bank. We had to walk along the side of the road, and we had a big searchlight that shined from up on top of the truck on the prisoners, and we walked along side them. The next thing that happened to me, I slipped on the damn snow and fell down the damn bank! Thing like that happened though. Nobody ever said anything to me about that. They'd talk about it, but nobody ever blamed me for the problem. I felt so bad for that guy. God, his name was Ward, and it seemed like everything always happened to…he was always getting in trouble. Everything always happened to him. Oh, he was THAT guy.He was one of those sad sacks, they called them. That was Ward. I don't know if they transferred him or what they did to him. I remember that he was there in Boston with us. I remember that, but I don know what happened to him. That was another thing that popped into my mind. When things happen to you… Alright, well, I'm going to stop the tape. Thank you very much for talking with me about this.It's been interesting. It's been interesting. I never thought that that this day…that something like this would happen. I really never did. I didn't think that my service was that important to go down in history.

|