Oral

Historian: Margaret A. Sells Oral

Historian: Margaret A. Sells

Interview Date: 20 August 2008

Interviewer: John McQuarrie

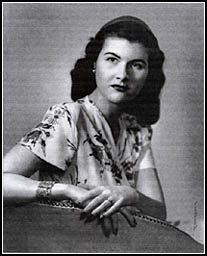

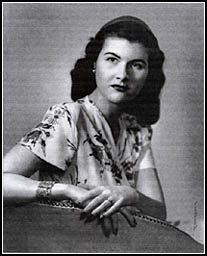

Dr. Margaret Sells Emanuelson

was born Margaret A. Sells on February 1st, 1924. She grew up in Atlanta,

Georgia. The daughter of an Army Major, who was a veteran of WWI, she

recalled a story of a time in her early childhood when she and her father

stood on a parade ground and watched the American flag being lowered to the

playing of taps. He explained to her that the men doing this were extremely

careful never to let the American flag touch the ground. Even at her young

age, she understood the importance of that concept. The surge of pride and

patriotism, she said, was something that never left her.

After completing high

school, Ms. Sells enrolled in Shorter College-then a women's college. After

two years, she transferred to the University of North Carolina, at Chapel

Hill. There, she met Bill Emanuelson, her future husband. In 1944, she

graduated at age 20-a remarkable feat, considering that so few women attended

college, at the time, let alone finished at an age two years younger than

their peers.

During Ms. Sells' time in

school, America was hard at work to win the war, but that work was well

underway even before the United States entered the war. Americans, Dr. Emanuelson

explained, were largely interested in avoiding another global conflict,

having just gotten out of one twenty years before. Conscription, which began

in 1940, coupled with a huge boom in industrialization, was America's way of

posturing ourselves to simultaneously avoid war and send aid to our allies.

The unanticipated consequence of this was that the window of opportunity for

women to participate was thrown open like never before. Ms. Sells was not the

only woman she knew who was anxious to participate. Her mother was working in

Washington, D.C., for GT, and her future mother-in-law got someone to swear

that she was two years younger than she was so that she would be eligible to

serve in the Women's Army Corps (WAC).

After leaving school, Ms.

Sells went to work in Washington, D.C., for the Bureau of Ships. Created just

before WWII, the Bureau of Ships was charged with coordinating the massive

naval fleet that ferried troops and supplies all over the world to supply our

allies and sustain the United States' foreign campaigns. Ms. Sells was hired

by the Bureau under the classification CAF, or

Clerical-Administrative-Finance. Her assignment was Code 203, which meant that

she was working in the personnel department. The Bureau of Ships worked to

coordinate the thousands of officer, enlisted, and civilian personnel that

were affiliated with the Navy and its installations. Her position allowed her

access to some information that was of particular interest to her. She had a

boyfriend on the cruiser, USS Santa Fe, and she wanted to see the plans of

the ship, which her commander allowed her to do.

In June 1944, shortly after

arriving at the Bureau, Ms. Sells requested a weekend leave to go to Virginia

Beach, VA. The Bureau's employees worked six days per week, and Ms. Sells had

not worked there long enough to accumulate time off, so she was given

permission to take a weekend trip with the caveat that she work seven days

the following week. When she returned to work, she found that both the

Secretary of the Navy and her commander, who worked for the SECNAV, were very

unhappy. Apparently, the filing system for organizing the various positions

and vacancies for the officer, enlisted, and civilian personnel had been

badly disorganized. The Bureau was struggling to get their affairs in order.

On the Sunday when Ms. Sells arrived to put in her extra time, she was given

the task of sorting out the mess. Her solution was to get a large sheet of

paper and a ruler and make a huge chart that outlined all of the various

positions and who filled them, and identified any vacancies. On Monday, she

presented her work to her commander, who subsequently took it to the SECNAV.

For her work, she was awarded a commendation and a promotion-ahead of

nineteen employees more senior than she.

Dr. Emanuelson described

working life with the Bureau of Ships. Security and secrecy were at a

premium. At the entrance to the main office on Constitution Avenue, there were

armed guards and people, who checked every bag and package that entered the

building. All over the walls there were posters with clever slogans like,

"Loose lips sink ships," and "Shhh." In a time when men

all over the country were being drafted into service, there were a great many

female officers who stepped up to work at the Bureau of Ships; the commander

for whom Ms. Sells worked was a woman.

Dr. Emanuelson paints a

very vivid picture of the patriotism that infected American youth during

WWII. It is easy to see why she was so gung-ho to work in a combat support

role during the war. She explained that for every GI on the battlefield, it

took about twenty other people working in support roles to make sure they

were equipped to carry out their mission. Absolutely everything was rationed.

Cigarettes were nearly impossible to get as they were all being sent to the

GIs, and when Ms. Sells got them, it was usually from her friends fighting

overseas. The mood was tense, but when the troops would come home on leave,

it was a huge party. "Eat, drink, and be merry for tomorrow you might

die," she said, "and sometimes you did."

In September or October

1944, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) approached Ms. Sells to work for

them. Created in 1942 as a response to the United States' desperate need for

a formal intelligence service, the OSS recruited personnel from all walks of

life. A friend of Dr. Emanuelson's, Betty McIntosh (then, Elizabeth Teet),

was recruited by the OSS after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. At the time, she

was working there as a journalist for a newspaper owned by Scripps Howard.

Singer Marlene Dietrich and the now-famous culinary genius, Julia Childs,

also worked for the OSS in the morale operations with Betty McIntosh. Ms.

Sells was never fully aware of how she was chosen for OSS, but her friends in

Atlanta later told here that FBI agents had been around asking questions

about what kind of person she was-obviously surveilling her to see if she was

a suitable candidate for the OSS.

When Ms. Sells was brought

to work for the OSS, she was subjected to extensive psychological and

situational testing. At the time, she explained, psychological testing was

beginning to emerge as a metric for a variety of things. GIs were given

pencil and paper tests to determine their suitability for combat, and

alarmingly, Dr. Emanuelson explained, nearly 60-70% of those tested were

found to be unfit for duty. Ms. Sells testing was quite different. Aside from

the exhaustive individual psychological examinations, she was also given a

battery of situational examinations. She recalled an incident where she and a

group of men were placed in a room with some chairs and boards, and they were

instructed to build a bridge over a thirty-foot expanse of water. The materials

were clearly insufficient to accomplish the task, but the point of the test

was to observe leadership skills and how the recruit interacted with others.

As a woman, Ms. Sells had trouble getting any of the men to listen to her,

but in spite of it, she was brought on board by the OSS.

Information was a carefully

guarded commodity with the OSS. Dr. Emanuelson explained how information

related to any work that went on was strictly need-to-know. People simply did

not discuss OSS-related matters with anyone to whom it did not relate, and

with very good reason. America's best and brightest were the ones selected

for OSS work, and of those, only the most fit were sent overseas. For her own

part, Ms. Sells worked in a converted warehouse somewhere in Washington, D.C.,

as she was too young for overseas service. She had a colleague in the office,

Millie, who she suspected of being there to keep an eye on her while her

application and full acceptance into the OSS was being approved.

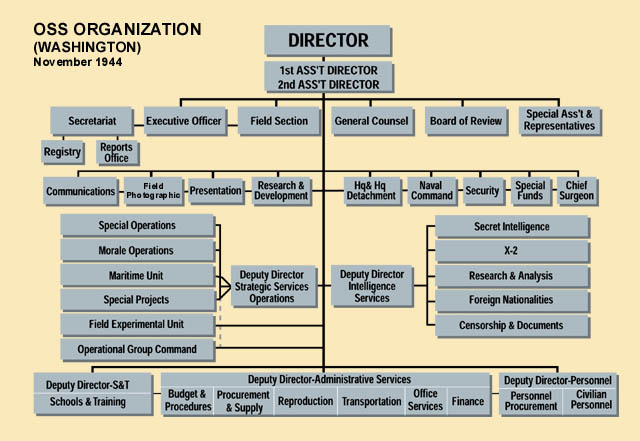

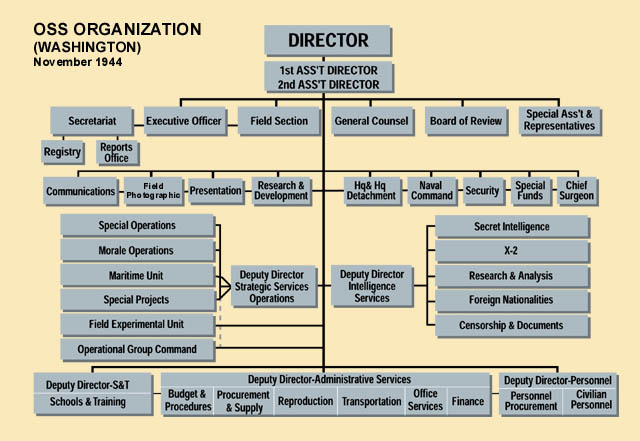

The OSS was a very broad

umbrella for a myriad of wartime activities. Within OSS, there were several

branches: secret intelligence, research and analysis (which Dr. Emanuelson

said was where agents were sent if there was no other place for them),

special operations, X-2 (which had veto power over everyone else, as they

were the big-picture people), research and development, morale operations,

maritime units, operational groups, communications, and medical services.

Because the nature of the work was so intertwined and secretive, Dr. Emanuelson

suggested that it was really very difficult to pinpoint exactly to what end

your efforts were working.

OSS Organization Chart, November 1944

The OSS and their British

counterpart, MI-6, worked very closely throughout the war, and American

agents were often sent to collaborate with the British. The British had

different operational methods that were, by comparison to the American tactic

of rigid measurement, very subjective. In more than one instance, American

operatives, who had been cleared for duty, went overseas and were rejected by

the British. In those cases, American psychologists like Dr. Emanuelson's

friend, Dr. William Morgan, had to go and calm the waters to get the

Americans into action. Later in the war, Dr. Morgan would work to coordinate

resistance groups in places like France with the OSS and

MI-6.

Dr. Emanuelson was quick to

explain that one needed not travel overseas to work as a spy. There was a

fair amount of espionage happening in Washington, D.C. In France during WWII,

the provisional Vichy government was in place. They were cooperating with the

German government, so that made them something of a threat to the United

States. A woman named Cynthia, the daughter of a prominent physician and

general, was working for the OSS at the time. She and her male partner were

assigned to break into the French embassy and photograph documents that were

kept in a safe. Cynthia seduced a young French diplomat to lure him out of

the office so her partner could retrieve the information that they were

seeking. She succeeded, and later fell in love with and married the diplomat.

Dr. Emanuelson did not know Cynthia personally, and pointed out that her

tactics, though effective in that situation, were not proscribed practice for

women in the OSS.

Dr. Emanuelson described

her time in OSS as a lot of hurrying to get someplace, and then waiting for

more to do. The State Department required that any agent who worked overseas

be at least twenty-one years old. When she went to OSS, she was twenty, and

had to wait for her birthday to be eligible for overseas travel. After her

birthday, however, she was put "on alert." To be on alert meant to

be ready to leave the country at a moment's notice. The alert period

typically lasted four weeks. As the clock ticked down, the agent could be

more and more sure that their departure was imminent. During the last week of

Ms. Sells' alert period, two or three days before her last day of alert, the

war in Europe ended.

Shortly after VE-Day, Ms.

Sells' then-boyfriend, Bill Emanuelson, was on leave from the Navy. He had been

flying overseas, and was home for ten weeks. The two decided to get married,

and Mr. and Mrs. Emanuelson both agreed that the war with Japan would soon be

over. It made little sense to take any unnecessary risks by traveling abroad,

and so Mrs. Emanuelson resigned from the OSS.

After WWII ended, Dr. Emanuelson

explained, President Truman was very concerned about the OSS in a post-war,

peacetime atmosphere. As he saw it, General Donovan, the general in charge of

the OSS, controlled a lot of information and personnel that could conceivably

operate unchecked, and present a challenge to the federal government's

authority. In October 1945, President Truman dissolved the OSS along with

other war agencies; OSS functions were transferred to the State and War Departments.

But the need for a postwar centralized intelligence system was soon

recognized in Washington, and two years later in September 1947 the Central

Intelligence Agency (CIA) was created.

Mr. and Mrs. Emanuelson

moved to Virginia Beach, VA. They purchased a home in Linkhorn Park and lived

there for several years. After one particularly devastating hurricane that

hit the area, the Emanuelsons found a large home called Greystone on nearby

Crystal Lake that had been badly damaged and vandalized after the storm. They

purchased the home, restored it, and lived there with their five children

until they moved back west, and eventually settled in Scottsville, VA.

At about the time that the Emanuelsons

moved into Greystone, Mrs. Emanuelson became Dr. Emanuelson after finishing

her doctoral work in clinical psychology at the University of Virginia. She

had previously received a Master's Degree from Virginia Commonwealth

University. Dr. Emanuelson was hired as the first Chief Psychologist for

Virginia Beach City Public Schools and virtually created the school

psychology program that exists there today. After leaving that position, she

became the Director of Psychological Services for a nearby psychiatric

hospital and started a school there for learning disabled and emotionally

disturbed children. Following that work, she spent the next thirty years in

private practice and was a very sought-after expert witness, examiner, and

consultant for numerous court cases.

Margaret Sells Emanuelson, August 2008

Today, Dr. Emanuelson is

still very involved in the in the OSS society. Her long-time friend, Betty McIntosh,

publishes the quarterly OSS Bulletin, and there is still a very active and

connected network of OSS veterans. Dr. Emanuelson herself has published two

novels that chronicle the exploits of fictional characters living out the

activities that Dr. Emanuelson and her cohorts actually did. As Dr. Emanuelson

pointed out in her interviews, the fact that men were fighting overseas made

it possible for women to get involved with agencies like the OSS, and female

operatives feature prominently in her novels. In fact, nearly one fifth of

the 25,000 OSS agents operating in WWII were women.

Even today, though OSS

veterans are still in touch, their dedication to secrecy and intelligence

gathering for the Unites States is a hard habit to break. Years ago, Dr. Emanuelson

saw her friend and former OSS colleague, Dr. Morgan, at a conference of the

Virginia Psychological Association. He asked her what work she had done

during her time in the OSS. She replied, "Not much of anything." He

laughed, and agreed that probably the most appropriate answer.

|

In an

interesting comparison, and by way of closure, Dr. Emanuelson explained

that in many ways, her career as a forensic and clinical psychologist was a

great deal like being a spy. Treating a patient is only possible if you can

first ascertain the cause of the problem. In the same way, the flexibility,

investigative techniques, and problem solving skills used in psychology are

exactly what one needs to be a spy.

|

|

|

|

|

|