|

Mrs. F.R. Moon Jr. Won't Forget Pearl Harbor;

She Was There In 1941 When Japs Attacked

The Daily Progress, Charlottesville, VA

December 7, 1953

Mrs. F. R. Moon, of Scottsville, won't forget Pearl Harbor as long as she lives. She was there when it happened.

Mrs. F. R. Moon, of Scottsville, won't forget Pearl Harbor as long as she lives. She was there when it happened.

A Honolulu resident for most of her life preceding the outbreak of World War II, when her Army father was stationed in the

Hawaiian Islands, Mrs. Moon was assistant dean of student personnel at the University of Hawaii when the sneak Japanese attack

on Pearl Harbor came. At that time, she recalls, she was living some miles away from the Navy installations under attack, so

she was not actually under enemy fire that Sunday morning 12 years ago today. But a shell landed adjacent to the church

she had attended that morning.

"We'd been living under tension for a long time. We were prepared and then again we weren't. Bomb shelters had

been dug and other preparations had been made," she recalls.

Had Gone to Church

But when the attack came, nobody would believe it.

Mrs. Moon had gone to a 7 a.m. church service and had the University of Hawaii's Episcopal Club at her home for a breakfast

meeting. This was part of her work as assistant dean of students. The meeting had begun, she remembers, when the phone

rang. It was her sister, Mrs. K.L. Butler, who lived in the neighborhood, telling her that her children had heard on the radio

that Pearl Harbor was "under enemy attack." It wasn't until later that anyone said anything about a Japanese attack, she

says.

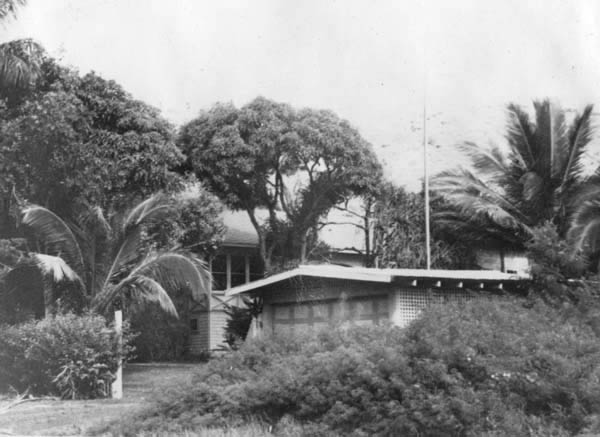

The home of Otto H. and Cenie (Simmerman) Hornung at 626 Maui Street in Honolulu where their

daughter, Cenie Hornung, lived until shortly after the 7 December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor.

"I thought it was a silly story," Mrs. Moon remembers. "I thought they'd been listening to some radio program and

mistaken what someone had said."

Mrs. Butler, it seems, didn't think so. She was afraid it was true. Mrs. Moon's father, O.H. Hornung, tuned in

his radio and heard the same thing. He urged sending the people present at the meeting to their homes immediately.

Went On With Plans

The group's president, Mrs. Moon recalls, went right on pacing up and down before the assembled group outlining proposed

arrangements for a dance the club was planning. He didn't seem to put much stock in the story."

They could hear gunfire in the distance, she says, but that didn't necessarily mean anything. The Navy had been

carrying on battle practice for some months. Everyone thought this was more of the same.

Mrs. Moon recollects that she later head of numerous high government officials, who heard the gunfire and saw the smoke

and who called high Navy officials telling them to tone down the maneuvers a bit. Things were getting too realistic, they said.

"It finally began to dawn on us just what was happening," Mrs. Moon continues. It took us a long time to realize that what

the radio said was true: an enemy power was attacking Pearl Harbor."

She remembers that the Episcopal bishop, present for the meeting, led them in prayer before members of the group left for

their homes. One projectile fell near where they had been attending church services an hour and a half before.

That was about 8:30 a.m., or about the time the biggest part of the attack came.

"We laid low for a while," Mrs. Moon relates, "as we let the idea that we were under attack sink in. Then we realized

that we didn't have any bread in the house. We thought it might be a good idea to go down the street and get some.

When we got near the store, we saw a line around the block and most of the shelves empty."

Newspaper Report

"Dad couldn't contain himself. He wanted to go downtown to look around and to get some bread. On the way we

went to see my sister, whose husband was at sea on the USS Indianapolis. We found a collection of scared Navy wives on

a hill overlooking the harbor. My sister had a newspaper that said enemy troops were landing."

"The rumors were just terrific. You heard all sorts of things about everything."

They returned home and spent the rest of the day reading "White Cliffs of Dover" to the children while calls for all military

personnel came on the radio.

"A lot of ROTC kids were handling live ammunition that day for the first time, although some of them had trained with it before,"

she comments.

"We covered everything with blankets and kept all the lights off. It's terrible when you don't know what is happening

and there's no one to ask, no way to find out."

Refugees

"The next day I went to the University and found the buildings full of Pearl Harbor refugees. My job was to organize the girls

at the University so they could help take care of the refugees." she says.

These refugees were civilian personnel evacuated from the immediate harbor area during and after the attack. Most of

them had lost everything.

"Anybody who had a car went running errands looking for anything from a toothbrush to pablum," she recalls.

The Navy evacuated most of the refugees to the U.S. within a month after Pearl Harbor. But in the meantime, she

moved into the university buildings and helped supervision of work with the refugees until they were removed to the

mainland. Mrs. Moon, who was still Miss Hornung then, stayed in the islands.

She describes her feelings during the attack and after as running the gamut of disbelief, despair, and finally a determination

to do what she could to help out with the homeless and displaced.

"There was no use in worrying about what we didn't know about. The horror of the attack began to dawn when we found how

many casualties there had been at Pearl Harbor. And more especially when we heard of friends that had been killed or wounded."

Mrs. Moon recalls she had been disturbed before the attack about the possible disloyalty of Japanese-Americans. But, she

hastens to add, these fears quickly vanished after the attack. There were many Japanese-Americans in the local National Guard

and university ROTC organizations. Soon after the attack, these units were disbanded and their membership given the

opportunity to re-enlist. But enlistments were closed to Japanese, regardless of their citizenship.

Work Gangs

But American citizens of Japanese derivation organized work gangs and offered themselves to the commanding general for whatever

service they could perform. They did all sorts of dirty jobs with no thought about pay or rank or uniforms. And when

they won permission to enlist in the regular Army, they provided the nucleus of the 412nd regiment, most decorated unit in the Army

during the war, she recalls.

She met her husband, F.R. Moon, Jr., in 1943 when he was stationed in Hawaii in the Navy. They were maried that same year and had

two children, Annie Lou, 9, and Frank Russell Moon III, 8, before Moons' return to Virginia. Their third child, Cenie Re, 3,

was born locally.

Cenie (Hornung) and Frank Russell Moon at 626 Maui Street in Honolulu shortly after their marriage in 1943.

Otto Henry and Cenie (Simmerman) Hornung lived in Hawaii during the war;

they were the parents of Cenie (Hornung) Moon.

Every Sunday after church at St. Andrews Cathedral in Honolulu during WWII,

Mrs. Otto Hornung invited servicemen back to her home at 626 Maui Street for

a home-cooked Sunday dinner. Shown in this photo are U.S. servicemen,

Mrs. Hornung, Cenie, and several of Mrs. Hornung's granddaughters.

|