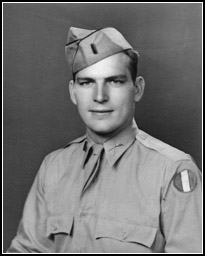

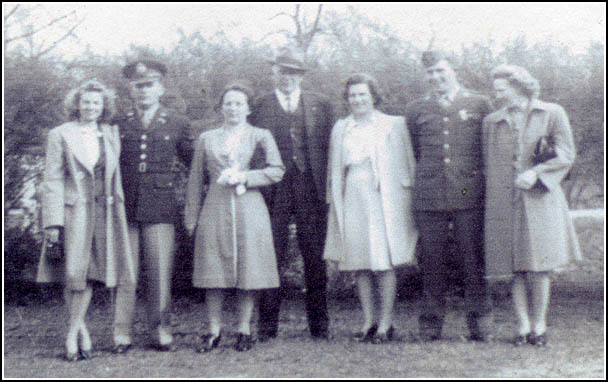

Oral Historian: Thomas J. Bugg, Jr.Date of Birth: 29 March 1920Interview Date: 23 July 2008Interviewer: John McQuarrieThomas J. Bugg, Jr. was born 29 March 1920 and spent his early years on Shores, VA (about 15 miles east of Scottsville on the James River). Then, it was a small town, and today, it does not even have a post office. In the fall of 1940, Mr. Bugg started his undergraduate studies at Virginia Polytechnic Institute (Virginia Tech) to pursue a degree in animal husbandry. On 4 August 1942, at age 22, Mr. Bugg enlisted in the Army reserve in Blacksburg, VA. At the time, the majority of the student body at VPI were members of the Corps of Cadets, and coordinately served in the military reserve. According to Mr. Bugg, life in the Army Reserve in Blacksburg consisted of little more than parade and some very limited weapons training. Mr. Bugg did, however, learn from the command structure of the Corps of Cadets and the Army Reserve, and in that way, prepared himself for life in the military. On 7 April 1943, the junior and senior classes at VPI were inducted into active duty. The senior class went right to Officer Candidate School as they had completed their degrees, but Mr. Bugg, a junior at the time, was sent to basic training at Fort McClellan, AL. There, Mr. Bugg trained further as an infantryman. He qualified as a sharpshooter with the M1 rifle and trained further with military procedure and weaponry in preparation for combat. His service record indicates that his infantry specialty was as a gunner. From Fort McClellan, Mr. Bugg shipped out by train to Ft. Benning, GA, for Infantry Officer Candidate School. He had very little to say about the training he received there, and suggested loosely that the main focus of OCS was to develop leadership skills. By reason of "convenience of the government," CPL Bugg was honorably discharged from the Twenty-First Company, Third Student Training Regiment on 11 April 1944, and immediately thereafter received his commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Army Officer Reserve Corps.  Thomas Bugg's family during WWII. (L to R): Dorothy Bugg (his wife), Thomas, Virginia and Jack Bugg

(his parents), Virginia Bugg (his sister-in-law and a nurse in WWII), Waverly Bugg (enlisted in the Army during WWII), and an unidentified woman. After received his commission 2LT Bugg transferred to Camp Robertson in Little Rock, AK, where he took command of a platoon. His duty assignment at Camp Robertson was to prepare his platoon for deployment to the European Theater of Operations (ETO). According to Mr. Bugg, training a platoon for combat consists of general physical training, weapons training, and drilling in combat tactics and maneuvers. In late June 1944, 2LT Bugg and his platoon deployed to the ETO aboard the USS Argentina. The voyage was fairly uneventful, and not at all comfortable. Bunks in the hold of the ship were stacked four high, and there was not an unused square-foot of space. The Argentina was part of a convoy of roughly sixty ships. During the early stages of WWII, German U-boats wrought untold havoc on Allied ships crossing the Atlantic. To mitigate that risk, American transport vessels-especially those carrying troops and high-value cargo-traveled in packs and under heavily armed escort. This system made spotting and defending against U-boats far easier. 2LT Bugg debarked the Argentina in England, and after a very brief stay there of only a few days, 2LT Bugg and his platoon crossed the English Channel into Normandy. They landed on Omaha Beach on 10 July 1944, just short of five weeks after the initial D-Day invasion. Mr. Bugg commented later that in that short time, the vestiges of the horrendous fighting that occurred there had already begun to disappear. To 2LT Bugg, Omaha Beach looked like any other beach, with the notable exception of the burned-out hulls of transport vessels that littered the waters nearby. Upon arriving in the ETO, 2LT Bugg and his platoon were assigned to the 119th Regiment, 30th Division. His mission was to join up with the rest of the American fighting force that was tasked with pushing the German lines back into Germany. His combat excursions took him across northern France, into Belgium, Holland, and finally, into Germany. As an Army Infantry officer working as a platoon leader, 2LT Bugg's responsibilities consisted of monitoring the training, safety, and movements of his troops. At the point in the war when 2LT Bugg entered combat, officer casualties had been so extensive that in many instances, non-commissioned officers (NCOs) like sergeants were filling platoon leader positions. Unlike in other parts of the ETO, 2LT Bugg and his men were fairly well supplied. They always had rations, and normally the supply companies traveling just behind them could supply freshly cooked meals. Along their way into Europe, 2LT Bugg and his men would sometimes find liberated families to stay and eat dinner with. Mr. Bugg recalled one family that had been liberated in Belgium. They prepared a veritable feast of rabbit and other regional delicacies for the American GIs. By the time 2LT Bugg's platoon crossed the formidable Siegfried Line, his company commander (CCO) and all but thirteen of the original thirty-seven of his original platoon had been killed in action. The final, and least fun part of an Army officer's job consists of managing personnel turnover in combat. Because of the heavy casualties sustained, there was quite a bit of that work to be done. On 6 October 1944, the rest of 2LT Bugg's platoon, including 2LT Bugg, were captured by German forces and interned at a prisoner of war camp somewhere in Bavaria. 2LT Bugg, as he was an officer, was separated from the enlisted men in his platoon and sent to a different camp. The camp to which 2LT Bugg was sent consisted mostly of downed American pilots.

As the Russian advance on the Eastern Front began squeezing German resistance out of Poland, German forces fell back to Pomorze, at the extreme western edge of Poland, adjacent to Germany. On 21 January 1945, 2LT Bugg and his compatriots were marched out of Oflag 64 on what would become a 350-mile march back into Germany. Of the roughly 1,500 men that left Oflag 64, only about 400 reached their destination.

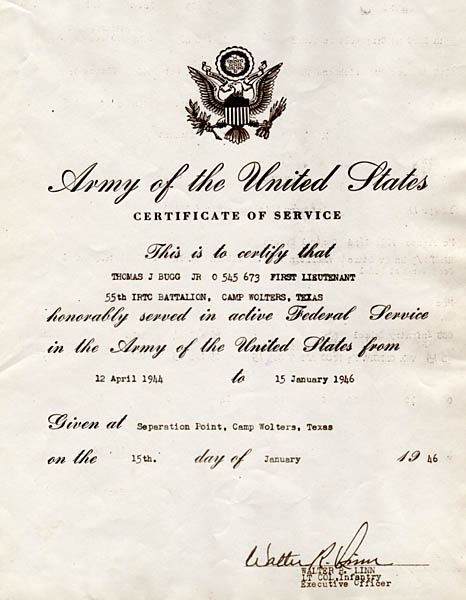

Mr. Bugg recalled having the sense that the German guards were every bit as anxious to seek refuge as their captives, and perhaps because of this, the guards treated the American POWs fairly decently. What 2LT Bugg learned, however, was that this decency was not extended to all POWs. On several occasions, the Americans would pass by Russian POWs, who were being absolutely terrorized by their Russian captors. All along the way, the POWs and guards were just miles ahead of the Russian advance on Berlin. On one night in particular, 2LT Bugg and his fellow POWs were sleeping in a barn and the Russian troops were so close that they could hear gunfire and see explosions on the horizon. The guards, fearing for their own lives, ran away and were replaced by a group of SS. For the duration of his time in captivity, 2LT Bugg was treated well by his captors, but they constantly warned the POWs that if the SS were around, they should be very cautious and obedient. In this instance, when the SS arrived, they quickly roused the POWs to begin marching out of the area. Some of the POWs tried to hide by burying themselves in some hay in the barn. After the brief grace period that the SS had offered the POWs to evacuate the barn, they began firing into the hay to take care of any escapees. Finally, 2LT Bugg arrived at the POW camp Stalag VII-A in Moosburg, Germany. In the last few days of April, the guards overseeing 2LT Bugg and his fellow POWs had left, and on 28 April 1945, American troops liberated the camp and delivered the news that war was finally over. Just nine short days later, 2LT Bugg and his compatriots in the ETO were able to celebrate VE-Day, the day the Western Axis Powers surrendered to the Allies. Mr. Bugg told a funny story about his acclimation from POW life to life as a liberated American soldier. His whole life, Mr. Bugg never cared for sunny-side-up eggs or sweet milk. At one point during his captivity, he was particularly struck by hunger pains and decided then and there that whatever was put in front of him for the rest of his life, no matter what it was, he would eat. Surely enough, after being liberated, 2LT Bugg ended up in an American camp where items on the menu for breakfast were sunny-side-up eggs and sweet milk. Considering his options and recalling the promise he made to himself, 2LT Bugg decided that the freedoms he had been fighting to protect meant that as a free man, he was free from having to eat anything he did not want to eat. Although it seldom happened in WWII, 2LT Bugg left Europe aboard the same ship that had taken him there, the Argentina. 2LT Bugg debarked in North Carolina, where he remained for two weeks in a rest and recovery hospital until he was ready to return to duty. In late August 1945, 1LT Bugg (who had been promoted at an unknown point during his time as a POW) arrived in Camp Wolters, TX to begin his duty assignment as a company commander. During his hospital stay in North Carolina, Japan surrendered, and WWII was effectively at an end. All that remained for 1LT Bugg to do was oversee the dismantling and deactivation of his company. That job required accounting for every single piece of government property that had been issued to that company. 1LT Bugg was more than a little concerned that this would not happen, and that he would be help personally responsible for every missing item. Fortunately, his account of where everything had gone was sufficient, and 1LT Bugg was Honorably Discharged from the Army of the United States on 15 January 1946. Over the course of his service, 1LT Bugg was awarded the Good Conduct Medal, Combat Infantryman Badge, European-Africa-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal, World War Two Victory Medal, American Campaign Medal, Bronze Star, Prisoner of War Medal, and American Defense Service Medal.  Thomas Bugg's separation papers from the U.S. Army, 15 January 1946

Mr. Bugg said of his service that he was extremely proud to have served, but he was equally glad to get out. After his discharge, Mr. Bugg took advantage of the GI Bill and returned to VPI to finish his degree in animal husbandry. Back at school, Mr. Bugg found that his college roommate prior to WWII, Lloyd Riggle, had been killed in action. All three of the company commanders under whom he had served in the Army Reserve at VPI had also been killed. All told, 312 VPI students, past and present, had been killed in action during WWII. Upon leaving school, Mr. Bugg went to work as an Agricultural Extension Agent. In 1914, the Smith-Lever Act created a program whereby land-grant universities would send out agents to educate rural farmers and families about new developments in the science of agriculture. In Virginia, the major land-grant university was, and is, VPI. Mr. Bugg's work as an extension agent brought him to Fluvanna County. Although he quit his job as an extension agent after one year, Mr. Bugg remained in Fluvanna as a farmer and still lives there today. During the time that Mr. Bugg has lived in Fluvanna, he was elected to a position on the Board of Supervisors, and was subsequently appointed to serve on the Jail Board, which he did for fifteen years (a somewhat fitting placement for a former POW).

|